It was an issue that united Bernie Sanders on the left and Donald Trump on the right: opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

A man calling himself “The Death of US Jobs” joins thousands of other people as they attend the “Not To This NAFTA” rally on the steps of the state capitol in Lansing, Michigan, September 18, 1993.Lennox McLendon/AP

It’s one reason Trump won the White House, amid populist calls for protectionism. Many blue-collar workers in traditionally manufacturing-heavy states like Michigan blamed the trade deal for job losses, declining wages, and companies shifting manufacturing to Mexico.

President Trump, in particular, made the debate over free trade one of the central topics of his campaign. He argued in favor of ripping up trade deals, said NAFTA was “the worst trade deal in the history of the country,” and called the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, “a rape of our country.”

During his first week in office, Trump signed an executive regarding his intent to pull the US out of the TTP. Additionally, he has on multiple occasions stated his intent to “renegotiate” NAFTA.

With its future in doubt, following is a guide to everything NAFTA — past, present, and future.

What is NAFTA?

The North American Free Trade Agreement is a trade deal between the US, Mexico, and Canada. It was negotiated under President George H. W. Bush and implemented under President Bill Clinton in 1994 after heated debate in Congress.

NAFTA eliminated most tariffs, such as taxes on imports and exports, and on traded goods among the three nations. It put in place processes to get rid of other trade barriers too. The agreement followed the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement, which was implemented in 1989 and aimed to eliminate trade barriers between the two nations.

NAFTA — and other trade agreements such as TPP — should not be conflated with trade in general. Trade, in its simplest definition, is the exchange of goods or services between entities. Trade agreements like NAFTA and TPP establish legal frameworks to ease the flow of goods and services across national borders. As we will see below, this has positive and negative consequences.

What was NAFTA intended to do?

President Clinton holds an apple while attending a North American Free Trade Agreement trade fair on the South Lawn of the White House, 1993.Joe Marquette/AP

The point of NAFTA was to encourage economic integration among the US, Mexico, and Canada. And that, by extension, was supposed to boost economic prosperity for all three.

Trade between countries can theoretically improve economic efficiency and make everyone wealthier by allowing countries to specialize in what they’re good at.

For example, if the US can grow corn more efficiently than Mexico, and Mexico can build cars more efficiently than the US, then it makes more sense for the US to grow a lot of corn and Mexico to build a lot of cars, and then for both countries to trade cars for corn with each other, rather than for each country to less efficiently do both things on its own.

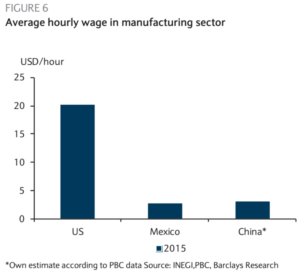

More concretely, one effect of increased economic integration would be for US firms to move production over to Mexico where labor is cheaper than in the US or Canada — for example, with the auto industry.

Ahead of the deal’s implementation, President Clinton argued that, in the longer-term view, NAFTA was also about the US adapting to the changing technological and economic landscape.

“In a fundamental sense, this debate about NAFTA is a debate about whether we will embrace these changes and create the jobs of tomorrow, or try to resist these changes, hoping we can preserve the economic structures of yesterday,” he said at the signing ceremony for the supplemental agreements to NAFTA on September 14, 1993.

He continued in the speech:

“I tell you, my fellow Americans, that if we learned anything from the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the governments in Eastern Europe, even a totally controlled society cannot resist the winds of change that economics and technology and information flow have imposed in this world of ours. That is not an option. Our only realistic option is to embrace these changes and create the jobs of tomorrow. […]

Together, the efforts of two administrations now have created a trade agreement that moves beyond the traditional notions of free trade, seeking to ensure trade that pulls everybody up instead of dragging some down while others go up. […] This agreement will create jobs, thanks to trade with our neighbors. That’s reason enough to support it.”

In retrospect, it’s notable that Clinton’s proposed solution to the “changes” happening in economics and technology in the early 1990s — that is, “to embrace these changes and create the jobs of tomorrow” — is virtually the opposite of Trump’s proposed solution to economic and technological challenges of 2016 (“to Make America Great Again” by trying to go back to the old-school manufacturing jobs.)

Is there any point to NAFTA aside from the economics and jobs angle?

At least to some degree, free-trade deals are not just about the economic benefits for your own country, but are also about fostering positive relations with the other country. Or, as some economics professors like to say, “When goods don’t pass international borders, soldiers will.”

With respect to NAFTA, The Wall Street Journal explained it as such:

“NAFTA advocates say the economic debate misses the bigger point of the deal, which has been to ameliorate longstanding tensions across the border and turn Mexico into a more steadfast US ally. By that standard, they say, the pact has been a great success, fostering more bilateral cooperation on issues from crime to the environment—and keeping Mexico from following the path of left-wing Latin American countries or drifting closer to American rivals like China.”

On a related note, analysts had argued that TPP was largely about geopolitical benefits — namely, the US’s position in Asia.

What happened to American workers after NAFTA was signed?

Debbie Kellogg, right, a school teacher, and Russ Leavitt, a UAW employee, express their opinion of the proposed North American Free Trade Agreement while heading to a rally with House Majority Leader Rep. Richard Gephardt, 1993, in St. Louis.James Finley/AP

Some believe NAFTA has hurt US workers, and there is empirical evidence to back up these grievances.

In 2016, economists Shushanik Hakobyan and John McLaren explored NAFTA’s effect on the US labor market by looking at wage growth among employed workers and comparing census data from 1990 to 2000 — the census before NAFTA took effect and the one after.

They found mixed effects on the US labor force. Although for the average worker there wasn’t too much of a difference, a concentrated minority saw a significant decrease in wage growth that could be correlated with NAFTA. Blue-collar workers were more likely to be affected, college-educated workers were less so, and executives saw some benefits.

“The most affected workers were college dropouts working in industries that depended heavily on tariff protections in place prior to NAFTA. These workers saw wage growth drop by as much as 17 percentage points relative to wage growth in unaffected industries,” McLaren said in an interview with UVA Today.

“If you were a blue-collar worker at the end of the ’90s and your wages are 17% lower than they could have been, that could be a disaster for your family.”

McLaren said that it wasn’t just the industries that were affected but entire towns that depended on those industries: Factory towns have grocery stores, bowling alleys, and public schools that all rely on industrial workers as customers. The example McLaren gave was this: “A waitress working in a town that depends heavily on apparel manufacturing might miss out on wage growth, even though she does not work in an industry directly affected by trade.”

Ultimately, he notes that, yes, there is evidence to support that for some American workers, wages were hurt by NAFTA. However, at the same time, these figures should not be exaggerated.

“I think it is important to get the information on the table and to show that there do appear to be blue-collar workers whose incomes have been reduced by this trade agreement,” he told UVA Today. “At the same time, I think it is important to use data to prevent those claims from being exaggerated. Some commentators throw around claims that millions of jobs were destroyed by NAFTA, which I don’t think are supported by the evidence.”

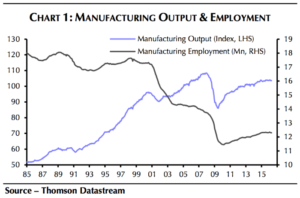

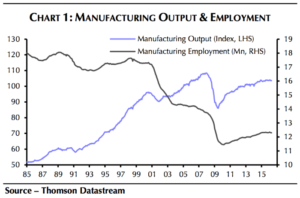

Did manufacturing employment start falling only after NAFTA?

No. The decline in American manufacturing employment predates NAFTA, as you can see in the annotated chart below. In other words, NAFTA alone is not responsible for the loss of US manufacturing jobs.

Additionally, it’s notable that a big drop-off in manufacturing jobs correlates with the economic shock of China joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. And, the steepest decline occurs after the financial and housing crisis in 2007-08.

Image: http://static6.businessinsider.com/image/588f7e81713ba1bb008b5703-1200

Some empirical evidence suggests China’s emergence affected US wages and jobs, too.

Back in January 2016, economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson published a paper showing:

“Adjustment in local labor markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences. …

“Exposed workers experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income. At the national level, employment has fallen in U.S. industries more exposed to import competition, as expected, but offsetting employment gains in other industries have yet to materialize.”

Additionally, although Trump has fixated on the US trade deficit with Mexico, it’s notable that it is far smaller than the US trade deficit with China. Both deficits are highlighted in red below.

Image: http://static5.businessinsider.com/image/588fa1f94757520b128b5597-840/screen%20shot%202017-01-30%20at%2032727%20pm.png. Barclays.

Has trade been the only factor correlated with manufacturing job losses?

No. Automation has also played a role.

A couple of months back, Capital Economics’ Andrew Hunter shared a chart in a note to clients comparing manufacturing output (purple line) to manufacturing employment (black line).

Although manufacturing employment has been trickling downward since the mid-1980s, manufacturing output has been increasing and is now near its pre-financial crisis high. In other words, firms have been able to increase output overall with fewer workers over the years, which is likely at least partially due to automation.

Image: http://static3.businessinsider.com/image/588f8d46713ba1632e8b52f5-700/screen%20shot%202017-01-30%20at%2020004%20pm.png. Capital Economics

“It’s true that many of the manufacturing sectors that account for the bulk of the jobs lost over the past 15 years are also the ones subjected to the most competition from Chinese exports. But US manufacturing has also experienced high productivity growth, with the computers and electronics industry, which has lost the most jobs, seeing the fastest productivity growth of all,” wrote Hunter.

Moreover, it’s worth noting that manufacturing as a share of nonfarm employees has been on the decline since the 1970s — before NAFTA, China joining the WTO, and the Great Recession.

The takeaway here is that reversing the downward trend in manufacturing jobs is going to be incredibly difficult.

Image: http://www.businessinsider.com/what-is-nafta-is-it-good-for-america-2017-2 . Andy Kiersz/Business Insider

What were the positives from NAFTA for the US?

Trade among the NAFTA partners increased from about $290 billion in 1993 to over $1 trillion by 2016, according to data cited by the Council on Foreign Relations. Moreover, Canada and Mexico are the two largest destinations for US exports, making up over a third of the total.

Additionally, NAFTA has been credited with helping the US auto sector become globally competitive due to the cross-border supply chains. And American farmers have benefitted from NAFTA: Since the agreement’s implementation, US agricultural exports have nearly doubled to Mexico, and have increased by about 44% to Canada, according to the Office of the US Trade Representative.

How did American voters feel about trade deals leading up to the US election?

A Pew Research Center survey published in March 2016 found that Democratic and Democratic-leaning respondents had a more positive view of free trade agreements (60% good thing vs. 30% bad thing) while Republican and Republican-leaning respondents had a more negative view (40% good thing vs. 52% bad thing).

More strikingly, however, was the data within the bloc of Republican voters. From Pew:

“67% of Trump supporters say free trade agreements have been a bad thing for the U.S., while just 27% say they have been a good thing. Republican supporters of Ted Cruz (48% good thing vs. 40% bad thing) and John Kasich (44% good thing vs. 46% bad thing) hold more mixed views. […]

“[C]riticism of trade deals in general is particularly strong among Republican and Republican-leaning supporters of GOP presidential contender Donald Trump who are registered voters. Americans ages 65 and older and men, especially white men, stand out among this group.”

Supporters watch as Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump speaks onstage during a campaign rally in Akron, Ohio, 2016.Carlo Allegri/Reuters

“Given persistent trade deficits that have contributed to long-term wage stagnation, along with corporate capture and the absence of consumer, labor, and environmental voices at the trade-negotiating table, perhaps it’s not so crazy that these trade deals have become code for a lot of other stuff that’s gone wrong for many in the working class,” Jared Bernstein, senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and former Chief Economist and economic adviser to Vice President Joe Biden, argued in a blog post.

He also emphasized that it’s important to note that trade deals should not be conflated with trade in general, despite the fact that voters and politicians often do.

“From a political perspective, I don’t think the focus on trade is misplaced. It’s effective because it has an ‘other.’ It has a competitor or an enemy. People can picture this,” Alexander Kazan, a strategist at Eurasia Group, said in a video for the Eurasia Group Foundation. “When you talk about technology, it’s much more amorphous. It’s this sense that we all lose. So I think politically it’s less effective.”

Will NAFTA be torn apart?

The Trump administration states on the White House website that it is “committed to renegotiating NAFTA. If our partners refuse a renegotiation that gives American workers a fair deal, then the President will give notice of the United States’ intent to withdraw from NAFTA.”

At the same time, NAFTA has “created a complex integration between Mexico and the US that would be difficult and costly to break,” Barclays’ Marco Oviedo and Nestor Rodriguez wrote in a note to clients in January.

They continued in greater detail (emphasis added):

“After 22 years of this free-trade agreement, the Mexico-US trade relationship, particularly in manufacturing, has become very integrated. In fact, it is estimated that Mexico’s exports to the US comprise 40% of US value added, the largest fraction among similar economies (China is 4.2%, Canada, 25%). In that sense, separating both manufacturing sectors seems highly costly and as difficult as trying to separate the yolk from a scrambled egg. If the US were to leave NAFTA, Mexican exports to the US would face the tariffs set by the WTO, which are rather low (2.5%). However, tariffs applied to exports from the US and Canada would be higher (close to 10%). In this scenario, Mexico could choose unilaterally to reduce tariffs on its imports of US goods to avoid a disruption in trade, given its low labor costs and access to other markets.”

Oviedo and Rodriguez argue that it’s more likely that the agreement will be “renegotiated,” although there are few specifics as of this writing.

“[I]t is unclear what aspects can be modernized or if the administration plans to impose technical restrictions, differentiated tariffs or other forms of protectionism,” the duo added in their note. “Any negotiations would likely be long and could take up Donald Trump’s entire term in office (the NAFTA negotiations took five years).”

What if NAFTA is scrapped? Then what?

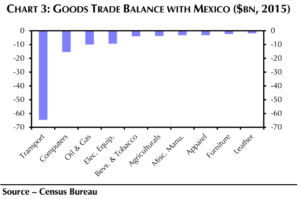

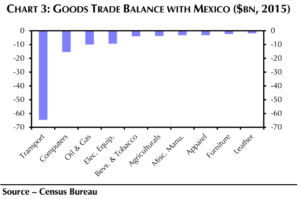

The trade deficit with Mexico is primarily driven by transportation equipment followed by computer and electronic products, according to figures from 2015, which you can see below.

Tariffs or other measures to restrict trade within the NAFTA countries could adversely affect US firms in these sectors, according to Andrew Hunter, US economist at Capital Economics.

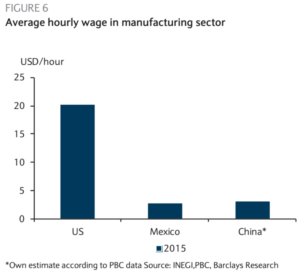

“The foreign subsidiaries of US automakers have more than $15 billion of plant, property, and equipment in the two countries. Efforts by Trump to force companies to shift production back to the US, where labor costs are higher […] could seriously damage their competitiveness relative to foreign producers,” he wrote in a note to clients.

http://static4.businessinsider.com/image/5890ea0f475752d75b8b523b-937/screen%20shot%202017-01-31%20at%2024816%20pm.png. Capital Economics

What does NAFTA mean for stocks?

On January 27, Trump tweeted: “Mexico has taken advantage of the US for long enough. Massive trade deficits [and] little help on the very weak border must change, NOW!”

Not everyone agrees with that characterization.

“Mexico may run a large trade surplus with the US, but the idea that it has ‘taken advantage’ of its large neighbor […] is surely wide off the mark,” wrote Capital Economics’ John Higgins in a note to clients.

Image: http://static1.businessinsider.com/image/5890e29f713ba1e81c8b58f9-822/screen%20shot%202017-01-31%20at%2021624%20pm.png. Barclays

“Arguably, the opposite is true, which is why his policies pose a serious threat to the earnings of the companies that dominate the S&P 500.”

US multinationals, which make up a big chunk of the S&P 500, have moved operations into Mexico since the implementation of NAFTA at least in part to keep production costs down (via cheaper labor costs there) in order to stay competitive in the global market. Lower labor costs have then boosted profitability, after which share prices have risen.

“Unwinding this process — whether in Mexico or elsewhere — might bring back some jobs to the US. But goods would be more expensive to produce with US labor than with foreign labor. And the cost of labor in the US would probably rise, given that there is no longer much unemployment in the economy,” wrote Higgins. “The pain for US [multinational enterprises] could conceivably be eased by tax cuts, but at the expense of a bigger fiscal deficit.”

“The S&P 500 has benefited tremendously from globalization. Donald Trump should be careful what he wishes for.”