Categoría: impuestos

“Si el sexo fuera un deporte, tendría muchas medallas de oro”: la vida en un burdel de Estados Unidos cuyo futuro se decidirá en las próximas elecciones

Un letrero luminoso parpadea sobre la barra del local, débilmente iluminado. Algunas chicas en lencería o ligeramente vestidas están sentadas en sofás de terciopelo con computadoras portátiles y teléfonos.

Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/660/cpsprodpb/C989/production/_103539515_976xbunny-bar-at-bunny-ranc.jpg

Air Force Amy camina alrededor de la piscina sobre sus zapatos de tacón para mostrarme el gimnasio donde las mujeres pueden ejercitarse entre los clientes. Señala el patio para barbacoas y el jacuzzi antes de abrir la puerta de un garaje en el que había algunos cuatriciclos polvorientos.

“Tenemos todo lo que necesitamos aquí, incluso ponis en el establo de atrás”, dice. “Yo no monto porque es muy arriesgado. Necesito mi cuerpo para trabajar”, agrega entre risas.

Estamos en el burdel Bunny Ranch (Rancho Conejito), el más famoso de los 21 burdeles legales esparcidos en las zonas rurales del estado de Nevada, en Estados Unidos. Los burdeles son legales en Nevada desde 1971, pero en uno de los 16 condados del estado esto podría estar a punto de cambiar.

El Bunny Ranch es el burdel más famoso de los 21 legales esparcidos por la Nevada rural. Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/624/cpsprodpb/F099/production/_103539516_976ximg_5670.jpg

El Bunny Ranch está ubicado en medio de un paisaje de arbustos salpicado de estaciones de servicio, casinos y tiendas de armas. Se encuentra justo dentro de la línea del condado de Lyon. La prostitución está prohibida en la cercana Carson City, la capital del estado de Nevada, y otras áreas urbanas.

Coincidiendo con las elecciones de medio término en Estados Unidos, el próximo 6 de noviembre, los votantes del condado de Lyon también tendrán que decidir si ponen fin o no a los burdeles legales.

“Me encanta mi trabajo”

Detrás del bar hay un pasillo, que lleva a docenas de habitaciones, cada una ocupada por una trabajadora sexual a cambio de una renta diaria.

Cuando un cliente toca el timbre de la puerta, una campana interna convoca a las trabajadoras sexuales a la recepción. Cuando el cliente elige a una de las mujeres, ella se lo lleva a su habitación a negociar un precio. La inmensa mayoría de los clientes son hombres, aunque ocasionalmente llega alguna pareja.

Air Force Amy aún es, a sus 53 años, una de las mujeres que más ganan en el burdel -dice que recauda alrededor de medio millón de dólares al año-. Las paredes están decoradas con fotos de ella en su juventud.

Con su cabello rubio platino, su cintura de avispa y sus uñas rojas brillantes, parece la estrella de una telenovela de los años 80. Pero su conversación alegre también me recuerda a la sex symbol del Hollywood de los años 30, Mae West.

“Si el sexo fuera un deporte, tendría muchas medallas de oro”, dice Air Force Amy. “Nací con este talento y me encanta mi trabajo. ¡Veo a todos esos hombres, pasamos un buen rato, me dan dinero y se llevan su ropa sucia a casa con ellos!”

Admite que no tiene algo parecido a una vida hogareña. “¿Para qué casarme y hacer a un hombre miserable cuando puedo hacer felices a miles?”, se ríe.

Su falta de entusiasmo por una vida familiar es comprensible. Criada en el Ohio rural, Amy se describe a sí misma como una “niña salvaje” que dejó su casa a los 13 años. Les permitía a los niños en la escuela que le bajaran las pantaletas a cambio de dinero para el almuerzo.

Dice que ahora puede detectar a un cliente que está borracho o es peligroso porque, como adolescente fugitiva, aprendió por la vía difícil: vendiendo sexo en la carretera para sobrevivir.

“Si el sexo fuera un deporte, tendría muchas medallas de oro”, dice Air Force Amy. Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/624/cpsprodpb/117A9/production/_103539517_976x20141103-143755-327-edi.jpg

Y, sin embargo, Amy terminó haciendo un buen trabajo con la Fuerza Aérea de Estados Unidos. A finales de la década de 1980, ella estaba en Filipinas enseñando a los militares cómo defender una pista de aterrizaje en la jungla.

Amy cuenta que pasó por algunas experiencias angustiosas en Asia que la dejaron con un trastorno de estrés postraumático y un problema con la bebida.

Cuando regresó a EE.UU., dejó la Fuerza Aérea y empezó a trabajar en burdeles donde las mujeres tenían prohibido abandonar el lugar durante un turno de tres semanas.

Finalmente, Amy se encontró con Dennis Hof, propietario de Bunny Ranch, quien la invitó a trabajar para él.

Él dice que las mujeres en sus establecimientos son libres de ir y venir y no se refiere a ellas como empleadas; prefiere llamarlas “contratistas independientes”.

“Una industria vibrante y moderna”

Hof posee un tercio de todos los burdeles legales de Nevada, y cuatro de ellos en el condado de Lyon. Para él, las mujeres como Amy son la cara exitosa de una industria vibrante y moderna.

“Este es un negocio sucio, repugnante y lleno de drogas, hasta que lo legalizas”, dice Dennis Hof, el magnate de los burdeles. Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/624/cpsprodpb/10C32/production/_103385686_976xdennis-hof-with-two-sex.jpg

“Estas chicas son mujeres de negocios, somos socios“, dice Hoff, sentado en el burdel con su brazo rodeando la cintura de otra de las trabajadoras sexuales. Ella, conocida entre los clientes como Honey, tiene alrededor de 20 años; la edad de Amy cuando comenzó hace casi tres décadas.

“Trabajos juntos”, agrega él. “Este es un negocio sucio, repugnante y lleno de drogas, hasta que lo legalizas”.

Hof llevó la industria de los burdeles al siglo XXI, con un toque del glamur de Hollywood y marketing inteligente.

Al igual que en una oficina o concesionario de automóviles, los nombres de lasempleadas del mes se muestran en una cinta electrónica dispuesta en la pared. Algunas son elogiadas y reciben obsequios, desde artículos de tocador hasta artilugios electrónicos, para asegurar la mayor cantidad de reservas.

El ambiente es mitad conferencia de ventas, mitad comuna de New Age. Las mujeres tienen que hacer declaraciones positivas como: “Trata de ser un arcoíris en la nube de alguien”.

Hof constantemente las insta a utilizar las redes sociales para atraer a más clientes. “Las chicas que publican, le sacan el máximo provecho, es un hecho”, les dice.

De lo que ganan las mujeres, la mitad se queda en la casa. Y como se jacta en su autobiografía, “The Art of the Pimp”, Hof se ha beneficiado ampliamente.

Exterior del burdel Bunny Ranch. Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/624/cpsprodpb/18162/production/_103385689_976xhi047637124.jpg

Sin embargo, argumenta que los burdeles legales benefician a todo el mundo.

“La gente necesita entender que si yo soy propietario de cuatro restaurantes McDonald’s en este condado, pagaría US$1.200 al año en impuestos (…) Si tengo cuatro burdeles, pago medio millón de dólares al año en impuestos. Ese es mucho dinero para un condado pequeño”.

Afirma que su negocio contribuye con otros US$10 millones al año a la economía local mediante el empleo de camareros, cocineros, conductores, médicos, peluqueros y otros, y dice que la industria del sexo impulsa el turismo en todo el estado.

Efectivamente, en nuestra primera mañana en el Bunny Ranch, tres hombres equipados como motoristas tocan al timbre. Son turistas de la provincia china de Sichuan, a más de 11.000 km de distancia. “Mis amigos oyeron hablar de este lugar y no podían creer que fuera legal”, dice uno. “Vinimos a verificarlo”.

“Son esclavas”

Sin embargo, si el turismo de este tipo está o no en el interés de Nevada es un debate candente.

Algunos argumentan que los burdeles hacen que todas las mujeres que viven en las cercanías sean más vulnerables a los ataques, aumentan el peligro del tráfico sexual y disuaden a las empresas respetables de invertir en el área.

Pero hasta el momento, los burdeles no parecen haber detenido el desarrollo económico en el norte de Nevada. Tesla construyó recientemente su fábrica de baterías de litio, Gigafactory, a unos pocos kilómetros de un burdel legal en el vecino condado de Storey.

Pero los críticos argumentan que más industrias de alta tecnología llegarían si los burdeles no existieran, y que aquí es donde radica el futuro de Nevada. También tienen objeciones éticas.

Brenda Simpson, del Comité de Acción Política para el fin de la trata y la prostitución, dice que es hora de dejar de mirar hacia otro lado.

La activista Brenda Simpson piensa que las mujeres que trabajan en burdeles son “esclavas”. Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/624/cpsprodpb/4CCA/production/_103385691_976xbrendaimg_5610.jpg

“Antes se consideraba correcto traer esclavos de África”, dice Simpson en el parque frente al congreso estatal en Carson City. “Y finalmente, alguien tuvo el valor de decir: ‘No, no vamos a tener esclavitud’. Este solo es otro tipo de esclavitud. Estas mujeres en los burdeles legales son esclavas”.

Activistas como Simpson quieren terminar con el trabajo sexual legal en todo el estado. El condado de Lyon fue el único de los 16 condados en el que suficientes residentes firmaron una petición para incluir el cierre de burdeles en la boleta electoral en las elecciones de noviembre.

Si la votación es exitosa, ella cree que otros condados probablemente seguirán el ejemplo.

Su grupo lanzó una reciente campaña llamada “Cerrar el mercado de la carne”. Carteles, folletos y anuncios de televisión muestran a mujeres empacadas en recipientes con envoltura de plástico, como trozos de pollo o cordero.

Melissa Holland, quien dirige un refugio para mujeres que sufrieron abusos en la cercana ciudad de Reno, tampoco compra la imagen de la “prostituta feliz”.

Dice que su organización, Awaken, ayudó a muchas mujeres en todo el estado a dejar la prostitución y encontrar otro trabajo.

Cita un estudio de la industria del sexo de Nevada realizado por un académico californiano que concluye que la prostitución legalizada mejora las condiciones para los proxenetas y los propietarios de burdeles, en lugar de para las mujeres que trabajan allí.

Y denuncia una atmósfera casi de culto en muchos burdeles legales, lo que impide que las empleadas hablen con franqueza sobre los peligros que enfrentan, incluidas las drogas y la agresión sexual.

Melissa Holland no compra la imagen de “prostituta feliz”. Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/624/cpsprodpb/5698/production/_103386122_976xmelissaimg_3153.jpg

Ninguna de la mujeres que trabajan actualmente en el Bunny Ranch me dijo nada malo sobre su jefe o sus condiciones de trabajo. Air Force Amy asegura que no se siente explotada.

“También gané mucho dinero. No podría haber ganado tanto en la calle y me siento mucho más segura”, dice, señalando el botón de pánico en la pared de su habitación, decorada con cojines plateados brillantes.

Sin embargo, siguiendo el consejo de Melissa Holland, me acerqué a algunas extrabajadoras del burdel.

Durante los dos últimos años, Jennifer O’Kane ha estado diciéndole a cualquiera que escuche que fue violada por Hof. Ella alega que el ataque tuvo lugar en 2011 cuando comenzó a trabajar en su burdel Love Ranch, en el condado de Nye, a un par de horas de Las Vegas.

“Me agarró por el cuello y dijo ‘ahora eres mía’… todo lo que podía hacer era llorar y le supliqué que parara”, me cuenta.

Jennifer dice que cuando fue por primera vez a la policía, no le tomaron una declaración adecuada y no se asignó ningún número a su caso. Hace dos años, acudió a una reunión de funcionarios del condado de Nye e intentó escalar sus acusaciones contra Hof, pero fue silenciada.

Carrera política

Al teléfono, Hof niega rotundamente la versión de los hechos de O’Kane. “Esta es una empleada descontenta que despedimos. No es verdad”, dice, calificando sus acusaciones de “absurdas”.

“De todos modos no era el tipo de chicas con las que me acuesto”, agrega antes de colgar abruptamente.

El 5 de septiembre se anunció que el magnate de los burdeles está siendo investigado por presunta agresión sexual por el Departamento de Seguridad Pública de Nevada, aunque no está claro si esto está relacionado con las acusaciones de O’Kane o con las acusaciones hechas en 2005 y 2009 por otras dos extrabajadoras sexuales de los burdeles de Hof.

Hof se presenta a las elecciones para la Asamblea Estatal. Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/624/cpsprodpb/140F8/production/_103386128_976xhof-campaign-poster.jpg

Hof dice que esas acusaciones también carecen de fundamento: él cree que está siendo atacado porque tuvo “el valor” para presentarse a las elecciones para la Asamblea Estatal en el distrito 36, en Pahrump, a las afueras de Las Vegas. Después de ganar las primarias republicanas, comenzó a llamarse a sí mismo “el Trump de Pahrump”.

“Esta iniciativa electoral para cerrar mis negocios y falsas acusaciones de ‘agresión sexual’ son obra de mis oponentes políticos”, me dice. “Lo que pensaron fue: ‘Si le atacamos, intentamos quitarle su negocio, él renunciará’. Bueno, no funcionó. Me hizo más fuerte. Y las elecciones de noviembre van a ser pan comido para mí”.

Mientras, Amy apoya a su jefe tuiteando sobre la jornada de puertas abiertas del burdel para la comunidad.

Air Force Amy con los los ponis en el establo detrás del burdel donde trabaja. Imagen: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/624/cpsprodpb/6FF2/production/_103385682_976xamyhorseimg_3144.jpg

Mientras da manzanas a los ponis en su corral detrás del rancho, parece estar reflexiva. Le digo que leí una entrevista con ella en 2001 en la que decía que iba a dejar la prostitución dentro de un año, porque estaba haciendo mella en su cuerpo y sus “articulaciones dolían como las de un jugador de fútbol americano”.

Tenía un plan para ahorrar y abrir una agencia inmobiliaria. Entonces, ¿qué pasó?

“No quiero una nueva carrera después de esta”, dice. “Esto es todo. Lo que me gusta es hacer feliz a la gente y romper las barreras de sus problemas sexuales, ¿qué hay de malo en eso?”

Amy dice que no está lista para tirar la toalla.

“Seguiré trabajando aquí mientras pueda caminar… ¡y, aunque no pueda; tal vez seré la primera prostituta en silla de ruedas! ¡Les garantizo que construirán rampas en este lugar para mí!”

Pero en noviembre, es posible que Amy no tenga otra opción. Su futuro depende de si los electores del condado de Lyon votan para cerrar los burdeles o mantenerlos abiertos.

En: bbc

Gomillion v. Lightfoot

Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U.S. 339

Supreme Court of the United States

1960

MR. JUSTICE FRANKFURTER delivered the opinion of the Court.

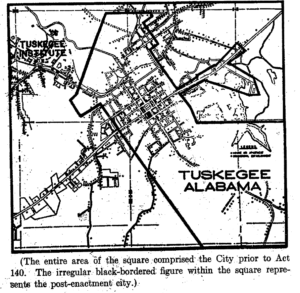

This litigation challenges the validity, under the United States Constitution, of Local Act No. 140, passed by the Legislature of Alabama in 1957, redefining the boundaries of the City of Tuskegee. Petitioners, Negro citizens of Alabama who were, at the time of this redistricting measure, residents of the City of Tuskegee, brought an action in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama for a declaratory judgment that Act 140 is unconstitutional, and for an injunction to restrain the Mayor and officers of Tuskegee and the officials of Macon County, Alabama, from enforcing the Act against them and other Negroes similarly situated. Petitioners’ claim is that enforcement of the statute, which alters the shape of Tuskegee from a square to an uncouth twenty-eight-sided figure, will constitute a discrimination against them in violation of the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and will deny them the right to vote in defiance of the Fifteenth Amendment.

The respondents moved for dismissal of the action for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted and for lack of jurisdiction of the District Court.

The court granted the motion, stating, “This Court has no control over, no supervision over, and no power to change any boundaries of municipal corporations fixed by a duly convened and elected legislative body, acting for the people in the State of Alabama.” 167 F.Supp. 405, 410. On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, affirmed the judgment, one judge dissenting. 270 F.2d 594. We brought the case here since serious questions were raised concerning the power of a State over its municipalities in relation to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. 362 U.S. 916.

At this stage of the litigation we are not concerned with the truth of the allegations, that is, the ability of petitioners to sustain their allegations by proof. The sole question is whether the allegations entitle them to make good on their claim that they are being denied rights under the United States Constitution. The complaint, charging that Act 140 is a device to disenfranchise Negro citizens, alleges the following facts: Prior to Act 140 the City of Tuskegee was square in shape; the Act transformed it into a strangely irregular twenty-eight-sided figure as indicated in the diagram appended to this opinion. The essential inevitable effect of this redefinition of Tuskegee’s boundaries is to remove from the city all save only four or five of its 400 Negro voters while not removing a single white voter or resident. The result of the Act is to deprive the Negro petitioners discriminatorily of the benefits of residence in Tuskegee, including, inter alia, the right to vote in municipal elections.

These allegations, if proven, would abundantly establish that Act 140 was not an ordinary geographic redistricting measure even within familiar abuses of gerrymandering. If these allegations upon a trial remained uncontradicted or unqualified, the conclusion would be irresistible, tantamount (be equivalent for) for all practical purposes to a mathematical demonstration, that the legislation is solely concerned with segregating white and colored voters by fencing Negro citizens out of town so as to deprive them of their pre-existing municipal vote.

It is difficult to appreciate what stands in the way of adjudging a statute having this inevitable effect invalid in light of the principles by which this Court must judge, and uniformly has judged, statutes that, howsoever speciously defined, obviously discriminate against colored citizens. “The [Fifteenth] Amendment nullifies sophisticated as well as simple-minded modes of discrimination.” Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 307 U. S. 275.

The complaint amply alleges a claim of racial discrimination. Against this claim the respondents have never suggested, either in their brief or in oral argument, any countervailing municipal function which Act 140 is designed to serve. The respondents invoke generalities expressing the State’s unrestricted power — unlimited, that is, by the United States Constitution — to establish, destroy, or reorganize by contraction or expansion its political subdivisions, to-wit, cities, counties, and other local units. We freely recognize the breadth (amplitud) and importance of this aspect of the State’s political power. To exalt this power into an absolute is to misconceive the reach and rule of this Court’s decisions in the leading case of Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 207 U. S. 161, and related cases relied upon by respondents.

The Hunter case involved a claim by citizens of Allegheny, Pennsylvania, that the General Assembly of that State could not direct a consolidation of their city and Pittsburgh over the objection of a majority of the Allegheny voters. It was alleged that, while Allegheny already had made numerous civic improvements, Pittsburgh was only then planning to undertake such improvements, and that the annexation would therefore greatly increase the tax burden on Allegheny residents. All that the case held was (1) that there is no implied contract between a city and its residents that their taxes will be spent solely for the benefit of that city, and (2) that a citizen of one municipality is not deprived of property without due process of law by being subjected to increased tax burdens as a result of the consolidation of his city with another. Related cases upon which the respondents also rely, such as Trenton v. New Jersey, 262 U. S. 182; Pawhuska v. Pawhuska Oil & Gas Co., 250 U. S. 394, and Laramie County v. Albany County, 92 U. S. 307, are far off the mark. They are authority only for the principle that no constitutionally protected contractual obligation arises between a State and its subordinate governmental entities solely as a result of their relationship.

In short, the cases that have come before this Court regarding legislation by States dealing with their political subdivisions fall into two classes:

(1) those in which it is claimed that the State, by virtue of the prohibition against impairment of the obligation of contract (Art. I, § 10) and of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, is without power to extinguish, or alter the boundaries of, an existing municipality; and

(2) in which it is claimed that the State has no power to change the identity of a municipality whereby citizens of a preexisting municipality suffer serious economic disadvantage.

Neither of these claims is supported by such a specific limitation upon State power as confines the States under the Fifteenth Amendment.

As to the first category, it is obvious that the creation of municipalities — clearly a political act — does not come within the conception of a contract under the Dartmouth College Case, 4 Wheat. 518.

As to the second, if one principle clearly emerges from the numerous decisions of this Court dealing with taxation, it is that the Due Process Clause affords no immunity against mere inequalities in tax burdens, nor does it afford protection against their increase as an indirect consequence of a State’s exercise of its political powers.

Particularly in dealing with claims under broad provisions of the Constitution, which derive content by an interpretive process of inclusion and exclusion, it is imperative that generalizations, based on and qualified by the concrete situations that gave rise to them, must not be applied out of context in disregard of variant controlling facts. Thus, a correct reading of the seemingly unconfined dicta of Hunter and kindred cases is not that the State has plenary power to manipulate in every conceivable way, for every conceivable purpose, the affairs of its municipal corporations, but rather that the State’s authority is unrestrained by the particular prohibitions of the Constitution considered in those cases.

The Hunter opinion itself intimates that a state legislature may not be omnipotent even as to the disposition of some types of property owned by municipal corporations, 207 U.S. at 207 U. S. 178-181. Further, other cases in this Court have refused to allow a State to abolish a municipality, or alter its boundaries, or merge it with another city, without preserving to the creditors of the old city some effective recourse for the collection of debts owed them. Shapleigh v. San Angelo, 167 U. S. 646; Mobile v. Watson, 116 U. S. 289; Mount Pleasant v. Beckwith, 100 U. S. 514; Broughton v. Pensacola, 93 U. S. 266. For example, in Mobile v. Watson, the Court said:

“Where the resource for the payment of the bonds of a municipal corporation is the power of taxation existing when the bonds were issued, any law which withdraws or limits the taxing power, and leaves no adequate means for the payment of the bonds, is forbidden by the constitution of the United States, and is null and void.” Mobile v. Watson, supra, at 116 U. S. 305.

This line of authority conclusively shows that the Court has never acknowledged that the States have power to do as they will with municipal corporations regardless of consequences. Legislative control of municipalities, no less than other state power, lies within the scope of relevant limitations imposed by the United States Constitution. The observation in Graham v. Folsom, 200 U. S. 248, 200 U. S. 253, becomes relevant: “The power of the state to alter or destroy its corporations is not greater than the power of the state to repeal its legislation.” In that case, which involved the attempt by state officials to evade the collection of taxes to discharge the obligations of an extinguished township, Mr. Justice McKenna, writing for the Court, went on to point out, with reference to the Mount Pleasant and Mobile cases:

“It was argued in those cases, as it is argued in this, that such alteration or destruction of the subordinate governmental divisions was a proper exercise of legislative power, to which creditors had to submit. The argument did not prevail. It was answered, as we now answer it, that such power, extensive though it is, is met and overcome by the provision of the Constitution of the United States which forbids a state from passing any law impairing the obligation of contracts. . . .” 200 U.S. at 200 U. S. 253-254.

If all this is so in regard to the constitutional protection of contracts, it should be equally true that, to paraphrase, such power, extensive though it is, is met and overcome by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which forbids a State from passing any law which deprives a citizen of his vote because of his race. The opposite conclusion, urged upon us by respondents, would sanction the achievement by a State of any impairment of voting rights whatever, so long as it was cloaked in the garb of the realignment of political subdivisions. “It is inconceivable that guaranties embedded in the Constitution of the United States may thus be manipulated out of existence.” Frost & Frost Trucking Co. v. Railroad Commission of California, 271 U. S. 583, 271 U. S. 594.

The respondents find another barrier to the trial of this case in Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549. In that case, the Court passed on an Illinois law governing the arrangement of congressional districts within that State. The complaint rested upon the disparity of population between the different districts which rendered the effectiveness of each individual’s vote in some districts far less than in others. This disparity came to pass solely through shifts in population between 1901, when Illinois organized its congressional districts, and 1946, when the complaint was lodged. During this entire period, elections were held under the districting scheme devised in 1901. The Court affirmed the dismissal of the complaint on the ground that it presented a subject not meet for adjudication. * The decisive facts in this case, which at this stage must be taken as proved, are wholly different from the considerations found controlling in Colegrove.

That case involved a complaint of discriminatory apportionment of congressional districts. The appellants in Colegrove complained only of a dilution of the strength of their votes as a result of legislative inaction over a course of many years. The petitioners here complain that affirmative legislative action deprives them of their votes and the consequent advantages that the ballot affords. When a legislature thus singles out a readily isolated segment of a racial minority for special discriminatory treatment, it violates the Fifteenth Amendment. In no case involving unequal weight in voting distribution that has come before the Court did the decision sanction a differentiation on racial lines whereby approval was given to unequivocal withdrawal of the vote solely from colored citizens. Apart from all else, these considerations lift this controversy out of the so-called “political” arena and into the conventional sphere of constitutional litigation.

In sum, as Mr. Justice Holmes remarked when dealing with a related situation in Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 273 U. S. 540, “Of course the petition concerns political action,” but “[t]he objection that the subject matter of the suit is political is little more than a play upon words.” A statute which is alleged to have worked unconstitutional deprivations of petitioners’ rights is not immune to attack simply because the mechanism employed by the legislature is a redefinition of municipal boundaries. According to the allegations here made, the Alabama Legislature has not merely redrawn the Tuskegee city limits with incidental inconvenience to the petitioners; it is more accurate to say that it has deprived the petitioners of the municipal franchise and consequent rights, and, to that end, it has incidentally changed the city’s boundaries. While in form this is merely an act redefining metes and bounds (land boundaries/limites), if the allegations are established, the inescapable human effect of this essay in geometry and geography is to despoil colored citizens, and only colored citizens, of their theretofore enjoyed voting rights. That was no Colegrove v. Green.

When a State exercises power wholly (completamente) within the domain of state interest, it is insulated from federal judicial review. But such insulation is not carried over when state power is used as an instrument for circumventing a federally protected right. This principle has had many applications. It has long been recognized in cases which have prohibited a State from exploiting a power acknowledged to be absolute in an isolated context to justify the imposition of an “unconstitutional condition.” What the Court has said in those cases is equally applicable here, viz. (namely; in other words), that “Acts generally lawful may become unlawful when done to accomplish an unlawful end, United States v. Reading Co., 226 U. S. 324, 226 U. S. 357, and a constitutional power cannot be used by way of condition to attain an unconstitutional result.” Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Foster, 247 U. S. 105, 247 U. S. 114. The petitioners are entitled to prove their allegations at trial.

For these reasons, the principal conclusions of the District Court and the Court of Appeals are clearly erroneous, and the decision below must be reversed.

Reversed.

MR. JUSTICE DOUGLAS, while joining the opinion of the Court, adheres to the dissents in Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549, and South v. Peters, 339 U. S. 276.

* Soon after the decision in the Colegrove case, Governor Dwight H. Green of Illinois, in his 1947 biennial message to the legislature, recommended a reapportionment. The legislature immediately responded, Ill.Sess.Laws 1947, p. 879, and, in 1951, redistricted again. Ill.Sess.Laws 1951, p. 1924.

APPENDIX TO OPINION OF THE COURT.

CHART SHOWING TUSKEGGEE, ALABAMA,

BEFORE AND AFTER ACT 140

The U.S. Supreme Court overturns a redistricting plan enacted by the Alabama legislature, which redrew the boundaries of the City of Tuskegee. The court found that the plan — which changed the city’s shape from a square to a 28-sided border (click on image to enlarge) — violated the 15th Amendment to the Constitution and was done expressly to exclude black voters from city elections. Image from: http://the60sat50.blogspot.com/2010/11/monday-november-14-1960-gomillion-v.html

(The entire area of the square comprised of the City prior to Act 140. The irregular black-bordered figure within the square represents the post-enactment city.)

MR. JUSTICE WHITTAKER, concurring.

I concur in the Court’s judgment, but not in the whole of its opinion. It seems to me that the decision should be rested not on the Fifteenth Amendment, but rather on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. I am doubtful that the averments of the complaint, taken for present purposes to be true, show a purpose by Act No. 140 to abridge petitioners’ “right . . . to vote” in the Fifteenth Amendment sense. It seems to me that the “right . . . to vote” that is guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment is but the same right to vote as is enjoyed by all others within the same election precinct, ward or other political division. And, inasmuch as no one has the right to vote in a political division, or in a local election concerning only an area in which he does not reside, it would seem to follow that one’s right to vote in Division A is not abridged by a redistricting that places his residence in Division B if he there enjoys the same voting privileges as all others in that Division, even though the redistricting was done by the State for the purpose of placing a racial group of citizens in Division B, rather than A.

But it does seem clear to me that accomplishment of a State’s purpose — to use the Court’s phrase — of “fencing Negro citizens out of” Division A and into Division B is an unlawful segregation of races of citizens, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, and, as stated, I would think the decision should be rested on that ground — which, incidentally, clearly would not involve, just as the cited cases did not involve, the Colegrove problem.

In: justia.com

* 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The 15th Amendment to the Constitution granted African American men the right to vote by declaring that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Although ratified on February 3, 1870, the promise of the 15th Amendment would not be fully realized for almost a century. Through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests and other means, Southern states were able to effectively disenfranchise African Americans. It would take the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 before the majority of African Americans in the South were registered to vote.

In: loc.gov

La obscena fortuna de los pastores evangélicos

Mientras mas educado seas difícilmente serás manipulado por estos líderes religiosos, gurus, pai, ni por nadie que piense que esta por encima de tu inteligencia o derechos. La educación es la verdadera llave hacia la libertad material y espiritual. La educación te da las herramientas para analizar, criticar y concluir sobre lo que otros te presenten como la verdad irrefutable.

En mi modesta opinión, los pastores evangélicos, las autoridades de la iglesia católica y cualquier otra autoridad religiosa debería vivir de acuerdo a como vivieron sus respectivos profetas y elegidos: En la pobreza material. Por ultimo, es muy interesante como este tipo de sectas y grupos religiosos son mas populares en distritos periféricos de Lima, pero difícilmente pueden instaurarse de la misma manera e intensidad en distritos de clase media-alta y alta (a pesar de que en estos, la fe es casi la misma aunque menos publica y descarada).

Video: Beto a Saber

Americanos por Accidente que Viven en el Extranjero y Luchan contra los Impuestos del Tio Sam

PARIS – Tom Wallis nació en los Estados Unidos pero pasó toda su vida en Francia,ahora resulta que el empresario de 40 años de edad que vive en Grenoble debe miles de dólares en impuestos a los Estados Unidos.

La madre de Wallis era francesa, pero tiene la ciudadanía estadounidense a través de su padre estadounidense. Anteriormente había visitado a la familia de su padre en los EE. UU., Pero aparte de ello, Wallis dice que no tiene una conexión real con el país.

A pesar de ello, hace tres años Wallis descubrió que todavía estaba sujeto a la ley de impuestos de los EE. UU.

El es uno de los potencialmente miles de “estadounidenses por accidente” en todo el mundo, ciudadanos estadounidenses que no viven en el país ni tienen vínculos reales con los Estados Unidos.

Bajo un sistema impositivo basado en la ciudadanía en los Estados Unidos, personas como Wallis están sujetas a los impuestos estadounidenses sobre sus ingresos globales, sin importar dónde vivan.

Wallis contrató consejo legal para completar la documentación necesaria para tratar de cumplir con la autoridad tributaria de los EE. UU., Pero cuando sus honorarios legales llegaron a más de $ 61,000 (50,000 euros), él dice que tuvo que detener el proceso. “Fue demasiado”, dijo.

Sus abogados le dijeron que él debería $ 115,000 en impuestos de EE.UU. después de la venta de su negocio en 2013, a pesar de que había pagado el impuesto a las ventas en Francia. Wallis dice que no pagará aunque los EE. UU. aún no le haya solicitado aun el pago del dinero formalmente.

“No hay forma”, dijo Wallis, y agregó que es dinero que podría invertir en Francia, donde vive su familia. “Estoy bien para pagar lo que debo en Francia, pero a los EE. UU. – No puedo aceptarlo … Creo que es un robo”.

Él dice que no sabe qué sucederá a continuación, pero que no se esconderá de las autoridades, porque siente que no ha hecho nada malo. “No pagaré. Incluso si tengo que ir a la cárcel, no lo pagaré con seguridad porque es demasiado injusto”.

Ha habido un movimiento creciente por parte de los “estadounidenses por accidente”, particularmente en Francia, para intentar que las autoridades estadounidenses se den cuenta de la carga que su ciudadanía estadounidense está agregando a sus vidas. Muchos esperan que el presidente francés, Emmanuel Macron, plantee el tema durante su visita de estado a los EE. UU. Esta semana.

Escrito por: by and

Traducido al español de: nbcnews

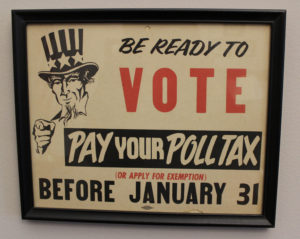

2014: Anti-poll tax amendment is 50 years old today

In 2016, Why Are Voters Still Paying Poll Taxes?. Image: http://images.huffingtonpost.com/2016-06-25-1466878976-2007786-PollTaxReceiptCropped.jpg

Fifty years ago today, the 24th Amendment, prohibiting the use of poll taxes as voting qualifications in federal elections, became part of the U.S. Constitution. Poll taxes were among the devices used by Southern states to restrict African Americans (as well as poor whites, Native Americans and other marginalized populations) from voting. The taxes had been ubiquitous across the old Confederacy earlier in the 20th century, but by 1964 only five states — Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas and Virginia — retained them.

The nominal amount of the taxes wasn’t very much, then or now. Alabama, Texas and Virginia set theirs at $1.50 per year, or $11.27 in today’s dollars; Arkansas had the lowest tax, $1 (or $7.51 today), while Mississippi’s was highest at $2 ($15.03 today). But the taxes were more onerous than they might appear. In Virginia, Alabama and Mississippi the taxes were cumulative, meaning a person seeking to vote had to pay the taxes for two or three years before they were eligible to register. Often only property owners were billed for the taxes, and the due dates were several months before the election. Virginia, Mississippi and Texas allowed cities and counties to impose local poll taxes on top of the state charge. And in some jurisdictions taxes had to be paid in person at the sheriff’s office, an intimidating prospect for many.

Also, as voting historian J. Morgan Kousser noted, the taxes had to be paid in cash, at a time when many black southerners had extremely low cash incomes: “[B]ecause sharecroppers, small farmers, factory workers, miners, and others bought most of their necessities on credit, they might not see more than a few dollars in cash during a year. To such men, who composed majorities or near-majorities of the adult male populations of every southern state at the turn of the century, a levy of a dollar or two might seem enormous and a cumulated poll tax, impossibly high.”

The 24th Amendment didn’t, however, mark the end of poll taxes in the United States. While it ended taxes as factors in federal elections, poll taxes remained in place for state and local elections. Arkansas effectively repealed its state poll tax in November 1964; it wasn’t till 1966 that the taxes in the four remaining states were struck down in a series of federal court decisions.

In: facttank

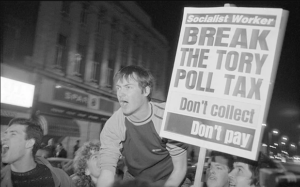

90’s: Las Protestas Anti Poll Taxes de Londres

Anti Poll Tax protest UK. Image: http://i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/02530/Anti-Poll_Tax_demo_2530713b.jpg

El Impuesto a la Comunidad o “Community Charge” (conocido también como “poll tax”) fue un sistema de impuestos introducido en reemplazo de los impuestos domésticos primero en Escocia en 1989 y luego en Inglaterra y Gales en 1990. El “Community Charge” estipulaba un impuesto individual de monto fijo per cápita para todo adulto en un porcentaje determinado por la autoridad local. Este impuesto fue establecido por la Primera Ministra Margareth Tatcher.

Debido a su impopularidad y constantes protestas de los ciudadanos, este impuesto tuvo que ser reemplazado por el “Council Tax” establecido por la Local Government Finance Act de 1992. Lo que llevó también a la caída política de Tatcher meses mas tarde.

Lectura recomendada: Las Protestas Anti Poll Tax – 20 años después de la violencia que sacudió Londres (2010)

Asterix y la Burocracia

China’s approach to eradicating poverty

Poverty is a global issue and poverty eradication must be a common task for those wishing to improve global governance. In Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the UN says: “We recognize that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for sustainable development.”

Guan Tzu, an ancient Chinese economist said: “When the granaries are full, they will know propriety and moderation; when their clothing and food are adequate, they will know the distinction between honour and shame.”

Poverty eradication will help reduce inequality and facilitate inclusive growth. If people living in poverty can shake off their plight, it can expand market capacity, enhance the specialized division of labour and facilitate a more efficient and unified large market. Moreover, the resulting strengthening of marginal propensity to consume (MPC) will inject new vigour and energy into economic growth.

As an ancient Chinese proverb goes: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” All sustainable and effective poverty alleviation measures ultimately rely on industrial development. Industrial development in poverty-stricken areas in China is hindered by many restrictions. We must raise the low level of industrial development in these regions and break away from the vicious circle of low-level industrial development, an unattractive investment environment and degrading industrial development.

To encourage self-driven growth and the development of a local market and businesses, it is imperative to introduce external market forces. Regional industrial funds can guide and integrate resources, such as funds, technologies and talent, for investment in market entities in specific regions. Industrial investment funds, which combine the industrial capital and resources of these areas, can improve employment opportunities for people in poverty and financial input in these areas, realizing poverty eradication in a fundamental way.

Efforts can be made to build capital strength for local enterprises and improve their corporate governance structures and management. For industrial development, steps can be taken to: advance the transformation and upgrading of traditional agriculture; cultivate new business sectors in rural areas; promote the integration of primary, secondary and tertiary industries; and bolster competition in rural industries. When it comes to society, endeavors can be made to optimize the investment environment and improve financing for small and medium businesses.

Newly-built residential buildings are seen next to the partially-frozen Songhua River and a bridge in Jilin, Jilin province February 3, 2015. Image: REUTERS/Stringer

To help remove the restrictions hindering the industrial development of poverty-stricken areas, the Chinese government has established two industrial poverty-alleviation funds. With the current total strength of 15 billion Renminbi yuan and the duration of 15 years, the two funds are expected to operate at a larger scale in the future. Both funds, operated and managed by State Development & Investment Corporation (SDIC), will follow market-oriented methods.

It is necessary to go off the beaten track and find innovative investment approaches for fund investment in impoverished areas. These might include integrating upper-stream industry chains with region-specific resources by cooperation with selected leading local enterprises, so that industries with local characteristics can move from disorderly competition towards benign development.

Investing in new business sectors, such as rural tourism, eco-agriculture and rural e-commerce, is also important. Furthermore, employing diverse investment methods, like sub-fund, debt investment and optimized direct investment, can attract more social investment for poverty alleviation and solve the problem of difficult and expensive financing for small and medium enterprises. If funds take advantage of their lengthy duration and low costs; work to support the talent, technological and managing advantages of leading enterprises; and invest in the resources and industries that demonstrate the local characteristics of the area, they can promote the ability of poverty-stricken areas to self-develop.

Poverty eradication is a common cause for all of society. China has developed a unique approach to this challenge by perpetually eliminating poverty through industrial development – a method of great significance for developing countries. Socially responsible enterprises must work together to declare a war on poverty and realize the great goal of “eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions” in the world.

Written by: Wang Huisheng, Chairman, State Development & Investment Corporation (SDIC)

In: webforum

Sacando tu IR de quinta

Para el caso de un trabajador dependiente que percibe S/. 4,000.00 nuevos soles mensuales:

1. REMUNERACIÓN BRUTA:

a. Para comenzar, el trabajador está obligado a pagar IR de quinta categoría si percibe ingresos anuales mayores a 7 UIT. La Unidad Impositiva Tributaria para el año 2013 asciende a S/. 3,700.00 nuevos soles (Decreto Supremo Nº 264-2012-EF)

Por lo tanto: S/. 3,700.00 nuevos soles x 7 = S/. 25,900.00 nuevos soles } monto referencial

b. Esos S/. 25,900.00 nuevos soles se dividen entre 14 sueldos que percibe el trabajador al año (remuneraciones y gratificaciones).

S/. 25,900.00 /14 = S/. 1,850.00 nuevos soles } quienes ganan hasta esta cantidad no están obligados a pagar IR de quinta categoría.

2. REMUNERACIÓN NETA:

Remuneración bruta anual – 7 UIT

S/. 4,000.00 nuevos soles x 14 sueldos – 7 x S/. 3,700.00 nuevos soles

S/. 56,000.00 nuevos soles – S/. 25,900.00 nuevos soles = S/. 30,100.00 nuevos soles } remuneración neta.

3. CÁLCULO DEL IMPUESTO:

a. Aplicación progresiva de tasas sobre la remuneración neta anual = S/. 30,100.00 nuevos soles.

Suma de la Renta Neta del Trabajo Tasa

y renta de fuente extranjera

1er tramo : Hasta 27 UIT 15%

2do tramo: Por el exceso de 27 UIT y hasta 54 UIT 21%

3er tramo: Por el exceso de 54 UIT 30%

27 UIT = S/. 99,900.00 nuevos soles.

54 UIT = S/. 199,800.00 nuevos soles.

b. Los S/. 30,100.00 nuevos soles se encuentran dentro del primer tramo, entonces se le aplica la tasa del 15%.

S/. 30,100.00 nuevos soles x 15% = S/. 4,515.00 nuevos soles } impuesto a la renta de quinta categoría a pagar en el año.

Actualización: Procedimiento IR con nuevos tramos