Beyond Trump’s Big, Beautiful Wall

Trump’s plan to wall off the entire U.S.-Mexico border is just one of a growing list of actions that extend U.S. border patrol efforts far past the international boundary itself.

By: Todd Miller & Joseph Nevins

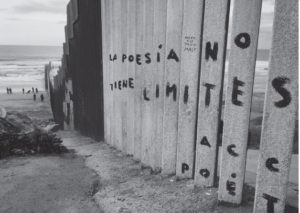

At the already existing border fence that divides Tijuana, Mexico, from Imperial Beach, California. KATIE SCHLECHTER. Image: http://tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10714839.2017.1331805

In the fall of 2016, Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful wall” along the U.S.-Mexico divide seemed like an unlikely presidential candidate’s campaign bluster. Since the New York real estate magnate’s swearing-in as Barack Obama’s White House successor on January 20, 2017, it is now a serious Executive Branch threat. Only five days after the inauguration, the Tweeter-in-Chief signed an executive order requiring “the immediate construction of a physical wall on the southern border.” It is to be one “monitored and supported by adequate personnel so as to prevent illegal immigration, drug and human trafficking, and acts of terrorism.” According to the administration’s official request for proposals, released on March 17, the wall should be “physically imposing in height”—about 30 feet high but certainly not less than 18 feet.

The new administration’s walled hopes and dreams face considerable obstacles. Among them are the fact that most people in the United States are opposed to building the new barrier, particularly one with a price tag of somewhere between $15 and $40 billion USD— or somewhere between 101 and 270 times the National Endowment for the Arts’ annual budget, estimates Carolina Miranda in the Los Angeles Times. According to an Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs poll in early April, only 28 percent of respondents support new spending for the border wall, with 58 percent against. The results are consistent with findings of a Quinnipiac survey from February. It found that 59 percent of voters opposed the construction of Trump’s wall, with 39 percent in favor; the gap only grew when voters were asked their opinions of the project if U.S. taxpayers had to finance it.

In addition, and perhaps most significant, is the matter of property. Most of the already-existing walls and fencing stand on federally-owned land. Much of the rest of the land where Trump’s Great Wall would be built is either privately-held or owned by Native tribes. Given this fact, the Trump administration will have a big legal battle on its hands that could involve years of litigation, predicts University of Pittsburgh law professor Gerald Dickinson in the Washington Post.

Regardless of the outcome of Trump’s plans for the wall along the actual international boundary line, it is but one part of a gigantic enforcement regime, one that already is comprised of approximately 18,000 Border Patrol agents in the Southwest borderlands alone (out of a total of roughly 22,000 agents nationally). The U.S.-Mexico borderlands is also already littered with several hundred miles of barricades—in the form of walls, fences, and low-lying vehicle barriers—almost all of which were constructed since the mid-1990s, across administrations, both Democratic and Republican. In some of the most urbanized stretches along the international divide, double-layered barriers exist. In and around San Diego, for example, a corrugated metal wall is paired with a steel mesh fence, portions of which are topped with concertina wire.

Moreover, the apparatus of exclusion goes far beyond the actual U.S.-Mexico divide. It includes a 100-mile-wide “border zone” inside the territorial perimeter of the United States, an area in which U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has certain extra-constitutional powers, such as the authority to set up immigration checkpoints. And there is also the interior policing apparatus run by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an agency with about 5,800 deportation officers, a force that Trump seeks to almost triple in size. Before even setting foot in the White House, Trump already had the largest border enforcement apparatus in U.S. history at his disposal. And with the definition of “operational control” for that apparatus altered in Trump’s January 2017 Border Security Executive Order—it now reads the “prevention of all unlawful entries” (emphasis added) into the United States—there is an anticipation of another massive border policing build-up.

This build-up will not only be at the Mexico-U.S. international boundary line, nor will it simply be within the United States’ own national territory. Rather, under Trump, we can expect an expansion of the apparatus of exclusion beyond the country’s official territorial boundaries. As then head of the U.S. Border Patrol Mike Fisher explained before the House Committee on Homeland Security in 2011, “The international boundary is no longer the first or last line of defense, but one of many.” This means there is not only an internal thickening of the border policing apparatus within the United States, but also a multilayered, extraterritorial extension of the border.

“The U.S. border starts at Guatemala now,” Daniel Ojalvo, a staff member at a migrant shelter in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, told a reporter from In These Times in 2015. In other words, greater efforts to stop migrants in southern Mexico and in Guatemala precede the Trump administration; in many ways, they are the product of Obama administration policies. With General John Kelly, the former head of U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), now at the helm of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), it is reasonable to expect such boundary “thickening” efforts—wall-building of a sort that rarely gets attention—to grow.

“South of the Border” and the New Boss

During his January confirmation hearing, General Kelly told senators that “a physical barrier will not do the job.” In an exchange with Senator John McCain (RAZ), he said that, as reported by the New York Times, “It has to be a layered defense. If you build a wall, you would still have to back that wall up with patrolling by human beings, by sensors, by observation devices.” In other words, border policing cannot be an “endless series of goal-line stands on the one-foot line,” to use Kelly’s words. Indeed, Trump’s handpicked Homeland Security chief stressed that he believed “the defense of the southwest border starts 1,500 miles south with great countries as far south as Peru.”

One of us saw this U.S. border extension up-close in Zacapa, Guatemala, in January 2017. At a Guatemalan military base, not far from Honduras, part of the 300-person-strong entity, called the Chorti border task force—named after the Indigenous people who live in the region—stood at attention. Established in 2014, the force demonstrated the construction of a roadside checkpoint during our visit. This included weaponizing six armored jeeps, which then tore through the roads of the military base at breakneck speeds, as if they were really in action.

When in 2008 the United States initiated the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI)—a military assistance cooperation with Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala—U.S. officials pointed to “border deficiencies” in the region as particularly problematic. Approximately $1.7 billion USD later, one of the solutions is the Chorti, which works hand-in-hand with a similar force on the Honduran side of the boundary as a binational border patrol. Guatemala also has a border force along its boundary with Mexico, known as the Tecun Uman. And in the works is a third Guatemalan border patrol, called the Xinca, which will patrol the Guatemala-El Salvador divide.

Before the border security demonstration on that sunny January day, the commanders of the Chorti force detailed, via slide show images, all the resources they obtained from the U.S. Embassy in 2016: assault rifles, night vision goggles, bullet-proof vests, a GPS digital map of Central America, 42 armored Jeeps, seven Ford F-450s, 25 Hilux pickups. Slides displayed pictures of U.S. military personnel training the new Guatemalan border patrol in both 2015 and 2016. Another slide detailed those trainings, which included the U.S. National Guard, BORTAC—the special forces unit of the U.S. Border Patrol—and a trip to Ft. Benning, Georgia, the location of the infamous the School of the Americas, which was rebranded as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC) in 2001.

Fernando Archila Gozalvo, an official from the Guatemalan Ministry of Interior, repeatedly stressed how the new security unit was part police force, part military force. For example, during the training operation that we witnessed, the military stood poised with assault rifles, carrying out perimeter surveillance, while the police set up a checkpoint, questioned the driver of a vehicle passing through that checkpoint, and then practiced pulling people from the car and handcuffing them. The Chorti border patrol had both a police commander and a military commander who wore a maroon beret, identifying himself as a Kaibil. Formed in 1975, Guatemala’s Kaibiles were a special counterinsurgency force modeled off, and initially trained by, the U.S. Green Berets. The 1999 report of the internationally supported Guatemalan Commission for Historical Clarification called the Kaibiles a “killing machine.”

Washington has long played a key role in the violence of everyday life in Central America and many Guatemalans see this type of border militarization as a continuation of that violent history. Serving the interests of the Boston-based United Fruit Company, the Eisenhower Administration played a key role in the overthrow of a democratically-elected government in Guatemala in 1954. In doing so, it laid the foundation for a series of military-dominated governments and the Guatemalan military’s reign of terror in the 1970s and 1980s. During that time, over 200,000 people—most of them Indigenous Mayans—lost their lives in the context of a brutal conflict between a U.S.- backed military oligarchy and guerrilla forces. The Commission for Historical Clarification concluded that the Guatemalan state was responsible for more than 90 percent of the deaths and had committed “acts of genocide.” The commission also found that U.S. training of members of Guatemala’s intelligence apparatus and officer corps in counterinsurgency “had significant bearing on human rights violations.” It additionally found that Washington, largely through its intelligence agencies, “lent direct and indirect support to some illegal state operations.”

The legacies of that conflict persist amidst the current wave of re-militarization in Guatemala. Even as the Trump administration threatens to cut different types of economic assistance, the bolstering of police and military to Central America is poised not only to continue, but to drastically increase under his regime, if the $54 billion USD proposed increase to the Pentagon’s already bloated 2018 budget is any indication. Under Trump, in Guatemala, it just might be that the past meets the present with even more force. And the Guatemalan past, as the presence of the Kaibil commander shows, still haunts everyday life. Indeed, the very military base in Zacapa where the Chorti border task force finished its trial operation was one of those places where many human rights violations committed by the U.S.-backed Guatemalan military happened. Former Guatemalan president Manuel Arana Osorio was even dubbed the “Butcher of Zacapa” for running brutal counterinsurgency operations in the region in the late 1960s, killing as many as 15,000 people.

So, it really shouldn’t have been a surprise that during the training that there was a U.S. military advisor—a major—on base, in a year-long detail to support the Chorti border patrol. Only now classic counterinsurgency has a new twenty-first century form: border militarization. As DHS Secretary John Kelly offered to the House of Representatives Homeland Security Committee in February 2017, the U.S. has a “great opportunity in Central America to capitalize on the region’s growing political will to combat criminal networks and control hemispheric migration.” Kelly contended that “leaders in many of our partner nations recognize the magnitude of the tasks ahead and are prepared to address them, but they need our support. As we learned in Colombia, sustained engagement by the United States can make a real and lasting difference.”

Back in Zacapa, after they finish up their checkpoint exercise, the soldiers and police of the Chorti task force talk about how they are separated from their families for weeks at a time to do the work of guarding Guatemala’s border from, according to their mission, the smuggling of narcotics and people heading north, most likely to the United States. Considering that more than 60 percent of the Guatemalan population live below the poverty line, there is no doubt that some of these agents have attempted to go north themselves. According to 2013 numbers, close to one million Guatemalans live in the United States.

In fact, the uniformed U.S. major, who made it quite clear right from the start that he wasn’t talking on behalf of the Embassy nor the military, indicated that he himself was from the U.S.-Mexico border region— more precisely, the city of Brownsville, Texas. On that military base, deep in Guatemala, he explained that his family had to make a choice in the late 1980s when the Reagan administration began to fortify the border: whether to stay in Mexico or move to the United States. He told of how the border had crossed his family: they moved to the United States from Mexico, and shortly thereafter, he joined the U.S. Army. Even as he did his job supporting the Chorti border force, with the blessing of DHS secretary John Kelly, he knew that every time his force drew a militarized boundary they were dividing families, friends, and entire communities.

As the major talked on that hot day at the Zacapa base, we could see the parched mountains surrounding where the Chorti force enacted their border exercise. Not only were we in the middle of the extending U.S. border regime, we were in the middle of the Central American dry corridor that extends through El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. According to climate scientist Chris Castro, the northern triangle of Central America is “ground zero” in Latin America for ecological upheavals in a changing and destabilizing climate. The thirsty mountains around us were one indication of a drought that was pushing parts of Guatemala into famine. In 2015, hundreds of thousands of people across Central America were pushed to the brink when the annual rains never arrived and harvests failed. Add to the mix the destructive superstorms and hurricanes that have battered the region and the northern triangle region represents a “catastrophic convergence,” to use the term of sociologist Christian Parenti, of political, economic, and ecological issues—all of which are compounding one another. At a global level, the United Nations predicts that by 2050, 250 million people will be displaced because of ecological disasters due to climate change.

The Trump administration will not only be deepening the violence and economic despair that propels people north from places like Guatemala through its border policies; through its embrace of climate change denialism and policies that will only increase U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, it will also be aiding a regional ecological crisis in Central America. And instead of stopping migration, such policies are likely to accelerate the forced displacement of possibly millions.

Where is the Wall?

As founder of the Global Detention Project Michael Flynn (not the Trump administration’s former national security advisor) described in a 2003 article published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and entitled “Donde está la frontera?” (Where is the Border?), the outward expansion of the U.S. border enforcement apparatus gives new meaning to the concept of a “wall.” According to Flynn, a wall is much more than a physical barrier. “U.S. border control efforts,” he argued, “have undergone a dramatic metamorphosis in recent years as the United States has attempted to implement practices aimed at stopping migrants long before they reach U.S. shores.”

These efforts manifest themselves not only in Guatemala, of course. They are present in many countries around the world. Agents from the special forces BORTAC unit have, according to CBP, “global response capability.” Agents from the unit have travelled to countries like Peru, Panama, Belize, Mexico, Honduras, and Ecuador to first provide a “diagnosis” of those countries’ respective borders, and then offer a “prescription” of training and resources to solve border “woes.” BORTAC has done this not only throughout Latin America, but also in other parts of the globe, including Iraq, where it trained border police and its tactical unit from 2006 to 2011.

As part of its own effort to spread “hard” borders across the globe, the U.S. State Department has also run training programs in countries that include Morocco, Algeria, Libya, and Turkey. These efforts are part of an initiative known as the Export Control & Related Border Security Program (EXBS). In addition to conducting trainings, EXBS has provided, as the State Department gushes, “state-of-the-art detection equipment and equipment training” to U.S. allies.

Since 2003, CBP has opened offices abroad, starting in Mexico City, Brussels, and Ottawa. Presently, there are 21 such CBP outposts in cities ranging from Panama City to Johannesburg to Cairo. Homeland Security has even set up “preclearance” sites in the airports of Shannon, Ireland and Vancouver, Canada. It was in this last city where, this past November, U.S. agents blocked Canadian journalist Ed Ou from boarding a flight headed to North Dakota. Ou was on his way to cover the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) stand-off at Standing Rock when CBP detained him for more than seven hours after he declined to give border agents the password to his phone. What Ou experienced in Canada was one small manifestation of an expensive and expansive regime of control and exclusion that will cost U.S. taxpayers approximately $20 billion USD in 2017, if you combine the budgets of both CBP and ICE. This constitutes a mammoth increase of approximately $1.5 billion USD over the annual budgets of the early 1990s.

It is on this already gargantuan budget that the Trump administration seeks to bestow even more largesse. According to the proposed budget for Fiscal Year 2018, Trump has a little over $2.5 billion USD designated for “tactical infrastructure” and other surveillance technology on the border, including money to “plan, design and begin building the wall.” This would amount to just a fraction of the total cost to construct what he promised during his campaign. Regardless, the physical wall that Trump envisions in the U.S.- Mexico borderlands is and should be a concern. As Verlon Jose, tribal chairman for the Tohono O’odham Nation, whose reservation in southern Arizona borders Mexico, declared in November 2016: “Over my dead body will a wall be built.” This sentiment resonates with many border residents along the 2,000-mile divide, who have voiced opposition.

While the U.S.-Mexico border wall may be the most xenophobic of symbols, it is just a small part of a policing apparatus that is spreading far beyond formal U.S. borders on waves of ever-increasing budgets for U.S. border and immigration control. As the pursuit of what is now called, in official parlance, “homeland security” has shown time and time again, such monies exact high human costs—from migrant deaths and divided families to myriad civil and human rights violations, and ecological degradation. It is this larger “prize” upon which we must focus, and that we must resist and ultimately eradicate.

Additional author information:

Todd Miller

Todd Miller is a journalist who lives in Tucson, Arizona. He is the author of Border Patrol Nation: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Homeland Security (City Lights Books, 2014) and the forthcoming Storming the Wall: Climate Change, Migration, and Homeland Security (City Lights, 2017).

Joseph Nevins

Joseph Nevins teaches geography at Vassar College. Among his books are Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid (City Lights Books, 2008), and Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War on “Illegals” and the Remaking of the U.S.-Mexico Boundary (Routledge, 2010).

In: tandfonline.com