Jennifer Aniston “no puede creer” la crítica de Vance a las mujeres sin hijos

Es realmente preocupante que un potencial Vicepresidente difunda estas ideas en sus votantes. Una pena.

Eclectic: Temas, eventos, cosas graciosas, recuerdos, suspicacias y otros mangos

Es realmente preocupante que un potencial Vicepresidente difunda estas ideas en sus votantes. Una pena.

Image: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/elections/win-democrats-n-c-supreme-court-strikes-down-redistricting-maps-n1288689

En una decision dividida, la Corte Suprema de Carolina del Norte anuló los nuevos mapas estatales que representan a los escaños del Congreso y de la Asamblea General del estado, asimismo, declaró que los tribunales estatales tenían autoridad para invalidar los límites diseñados por el partido republicano que tenían por finalidad asegurar una ventaja republicana de largo plazo en un estado que, al contrario, se encuentra altamente dividido.

A través de una decisión de 4-3, la Corte Suprema ordenó a la legislatura, controlada por el Partido Republicano, que rediseñe los planos antes del 18 de febrero y que explique cómo fue que calcularon la equidad partidista de estos nuevos límites. Cualquier mapa de reemplazo aún se puede utilizar para las elecciones primarias del 17 de mayo.

La decisión de la corte suprema revocó el fallo emitido en enero 2022 por un panel de tres jueces de primera instancia. La decision en mayoría declaró que la manipulación partidista en la redistribución de distritos aprobada por la legislatura en noviembre del año pasado violaba varias disposiciones de la Constitución de Carolina del Norte, entre ellos, el derecho a elecciones libres, libertad de expresión y protección igualitaria de los ciudadanos (protección igualitaria significa que una legislación que discrimina debe tener una base racional para hacerlo).

Los jueces de primera instancia habían encontrado amplia evidencia que demostraba que la legislatura había aprobado mapas que fueron “el resultado de una redistribución de distritos partidista pro-republicana realizada de manera intencional”. A pesar de ello, declararon que cuando se trataba de cuestionar la equidad partidista de estos planos y mapas, no le correspondía al poder judicial intervenir en su elaboración, ya que este deber le correspondía a la legislatura. Los jueces consideraron a este proceso de redistribución de distritos como algo inherentemente político y dijeron que muchas de estas demandas quedaban fuera del alcance de algún remedio legal.

Sin embargo, la mayoría en la Corte Suprema no estuvo de acuerdo con ellos, y dijo que es una obligación del poder judicial intervenir para bloquear los limites que sesgan el control de un partido en detrimento de aquellos con puntos de vista opuestos. Es posible que los candidatos anunciados para los puestos en los distritos tengan que reconsiderar su decision si se vuelven a trazar los límites de los distritos.

Esta decisión significa una gran victoria para los demócratas estatales, nacionales y también para sus aliados, quienes pusieron mucho esfuerzo y recursos en anular estos mapas y así bloquear los avances republicanos para la próxima década. Esto también podría dificultar que los republicanos retomen el control de la Cámara de Representantes este otoño. Un grupo asociado con el Comité Nacional Democrático de Redistribución de Distritos, encabezado por el ex-fiscal general de los Estados Unidos, Eric Holder, apoyó al bloque de votantes que presentó esta demanda.

Las demandas presentadas por los votantes y grupos de defensa fueron respaldadas por matemáticos e investigadores electorales quienes presentaron evidencia de su análisis sobre trillones de simulaciones de mapas. Estos especialistas testificaron que era muy probable que las nuevos limites le otorguen al Partido Republicano 10 de los 14 escaños de la Cámara de Representantes de EE.UU., así como mayorías en la Cámara y el Senado del estado en casi cualquier contexto político. Los republicanos actualmente tienen una ventaja de 8 frente a 5 escaños. Carolina del Norte esta en el puesto 14 en cuanto al crecimiento de la población según el censo.

Los demandantes argumentaron que los mapas aprobados por los legisladores republicanos habían frustrado la voluntad del pueblo de Carolina del Norte y que los límites deberían producir resultados políticos más acordes con los niveles de competitividad mostradas en elecciones estatales de la última década.

Los legisladores republicanos pretendían que se mantuviera el fallo de los jueces de primera instancia, cuando citaron que un fallo de la Corte Suprema de Carolina del Norte de principios de la década de 2000 decía que una ventaja partidista podia derivarse de la elaboración de mapas electorales. Ellos alegaron que el proceso de redistribución de distritos fue transparente y se prohibió el uso de datos raciales y políticos.

El presidente de la Corte Suprema, Paul Newby (de tendencia republicana), expresó en su voto singular que la mayoría de la corte pretendía “ocultar su sesgo partidista” a través de su decisión.

“Al optar por sostener que el gerrymandering partidista viola la Constitución de Carolina del Norte y al crear sus propios remedios, parece no haber límite para el poder de este tribunal”, escribió Newby.

Traducido de: NBC News: In a win for Democrats, N.C. Supreme Court strikes down redistricting maps

Video: Washington Post

Video: CrashCourse

Video: TED-Ed

Video: NPR

Video: PBS NewsHour

Nov 6, 2016 3:57 PM EDT

Cuando los redactores de la Constitución de los EE. UU. allá por el año 1787 consideraron si los Estados Unidos debería permitir que la gente eligiera a su presidente a través de una votación popular; uno de ellos, James Madison, dijo que los “negros” en el Sur representaban una “dificultad … de naturaleza seria”.

En ese mismo discurso fechado el jueves 19 de julio, Madison, en cambio, propuso el prototipo del sistema de Colegios Electorales que el país usa aun hoy. Bajo este sistema, cada estado tiene un número de votos electorales proporcionales a la población y el candidato que gana la mayoría de esos votos gana la elección.

Desde entonces, el sistema del Colegio Electoral le ha costado la carrera electoral a cuatro candidatos quienes perdieron la elección a pesar de haber ganado en el voto popular, uno de los casos más recientes es el del año 2000 en el cual Al Gore perdió la elección presidencial frente a George W. Bush. Tales anomalías y otras críticas han empujado a 10 estados demócratas a inscribirse en un sistema de votación popular. Y si bien hay muchas quejas sobre el Colegio Electoral, una de las que rara vez se aborda es la develada por un académico estudioso de la Constitución de los Estados Unidos: El Colegio Electoral fue creado para proteger la esclavitud, estableciendo las raíces de un sistema que es opresivo hasta el día de hoy.

“Es algo vergonzoso”, señaló Paul Finkelman, profesor visitante de derecho en la Universidad de Saskatchewan en Canadá. “Creo que si la mayoría de los estadounidenses supieran cuáles son los orígenes del Colegio Electoral, se sentirían disgustados”.

Madison, hoy conocido como el “Padre de la Constitución”, era dueño de esclavos en Virginia, que en ese entonces era el más poblado de los 13 estados si el cálculo de la población incluía a los esclavos negros que constituían alrededor del 40 por ciento de su población.

Durante ese discurso clave en la Convención Constitucional de Filadelfia, Madison dijo que con un voto popular, los estados del Sur “no podían influir en las elecciones al no contar a los negros”.

Madison era consciente de que el Norte superaría al Sur: A pesar de que más de medio millón de esclavos en el Sur eran parte de su poder económico, estos no podían votar. Su propuesta para el Colegio Electoral incluía el “compromiso de las tres quintas partes”, donde las personas negras podían contarse como las tres quintas partes de una persona, en lugar de una totalidad. Esta cláusula le otorgó al estado 12 de 91 votos electorales, más de una cuarta parte de lo que un presidente necesitaba para ganar.

“Nada de esto tenia que ver con esclavos que votan”, dijo Finkelman, quien escribió un artículo sobre los orígenes del Colegio Electoral para un simposio realizado luego de que Al Gore perdiera en las elecciones presidenciales. “Los debates son por una parte sobre el poder político pero también sobre la inmoralidad de contar esclavos con el propósito de dar poder político a la clase dominante”.

Finkelman indicó que la cláusula de tres quintos del Colegio Electoral permitió a Thomas Jefferson, quien era dueño de más de cien esclavos, vencer en 1800 a John Adams, quien se oponía a la esclavitud. Esto gracias a que el Sur contaba con ese gran bastión.

Mientras la esclavitud era abolida, y la Guerra Civil otorgaba la ciudadanía y el derecho al voto para los negros, el Colegio Electoral se mantuvo intacto. Otro profesor de derecho, que también ha sostenido que la Constitución tiene un cariz pro esclavitud, argumenta que aquella otorgó a los estados la autonomía para introducir leyes de voto discriminatorias, a pesar de la existencia de la Ley de Derecho al Voto de 1965 que fue desarrollada para justamente prevenirlas.

En el 2013, la Corte Suprema de los EE.UU. eximió a 9 estados, principalmente en el sur, de lo estipulado en la Ley de Derecho al Voto que disponía que los estados solo podían cambiar las leyes electorales con la aprobación del gobierno federal.

“Una Corte Suprema más conservadora ha estado desenredando lo que ha hecho la [otra] corte”, dijo Juan Perea, profesor de derecho de la Universidad Loyola de Chicago. “La falta de supervisión y uniformidad entre los estados funciona para preservar mucha desigualdad”.

En julio, un tribunal federal de apelaciones anuló una ley de identificación de votantes en Texas, dictaminando que discriminaba a los votantes negros y latinos al dificultarles el acceso a las cédulas de votación. Dos semanas después, otro tribunal federal de apelaciones dictaminó que Carolina del Norte, un estado oscilante clave, había aprobado disposiciones para el ejercicio del derecho al voto que “apuntaban a los afroamericanos con una precisión casi quirúrgica”.

Y para la ultima elección presidencial, 15 estados tuvieron nuevas restricciones de voto, como las que requieren una identificación con foto emitida por el gobierno en las urnas o reducir el número de horas que están abiertas.

“La capacidad de los estados para hacer más difícil el derecho al voto está directamente relacionada con el legado de la esclavitud”, dijo Perea. “Y esa capacidad para hacer que la votación sea más difícil generalmente se usa para privar de derechos a las personas de color”.

El Acuerdo Interestatal en Pro del Voto Popular Nacional (NPVIC) ha ganado fuerza, pero por motivos más relacionados con la anomalía de la contienda Gore-Bush. El asambleísta Jeffrey Dinowitz defendió una legislación en Nueva York que condujo al estado a apoyar el acuerdo. NewsHour Weekend le preguntó por qué el movimiento era importante.

“Somos la democracia más grande del planeta, y me parece que en la democracia más grande, la persona que obtenga la mayor cantidad de votos debería ganar las elecciones”, dijo Dinowitz. “Somos un país, Norte, Sur, Este y Oeste. Un país. Los votos de cada persona en el país deben ser iguales. Y en este momento, los votos no son iguales. En algunos estados tu voto es más importante que en otros estados “.

Nueva York aceptó abrumadoramente su proyecto de ley en 2014, uniéndose a otros nueve estados y Washington DC, que juntos, tienen 165 votos electorales. Si obtienen un total de 270 (la mayoría necesita elegir un presidente), la nación pasará a un voto popular.

No todos los académicos están de acuerdo en que la esclavitud fue la fuerza impulsora detrás del Colegio Electoral, aunque la mayoría está de acuerdo en que existe una conexión. Y tanto Perea como Finkelman saben que este no es el argumento más importante para el impulso hacia un voto popular.

“Pero es un vestigio que nunca se ha abordado”, dijo Perea.

Este artículo fue actualizado para reflejar el hecho de que Thomas Jefferson ganó la presidencia en 1800.

Por — Kamala Kelkar – @kkelkar

Kamala Kelkar works on investigative projects at PBS NewsHour Weekend. She has been a journalist for a decade, reporting from Oakland, India, Alaska and now New York.

Traducido al español de: PBS

Leer ademas:

The racial history of the Electoral College — and why efforts to change it have stalled

Así elige el “colegio electoral” al Presidente

Opinión: el Colegio Electoral, parte de un sistema deficiente

The Troubling Reason the Electoral College Exists

Es usted un peruano con residencia legal en el extranjero? Esta usted preocupado por no poder ir a votar en el referendum del 9 de diciembre de 2018? No se preocupe, de acuerdo al artículo 4 de la Ley N° 28859, a los peruanos en el exterior no se les sancionará con multa la omisión de sufragio.

LEY QUE SUPRIME LAS RESTRICCIONES CIVILES, COMERCIALES, ADMINISTRATIVAS

Y JUDICIALES; Y REDUCE LAS MULTAS EN FAVOR DE LOS CIUDADANOS OMISOS

AL SUFRAGIO

LEY N. 28859

(PUBLICADA EL 3 DE AGOSTO DE 2006)

“(…) Artículo 4.- Reduce la multa por omisión de sufragio, fija multa por no asistir o negarse a integrar o desempeñar el cargo de miembro de mesa de sufragio y elimina la multa para los peruanos en el exterior

Redúcese la multa por omisión de sufragio de cuatro por ciento (4%) de la Unidad Impositiva Tributaria; y confírmase la multa de cinco por ciento (5%) por no asistir o negarse a integrar la mesa de sufragio y por negarse a desempeñar el cargo de miembro de mesa, a las sanciones que se sujeta el Cuadro de Aplicación de Multas Diferenciadas según Niveles de Pobreza a que se contrae el artículo 5 de la presente Ley.

Para los peruanos en el exterior no se les sancionará con multa a la omisión de sufragio pero sí se aplicará la multa prevista para los peruanos residentes en el Perú, señalados en los literales a, b y c del artículo siguiente, solamente en los rubros, no asistencia o negarse a integrar mesa de sufragio; o, negarse al desempeño del cargo de miembro de mesa. (…)”

En: LEY N. 28859 (PUBLICADA EL 3 DE AGOSTO DE 2006)

Video: #WHYMAPS

La mayoria de los estados en USA tienen un método para que un votante elegible pueda emitir su voto antes del día de las elecciones. En 13 estados, el voto anticipado no esta disponible y una excusa o justificación es necesaria para solicitar una cédula para poder votar en ausencia.

Los estados pueden optar por proporcionar tres vías para que los votantes puedan votar antes del día de las elecciones:

Desplácese por el siguiente mapa para obtener detalles de estado por estado.

Mas informacion en: NCSL – ABSENTEE AND EARLY VOTING

By: Camila Domonoske

Image: This June, instructions wre posted at an early voting precinct in Bismarck, N.D. In that primary election, tribal IDs that did not show residential addresses were accepted as voter ID. But those same IDs will not be accepted in the general election.

James MacPherson/AP.

Native American groups in North Dakota are scrambling to help members acquire new addresses, and new IDs, in the few weeks remaining before Election Day — the only way that some residents will be able to vote.

This week, the Supreme Court declined to overturn North Dakota’s controversial voter ID law, which requires residents to show identification with a current street address. A P.O. box does not qualify.

Many Native American reservations, however, do not use physical street addresses. Native Americans are also overrepresented in the homeless population, according to the Urban Institute. As a result, Native residents often use P.O. boxes for their mailing addresses, and may rely on tribal identification that doesn’t list an address.

Those IDs used to be accepted at polling places — including in this year’s primary election — but will not be valid for the general election. And that decision became final less than a month before Election Day, after years of confusing court battles and alterations to the requirements.

Tens of thousands of North Dakotans, including Native and non-Native residents, do not have residential addresses on their IDs and will now find it harder to vote.

They will have the option of proving their residency with “supplemental documentation,” like utility bills, instead of their IDs, but according to court records, about 18,000 North Dakotans don’t have those documents, either.

And in North Dakota, unlike other states, every resident is eligible to vote without advance voter registration — so people might not discover the problem until they show up to cast their ballot.

North Dakota Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, a Democrat, is trailing her Republican opponent in her race for re-election. Native Americans tend to vote for Democrats.

The Republican-controlled state government says the voter ID requirement is necessary to connect voters with the correct ballot, and to prevent non-North Dakotans from signing up for North Dakota P.O. boxes and traveling to the state to vote fraudulently. In 2016, a judge overturning the law noted that voter fraud in North Dakota is “virtually non-existent.”

The state government says that residents without a street ID should contact their county’s 911 coordinator, to sign up for a free street address and request a letter confirming that address.

A group called Native Vote ND has been sharing those official instructions on Facebook.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is telling members to get in touch if they need help obtaining a residential address and updating their tribal ID. The tribe also says it will be sending drivers to take voters to the polls on Election Day.

“Native Americans can live on the reservations without an address. They’re living in accordance with the law and treaties, but now all of a sudden they can’t vote,” Standing Rock chairman Mike Faith said in a statement. “Our voices should be heard and they should be heard fairly at the polls just like all other Americans.”

Meanwhile, the Bismarck Tribune reports that a Native American organization is working to come up with a last-minute solution for voters who would otherwise be turned away:

“Bret Healy, a consultant for Four Directions, which is led by members of South Dakota’s Rosebud Sioux Tribe, said the organization believes it has a common-sense solution.

“The group is working with tribal leaders in North Dakota to have a tribal government official available at every polling place on reservations to issue a tribal voting letter that includes the eligible voter’s name, date of birth and residential address.”

A state official told tribal leaders that such letters will be accepted as proof of residency, the Tribune reports.

Heitkamp called the ID law “burdensome” and once again called for a law to protect the voting rights of Native Americans. She and other legislators have introduced such a bill year after year, unsuccessfully.

“Given the number of Native Americans who have served, fought, and died for this country, it is appalling that some people would still try and erect barriers to suppress their ability to vote,” Heitkamp said in a statement. “Native Americans served in the military before they were even allowed to vote, and they continue to serve at the highest rate of any population in this country.”

The ACLU said the Supreme Court’s decision “enables mass disenfranchisement.” “In an election that may wind up being decided by just a few thousand votes, the court’s decision could be deeply consequential for the country, not just those who live in North Dakota,” staff reporter Ashoka Mukpo wrote on Friday.

In 2016, the Harvard Law Review found that Native Americans “routinely face hurdles in exercising the right to vote and securing representation,” and that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was only a partial solution to the problem.

In: npr

Video: TV Perú Noticias

Video: La República

Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U.S. 339

Supreme Court of the United States

1960

MR. JUSTICE FRANKFURTER delivered the opinion of the Court.

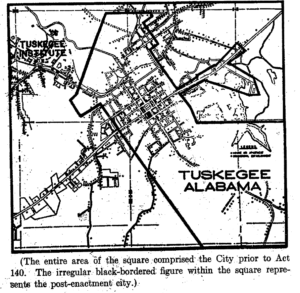

This litigation challenges the validity, under the United States Constitution, of Local Act No. 140, passed by the Legislature of Alabama in 1957, redefining the boundaries of the City of Tuskegee. Petitioners, Negro citizens of Alabama who were, at the time of this redistricting measure, residents of the City of Tuskegee, brought an action in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama for a declaratory judgment that Act 140 is unconstitutional, and for an injunction to restrain the Mayor and officers of Tuskegee and the officials of Macon County, Alabama, from enforcing the Act against them and other Negroes similarly situated. Petitioners’ claim is that enforcement of the statute, which alters the shape of Tuskegee from a square to an uncouth twenty-eight-sided figure, will constitute a discrimination against them in violation of the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and will deny them the right to vote in defiance of the Fifteenth Amendment.

The respondents moved for dismissal of the action for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted and for lack of jurisdiction of the District Court.

The court granted the motion, stating, “This Court has no control over, no supervision over, and no power to change any boundaries of municipal corporations fixed by a duly convened and elected legislative body, acting for the people in the State of Alabama.” 167 F.Supp. 405, 410. On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, affirmed the judgment, one judge dissenting. 270 F.2d 594. We brought the case here since serious questions were raised concerning the power of a State over its municipalities in relation to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. 362 U.S. 916.

At this stage of the litigation we are not concerned with the truth of the allegations, that is, the ability of petitioners to sustain their allegations by proof. The sole question is whether the allegations entitle them to make good on their claim that they are being denied rights under the United States Constitution. The complaint, charging that Act 140 is a device to disenfranchise Negro citizens, alleges the following facts: Prior to Act 140 the City of Tuskegee was square in shape; the Act transformed it into a strangely irregular twenty-eight-sided figure as indicated in the diagram appended to this opinion. The essential inevitable effect of this redefinition of Tuskegee’s boundaries is to remove from the city all save only four or five of its 400 Negro voters while not removing a single white voter or resident. The result of the Act is to deprive the Negro petitioners discriminatorily of the benefits of residence in Tuskegee, including, inter alia, the right to vote in municipal elections.

These allegations, if proven, would abundantly establish that Act 140 was not an ordinary geographic redistricting measure even within familiar abuses of gerrymandering. If these allegations upon a trial remained uncontradicted or unqualified, the conclusion would be irresistible, tantamount (be equivalent for) for all practical purposes to a mathematical demonstration, that the legislation is solely concerned with segregating white and colored voters by fencing Negro citizens out of town so as to deprive them of their pre-existing municipal vote.

It is difficult to appreciate what stands in the way of adjudging a statute having this inevitable effect invalid in light of the principles by which this Court must judge, and uniformly has judged, statutes that, howsoever speciously defined, obviously discriminate against colored citizens. “The [Fifteenth] Amendment nullifies sophisticated as well as simple-minded modes of discrimination.” Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 307 U. S. 275.

The complaint amply alleges a claim of racial discrimination. Against this claim the respondents have never suggested, either in their brief or in oral argument, any countervailing municipal function which Act 140 is designed to serve. The respondents invoke generalities expressing the State’s unrestricted power — unlimited, that is, by the United States Constitution — to establish, destroy, or reorganize by contraction or expansion its political subdivisions, to-wit, cities, counties, and other local units. We freely recognize the breadth (amplitud) and importance of this aspect of the State’s political power. To exalt this power into an absolute is to misconceive the reach and rule of this Court’s decisions in the leading case of Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 207 U. S. 161, and related cases relied upon by respondents.

The Hunter case involved a claim by citizens of Allegheny, Pennsylvania, that the General Assembly of that State could not direct a consolidation of their city and Pittsburgh over the objection of a majority of the Allegheny voters. It was alleged that, while Allegheny already had made numerous civic improvements, Pittsburgh was only then planning to undertake such improvements, and that the annexation would therefore greatly increase the tax burden on Allegheny residents. All that the case held was (1) that there is no implied contract between a city and its residents that their taxes will be spent solely for the benefit of that city, and (2) that a citizen of one municipality is not deprived of property without due process of law by being subjected to increased tax burdens as a result of the consolidation of his city with another. Related cases upon which the respondents also rely, such as Trenton v. New Jersey, 262 U. S. 182; Pawhuska v. Pawhuska Oil & Gas Co., 250 U. S. 394, and Laramie County v. Albany County, 92 U. S. 307, are far off the mark. They are authority only for the principle that no constitutionally protected contractual obligation arises between a State and its subordinate governmental entities solely as a result of their relationship.

In short, the cases that have come before this Court regarding legislation by States dealing with their political subdivisions fall into two classes:

(1) those in which it is claimed that the State, by virtue of the prohibition against impairment of the obligation of contract (Art. I, § 10) and of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, is without power to extinguish, or alter the boundaries of, an existing municipality; and

(2) in which it is claimed that the State has no power to change the identity of a municipality whereby citizens of a preexisting municipality suffer serious economic disadvantage.

Neither of these claims is supported by such a specific limitation upon State power as confines the States under the Fifteenth Amendment.

As to the first category, it is obvious that the creation of municipalities — clearly a political act — does not come within the conception of a contract under the Dartmouth College Case, 4 Wheat. 518.

As to the second, if one principle clearly emerges from the numerous decisions of this Court dealing with taxation, it is that the Due Process Clause affords no immunity against mere inequalities in tax burdens, nor does it afford protection against their increase as an indirect consequence of a State’s exercise of its political powers.

Particularly in dealing with claims under broad provisions of the Constitution, which derive content by an interpretive process of inclusion and exclusion, it is imperative that generalizations, based on and qualified by the concrete situations that gave rise to them, must not be applied out of context in disregard of variant controlling facts. Thus, a correct reading of the seemingly unconfined dicta of Hunter and kindred cases is not that the State has plenary power to manipulate in every conceivable way, for every conceivable purpose, the affairs of its municipal corporations, but rather that the State’s authority is unrestrained by the particular prohibitions of the Constitution considered in those cases.

The Hunter opinion itself intimates that a state legislature may not be omnipotent even as to the disposition of some types of property owned by municipal corporations, 207 U.S. at 207 U. S. 178-181. Further, other cases in this Court have refused to allow a State to abolish a municipality, or alter its boundaries, or merge it with another city, without preserving to the creditors of the old city some effective recourse for the collection of debts owed them. Shapleigh v. San Angelo, 167 U. S. 646; Mobile v. Watson, 116 U. S. 289; Mount Pleasant v. Beckwith, 100 U. S. 514; Broughton v. Pensacola, 93 U. S. 266. For example, in Mobile v. Watson, the Court said:

“Where the resource for the payment of the bonds of a municipal corporation is the power of taxation existing when the bonds were issued, any law which withdraws or limits the taxing power, and leaves no adequate means for the payment of the bonds, is forbidden by the constitution of the United States, and is null and void.” Mobile v. Watson, supra, at 116 U. S. 305.

This line of authority conclusively shows that the Court has never acknowledged that the States have power to do as they will with municipal corporations regardless of consequences. Legislative control of municipalities, no less than other state power, lies within the scope of relevant limitations imposed by the United States Constitution. The observation in Graham v. Folsom, 200 U. S. 248, 200 U. S. 253, becomes relevant: “The power of the state to alter or destroy its corporations is not greater than the power of the state to repeal its legislation.” In that case, which involved the attempt by state officials to evade the collection of taxes to discharge the obligations of an extinguished township, Mr. Justice McKenna, writing for the Court, went on to point out, with reference to the Mount Pleasant and Mobile cases:

“It was argued in those cases, as it is argued in this, that such alteration or destruction of the subordinate governmental divisions was a proper exercise of legislative power, to which creditors had to submit. The argument did not prevail. It was answered, as we now answer it, that such power, extensive though it is, is met and overcome by the provision of the Constitution of the United States which forbids a state from passing any law impairing the obligation of contracts. . . .” 200 U.S. at 200 U. S. 253-254.

If all this is so in regard to the constitutional protection of contracts, it should be equally true that, to paraphrase, such power, extensive though it is, is met and overcome by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which forbids a State from passing any law which deprives a citizen of his vote because of his race. The opposite conclusion, urged upon us by respondents, would sanction the achievement by a State of any impairment of voting rights whatever, so long as it was cloaked in the garb of the realignment of political subdivisions. “It is inconceivable that guaranties embedded in the Constitution of the United States may thus be manipulated out of existence.” Frost & Frost Trucking Co. v. Railroad Commission of California, 271 U. S. 583, 271 U. S. 594.

The respondents find another barrier to the trial of this case in Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549. In that case, the Court passed on an Illinois law governing the arrangement of congressional districts within that State. The complaint rested upon the disparity of population between the different districts which rendered the effectiveness of each individual’s vote in some districts far less than in others. This disparity came to pass solely through shifts in population between 1901, when Illinois organized its congressional districts, and 1946, when the complaint was lodged. During this entire period, elections were held under the districting scheme devised in 1901. The Court affirmed the dismissal of the complaint on the ground that it presented a subject not meet for adjudication. * The decisive facts in this case, which at this stage must be taken as proved, are wholly different from the considerations found controlling in Colegrove.

That case involved a complaint of discriminatory apportionment of congressional districts. The appellants in Colegrove complained only of a dilution of the strength of their votes as a result of legislative inaction over a course of many years. The petitioners here complain that affirmative legislative action deprives them of their votes and the consequent advantages that the ballot affords. When a legislature thus singles out a readily isolated segment of a racial minority for special discriminatory treatment, it violates the Fifteenth Amendment. In no case involving unequal weight in voting distribution that has come before the Court did the decision sanction a differentiation on racial lines whereby approval was given to unequivocal withdrawal of the vote solely from colored citizens. Apart from all else, these considerations lift this controversy out of the so-called “political” arena and into the conventional sphere of constitutional litigation.

In sum, as Mr. Justice Holmes remarked when dealing with a related situation in Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 273 U. S. 540, “Of course the petition concerns political action,” but “[t]he objection that the subject matter of the suit is political is little more than a play upon words.” A statute which is alleged to have worked unconstitutional deprivations of petitioners’ rights is not immune to attack simply because the mechanism employed by the legislature is a redefinition of municipal boundaries. According to the allegations here made, the Alabama Legislature has not merely redrawn the Tuskegee city limits with incidental inconvenience to the petitioners; it is more accurate to say that it has deprived the petitioners of the municipal franchise and consequent rights, and, to that end, it has incidentally changed the city’s boundaries. While in form this is merely an act redefining metes and bounds (land boundaries/limites), if the allegations are established, the inescapable human effect of this essay in geometry and geography is to despoil colored citizens, and only colored citizens, of their theretofore enjoyed voting rights. That was no Colegrove v. Green.

When a State exercises power wholly (completamente) within the domain of state interest, it is insulated from federal judicial review. But such insulation is not carried over when state power is used as an instrument for circumventing a federally protected right. This principle has had many applications. It has long been recognized in cases which have prohibited a State from exploiting a power acknowledged to be absolute in an isolated context to justify the imposition of an “unconstitutional condition.” What the Court has said in those cases is equally applicable here, viz. (namely; in other words), that “Acts generally lawful may become unlawful when done to accomplish an unlawful end, United States v. Reading Co., 226 U. S. 324, 226 U. S. 357, and a constitutional power cannot be used by way of condition to attain an unconstitutional result.” Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Foster, 247 U. S. 105, 247 U. S. 114. The petitioners are entitled to prove their allegations at trial.

For these reasons, the principal conclusions of the District Court and the Court of Appeals are clearly erroneous, and the decision below must be reversed.

Reversed.

MR. JUSTICE DOUGLAS, while joining the opinion of the Court, adheres to the dissents in Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549, and South v. Peters, 339 U. S. 276.

* Soon after the decision in the Colegrove case, Governor Dwight H. Green of Illinois, in his 1947 biennial message to the legislature, recommended a reapportionment. The legislature immediately responded, Ill.Sess.Laws 1947, p. 879, and, in 1951, redistricted again. Ill.Sess.Laws 1951, p. 1924.

APPENDIX TO OPINION OF THE COURT.

CHART SHOWING TUSKEGGEE, ALABAMA,

BEFORE AND AFTER ACT 140

The U.S. Supreme Court overturns a redistricting plan enacted by the Alabama legislature, which redrew the boundaries of the City of Tuskegee. The court found that the plan — which changed the city’s shape from a square to a 28-sided border (click on image to enlarge) — violated the 15th Amendment to the Constitution and was done expressly to exclude black voters from city elections. Image from: http://the60sat50.blogspot.com/2010/11/monday-november-14-1960-gomillion-v.html

(The entire area of the square comprised of the City prior to Act 140. The irregular black-bordered figure within the square represents the post-enactment city.)

MR. JUSTICE WHITTAKER, concurring.

I concur in the Court’s judgment, but not in the whole of its opinion. It seems to me that the decision should be rested not on the Fifteenth Amendment, but rather on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. I am doubtful that the averments of the complaint, taken for present purposes to be true, show a purpose by Act No. 140 to abridge petitioners’ “right . . . to vote” in the Fifteenth Amendment sense. It seems to me that the “right . . . to vote” that is guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment is but the same right to vote as is enjoyed by all others within the same election precinct, ward or other political division. And, inasmuch as no one has the right to vote in a political division, or in a local election concerning only an area in which he does not reside, it would seem to follow that one’s right to vote in Division A is not abridged by a redistricting that places his residence in Division B if he there enjoys the same voting privileges as all others in that Division, even though the redistricting was done by the State for the purpose of placing a racial group of citizens in Division B, rather than A.

But it does seem clear to me that accomplishment of a State’s purpose — to use the Court’s phrase — of “fencing Negro citizens out of” Division A and into Division B is an unlawful segregation of races of citizens, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, and, as stated, I would think the decision should be rested on that ground — which, incidentally, clearly would not involve, just as the cited cases did not involve, the Colegrove problem.

In: justia.com

* 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The 15th Amendment to the Constitution granted African American men the right to vote by declaring that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Although ratified on February 3, 1870, the promise of the 15th Amendment would not be fully realized for almost a century. Through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests and other means, Southern states were able to effectively disenfranchise African Americans. It would take the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 before the majority of African Americans in the South were registered to vote.

In: loc.gov