Categoría: medio ambiente

El fascinante mundo que se esconde bajo tus pies

Video: BBC News Mundo

Alemania con acento: Diego Castro, chef peruano

Video: DW Español

Tráfico ilegal de combustible convulsiona Madre de Dios

Imagen: http://img.uterodemarita.com.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/imagen-madre_de_dios6515663.jpg

Al grave problema social que significa la minería ilegal, se ha sumado el tráfico de combustible indiscriminado que han convertido nuevamente a Madre de Dios “en tierra de nadie, en donde la ley de la selva es la del más fuerte y la delincuencia campea poniendo en peligro la integridad de los habitantes de esa región”.

Así lo denunció el congresista Modesto Figueroa Minaya (FP) en el evento sobre “Lucha contra la Minería Ilegal y Tráfico Ilícito de Combustibles” en el cual participaron autoridades de Madre de Dios, del Ministerio de Energía y Minas y de la Marina de Guerra del Perú.

Señaló que los traficantes se transportan en canoas por el río Inambari llevando la carga ilegal en cilindros y llegan al lugar denominado La Pampa, en donde lo venden a los más de mil mineros ilegales que operan entre el kilómetro 100 y 140 de la Vía Interoceánica.

Informó que los traficantes proceden del Cusco y Puno y el combustible lo venden dos soles menos que la tarifa del mercado nacional, por lo cual se estima que la gasolina la obtienen de distribuidores informales de esas dos regiones o de Bolivia.

Se estima, de acuerdo al intenso trajín fluvial que realizan las canoas, los traficantes ganan entre dos y tres millones de soles diarios. Indicó que diariamente navegan entre 30 y 40 canoas y sus propietarios, resguardados por gente armada, se transportan libremente porque no hay control fluvial que impida el negocio ilegal.

Por tal motivo, dijo, pedirá a las autoridades de la Marina de Guerra, PNP, SUNAT y otras, a fin de que se ejecute un plan de control fluvial severo, para poner coto a este nuevo problema que ha surgido en Madre de Dios que tiene convulsionada a las comunidades ubicadas en las zonas de reserva natural y otras localidades del Tambopata.

El evento se realizó en el auditorio José Faustino Sánchez Carrión del Poder Legislativo.

En: peruinforma

Ver ademas: Oro ilegal ahoga la selva de Madre de Dios [FOTOS Y VIDEO]

¿Qué es el Codex Alimentarius?

Codex Alimentarius FAO. Imagen: http://www.nejvic-info.cz/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/codex-alimentarius.png

El Codex Alimentarius o “Código alimentario” fue establecido por la FAO y la Organización Mundial de la Salud en 1963 para elaborar normas alimentarias internacionales armonizadas, que protegen la salud de los consumidores y fomentan prácticas leales en el comercio de los alimentos. Más información…

¿Cuáles son las ventajas de las normas del Codex?

Las normas del Codex garantizan que los alimentos sean saludables y puedan comercializarse. Los 188 miembros del Codex han negociado recomendaciones con fundamento científico en todos los ámbitos relacionados con la inocuidad y calidad de los alimentos: higiene de los alimentos; límites máximos para aditivos alimentarios, residuos de plaguicidas y medicamentos veterinarios; y límites máximos y códigos para la prevención de la contaminación química y microbiológica. Los textos del Codex sobre inocuidad de los alimentos son una referencia en la solución de diferencias comerciales de la OMC. Más información…

Acerca del Codex

La finalidad del CODEX ALIMENTARIUS es garantizar alimentos inocuos y de calidad a todas las personas y en cualquier lugar.

El comercio internacional de alimentos existe desde hace miles de años pero, hasta no hace mucho, los alimentos se producían, vendían y consumían en el ámbito local. Durante el último siglo, la cantidad de alimentos comercializados a nivel internacional ha crecido exponencialmente y, hoy en día, una cantidad y variedad de alimentos antes nunca imaginada circula por todo el planeta.

El CODEX ALIMENTARIUS contribuye, a través de sus normas , directrices y códigos de prácticas alimentarias internacionales, a la inocuidad, la calidad y la equidad en el comercio internacional de alimentos. Los consumidores pueden confiar en que los productos alimentarios que compran son inocuos y de calidad y los importadores en que los alimentos que han encargado se ajustan a sus especificaciones.

Con frecuencia, las preocupaciones públicas relativas a las cuestiones de inocuidad de los alimentos sitúan al Codex en el centro de los debates mundiales. Entre los temas tratados en las reuniones del Codex se cuentan la biotecnología, los plaguicidas, los aditivos alimentarios y los contaminantes. Las normas del Codex se basan en la mejor información científica disponible, respaldada por órganos internacionales independientes de evaluación de riesgos o consultas especiales organizadas por la FAO y la OMS.

Aunque se trata de recomendaciones cuya aplicación por los miembros es facultativa, las normas del Codex sirven en muchas ocasiones de base para la legislación nacional.

El hecho de que existan referencias a las normas sobre inocuidad alimentaria del Codex en el Acuerdo sobre la Aplicación de Medidas Sanitarias y Fitosanitarias significa que el Codex tiene implicaciones de gran alcance para la resolución de diferencias comerciales. Se puede exigir a los miembros de la Organización Mundial del Comercio que justifiquen científicamente su intención de aplicar medidas más estrictas que las establecidas por el Codex en lo relativo a la inocuidad de los alimentos.

Los miembros del Codex abarcan el 99 % de la población mundial. Cada vez más países en desarrollo forman parte activa en el proceso del Codex, en muchos casos con el apoyo del Fondo fiduciario del Codex, que se esfuerza por proporcionar financiación y capacitación a los participantes de dichos países a fin de hacer posible una colaboración eficaz. El hecho de ser miembro activo del Codex ayuda a los países a competir en los complejos mercados mundiales y a mejorar la inocuidad alimentaria para su propia población. Paralelamente, los exportadores saben lo que demandan los importadores, los cuales, a su vez, están protegidos frente a las remesas que no cumplan las normas.

Las organizaciones gubernamentales y no gubernamentales internacionales pueden adquirir la condición de observadoras acreditadas del Codex para proporcionar información, asesoramiento y asistencia especializados a la Comisión.

Desde sus inicios en 1963, el sistema del Codex ha desarrollado una metodología abierta, transparente e inclusiva para hacer frente a los nuevos desafíos. El comercio internacional de alimentos es una industria que genera 200 000 millones de dólares al año y en la que se producen, comercializan y transportan miles de millones de toneladas de alimentos.

Es mucho lo que se ha puesto en juego para proteger la salud de los consumidores y asegurar la adopción de prácticas leales en el comercio alimentario.

Toda la información relativa al Codex es pública y gratuita. Para cualquier pregunta, sírvase contactar con la Secretaría del Codex.

Qué es el Codex

El Codex Alimentarius, o código alimentario, se ha convertido en un punto de referencia mundial para los consumidores, los productores y elaboradores de alimentos, los organismos nacionales de control de los alimentos y el comercio alimentario internacional. Su repercusión sobre el modo de pensar de quienes intervienen en la producción y elaboración de alimentos y quienes los consumen ha sido enorme. Su influencia se extiende a todos los continentes y su contribución a la protección de la salud de los consumidores y a la garantía de unas prácticas equitativas en el comercio alimentario es incalculable.

La importancia del Codex Alimentarius para la protección de la salud de los consumidores fue subrayada por la Resolución 39/248 de 1985 de las Naciones Unidas; en dicha Resolución se adoptaron directrices para elaborar y reforzar las políticas de protección del consumidor. En las directrices se recomienda que, al formular políticas y planes nacionales relativos a los alimentos, los gobiernos tengan en cuenta la necesidad de seguridad alimentaria de todos los consumidores y apoyen y, en la medida de lo posible, adopten las normas del Codex Alimentarius o, en su defecto, otras normas alimentarias internacionales de aceptación general.

El presente folleto se publicó por primera vez en 1999 con el objeto de promover una mayor comprensión de un código alimentario en evolución y de las actividades de la Comisión del Codex Alimentarius, el órgano competente para la compilación de normas, códigos de prácticas, directrices y recomendaciones que constituyen el Codex Alimentarius. Desde la primera publicación el modo de funcionamiento del Codex ha sufrido numerosas modificaciones. Por ello, la nueva edición de este folleto divulgativo es oportuna y necesaria para comprender el Codex Alimentarius en el siglo XXI.

La publicación “Que es el Codex” está disponible en inglés, francés, español, árabe,chino y ruso.

En: FAO

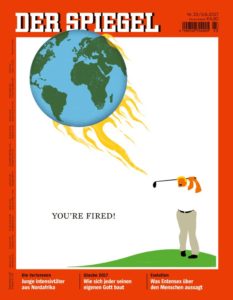

Der Spiegel: Paris Disagreement – Donald Trump’s Triumph of Stupidity

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other G-7 leaders did all they could to convince Trump to remain part of the Paris Agreement. But he didn’t listen. Instead, he evoked deep-seated nationalism and plunged the West into a conflict deeper than any since World War II. By SPIEGEL Staff

Until the very end, they tried behind closed doors to get him to change his mind. For the umpteenth time, they presented all the arguments — the humanitarian ones, the geopolitical ones and, of course, the economic ones. They listed the advantages for the economy and for American companies. They explained how limited the hardships would be.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel was the last one to speak, according to the secret minutes taken last Friday afternoon in the luxurious conference hotel in the Sicilian town of Taormina — meeting notes that DER SPIEGEL has been given access to. Leaders of the world’s seven most powerful economies were gathered around the table and the issues under discussion were the global economy and sustainable development.

The newly elected French president, Emmanuel Macron, went first. It makes sense that the Frenchman would defend the international treaty that bears the name of France’s capital: The Paris Agreement. “Climate change is real and it affects the poorest countries,” Macron said.

Then, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reminded the U.S. president how successful the fight against the ozone hole had been and how it had been possible to convince industry leaders to reduce emissions of the harmful gas.

Finally, it was Merkel’s turn. Renewable energies, said the chancellor, present significant economic opportunities. “If the world’s largest economic power were to pull out, the field would be left to the Chinese,” she warned. Xi Jinping is clever, she added, and would take advantage of the vacuum it created. Even the Saudis were preparing for the post-oil era, she continued, and saving energy is also a worthwhile goal for the economy for many other reasons, not just because of climate change.

But Donald Trump remained unconvinced. No matter how trenchant the argument presented by the increasingly frustrated group of world leaders, none of them had an effect. “For me,” the U.S. president said, “it’s easier to stay in than step out.” But environmental constraints were costing the American economy jobs, he said. And that was the only thing that mattered. Jobs, jobs, jobs.

At that point, it was clear to the rest of those seated around the table that they had lost him. Resigned, Macron admitted defeat. “Now China leads,” he said.

Still, it is likely that none of the G-7 heads of state and government expected the primitive brutality Trump would stoop to when announcing his withdrawal from the international community. Surrounded by sycophants in the Rose Garden at the White House, he didn’t just proclaim his withdrawal from the climate agreement, he sowed the seeds of international conflict. His speech was a break from centuries of Enlightenment and rationality. The president presented his political statement as a nationalist manifesto of the most imbecilic variety. It couldn’t have been any worse.

A Catastrophe for the Climate

His speech was packed with make-believe numbers from controversial or disproven studies. It was hypocritical and dishonest. In Trump’s mind, the climate agreement is an instrument allowing other countries to enrich themselves at the expense of the United States. “I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris,” he said. Trump left no doubt that the well-being of the American economy is the only value he understands. It’s no wonder that the other countries applauded when Washington signed the Paris Agreement, he said. “We don’t want other leaders and other countries laughing at us anymore. And they won’t be. They won’t be.”

Trump’s withdrawal is a catastrophe for the climate. The U.S. is the second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases — behind China — and is now no longer part of global efforts to put a stop to climate change. It’s America against the rest of the world, along with Syria and Nicaragua, the only other countries that haven’t signed the Paris deal.

But the effects on the geopolitical climate are likely to be just as catastrophic. Trump’s speech provided only the most recent proof that discord between the U.S. and Europe is deeper now than at any time since the end of World War II.

Now, the Western community of values is standing in opposition to Donald Trump. The G-7 has become the G-6. The West is divided.

For three-quarters of a century, the U.S. led and protected Europe. Despite all the mistakes and shortcomings exhibited by U.S. foreign policy, from Vietnam to Iraq, America’s claim to leadership of the free world was never seriously questioned.

That is now no longer the case. The U.S. is led by a president who feels more comfortable taking part in a Saudi Arabian sword dance than he does among his NATO allies. And the estrangement has accelerated in recent days. First came his blustering at the NATO summit in Brussels, then the disagreement over the climate deal in Sicily followed by Merkel’s speech in Bavaria, in which she called into question America’s reliability as a partner for Europe. A short time later, Trump took to Twitter to declare a trade war — and now, he has withdrawn the United States from international efforts to combat climate change.

A Downward Pointing Learning Curve

Many had thought that Trump could be controlled once he entered the White House, that the office of the presidency would bring him to reason. Berlin had placed its hopes in the moderating influence of his advisers and that there would be a sharp learning curve. Now that Trump has actually lived up to his threat to leave the climate deal, it is clear that if such a learning curve exists, it points downward.

The chancellor was long reluctant to make the rift visible. For Merkel, who grew up in communist East Germany, the alliance with the U.S. was always more than political calculation, it reflected her deepest political convictions. Now, she has — to a certain extent, at least — terminated the trans-Atlantic friendship with Trump’s America.

In doing so, the German chancellor has become Trump’s adversary on the international stage. And Merkel has accepted the challenge when it comes to trade policy and the quarrel over NATO finances. Now, she has done so as well on an issue that is near and dear to her heart: combating climate change.

Merkel’s aim is that of creating an alliance against Trump. If she can’t convince the U.S. president, her approach will be that of trying to isolate him. In Taormina, it was six countries against one. Should Trump not reverse course, she is hoping that the G-20 in Hamburg in July will end 19:1. Whether she will be successful is unclear.

Trump has identified Germany as his primary adversary. Since his inauguration in January, he has criticized no country — with the exception of North Korea and Iran — as vehemently as he has Germany. The country is “bad, very bad,” he said in Brussels last week. Behind closed doors at the NATO summit, Trump went after Germany, saying there were large and prosperous countries that were not living up to their alliance obligations.

And he wants to break Germany’s economic power. The trade deficit with Germany, he recently tweeted, is “very bad for U.S. This will change.”

An Extreme Test

Merkel’s verdict following Trump’s visit to Europe could hardly be worse. There has never been an open break with America since the end of World War II; the alienation between Germany and the U.S. has never been so large as it is today. When Merkel’s predecessor, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, refused to provide German backing for George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, his rebuff was limited to just one single issue. It was an extreme test of the trans-Atlantic relationship, to be sure, but in contrast to today, it was not a quarrel that called into question commonly held values like free trade, minority rights, press freedoms, the rule of law — and climate policies.

To truly understand the consequences of Trump’s decision, it is important to remember what climate change means for humanity — what is hidden behind the temperature curves and emission-reduction targets.

Climate change means that millions are threatened with starvation because rain has stopped falling in some regions of the planet. It means that sea levels are rising and islands and coastal zones are flooding. It means the melting of the ice caps, more powerful storms, heatwaves, water shortages and deadly epidemics. All of that leads to conflicts over increasingly limited resources, to flight and to migration.

In the U.S., too, there were plenty of voices warning the president of the consequences of his decision, Trump’s daughter Ivanka and her husband Jared Kushner among them. Others included cabinet members like Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Energy Rick Perry, along with pretty much the country’s entire business elite.

Companies from Exxon and Shell to Google, Apple and Amazon to Wal-Mart and PepsiCo all appealed to Trump to not isolate the U.S. on climate policy. They are worried about international competitive disadvantages in a world heading toward green energy, whether the U.S. is along for the ride or not. Google, Microsoft and Apple have long since begun drawing their energy from renewable sources, with the ultimate goal of complete freedom from fossil fuels. Wind and solar farms are booming in the U.S. — and hardly an investor can be found anymore for coal mining.

A long list of U.S. states, led by California, have charted courses that are in direct opposition to Trump’s climate policy. According to a survey conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, almost three-quarters of Americans are opposed to withdrawing from the Paris Agreement.

The Absurdity of Trump’s Histrionics

On the other side are right-wing nationalists such as Trump’s chief strategist Stephen Bannon, who deny climate change primarily because fighting it requires international cooperation. Powerful Republicans have criticized the climate deal with the most specious of all arguments. The U.S., they say, would be faced with legal consequences were it to miss or lower its climate targets.

Yet international agreement on the Paris accord was only possible because it contains no punitive tools at all. The only thing signatories must do is report every five years how much progress they have made toward achieving their self-identified climate protection measures.

Therein lies the absurdity of Trump’s histrionics. Nothing would have been easier for the U.S. than to take part pro forma in United Nations climate-related negotiations while completely ignoring climate protection measures at home — which Trump has been doing anyway since his election.

In late March, for example, he signed an executive order to unwind part of Barack Obama’s legacy, the Clean Power Plan. Among other measures, the plan called for the closure of aging coal-fired power plants, the reduction of methane emissions produced by oil and natural gas drilling, and stricter rules governing fuel efficiency in new vehicles. Without these measures, Obama’s goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by up to 28 percent by 2025, in comparison to 2005, will hardly be achievable. But Trump is also planning to head in the opposite direction. To make the U.S. less dependent on energy imports, he wants to return to coal, one of the dirtiest energy sources in existence — even though energy independence was largely achieved years ago thanks to cheap, less environmentally damaging natural gas.

German and European efforts will now focus on keeping the other agreement signatories on board, which Berlin has already been working on for several weeks now. Because of the now-visible effects of climate change and the falling prices for renewable energies, German officials believe that the path laid forward by Paris is irreversible.

Berlin officials say that EU member states are eager to move away from fossil fuels, as are China and India. Even emissaries from Russia and Saudi Arabia, countries whose governments aren’t generally considered to be enthusiastic promoters of renewable energy sources, have indicated to the Germans that “Paris will be complied with.” On Thursday in Berlin, Merkel and Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang demonstratively reaffirmed their support for the Paris Agreement. Keqiang even spoke of “green growth.”

China and India are likely to not just meet, but exceed their climate targets. China has been reducing its coal consumption for the last three years and plans for over 100 new coal-fired power plants have been scrapped. India, too, is abstaining from the construction of new coal-fired plants and will likely meet its goal of generating 40 percent of its electricity from non-fossil fuels by 2022, eight years earlier than planned. Both countries invest in solar and wind energy and in both, electricity from renewable sources is often cheaper than coal power.

Isolating the American President

The problem is that all of that still won’t be enough to limit global warming to significantly below 2 degrees Celsius, as called for in the Paris deal. Much more commitment, much more decisiveness is necessary, particularly in countries that can afford it. German, for example, is almost certain to fall short of its target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40 percent by 2020 relative to 1990.

In Taormina, Chancellor Merkel did all she could to isolate the American president. In the summit’s closing declaration, she wanted to specifically mention the conflict between the U.S. and its allies over the climate pact. Normally, such documents tend to remain silent on such differences.

At the G-20 meeting in Hamburg, Merkel plans to stay the course. She hopes that all other countries at the meeting will stand up to the United States. Even if Saudi Arabia ends up supporting its ally Trump, the end result would still be 18:2, which doesn’t look much better from the perspective of Washington.

Merkel, in any case, is doing all she can to ramp up the pressure on Trump. “The times in which we could completely rely on others are over to a certain extent,” she said in her beer tent speech last Sunday.

It shouldn’t be underestimated just how bitter it must have been for her to utter this sentence, and how deep her disappointment. Merkel, who grew up in the Soviet sphere of influence, never had much understanding for the anti-Americanism often found in western Germany. U.S. dependability is partly to thank for Eastern Europe’s post-1989 freedom.

Merkel has shown a surprising amount of passion for the trans-Atlantic relationship over the years. She came perilously close to openly supporting the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq and enjoyed a personal friendship with George W. Bush, despite the fact that most Germans had little sympathy for the U.S. president. Later, Merkel’s response to the NSA’s surveillance of her mobile phone was largely stoic and she also didn’t react when Trump called her refugee policies “insane.”

As such, Merkel’s comments last Sunday about her loss of trust in America were eye-opening. It was a completely new tone and Merkel knew that it would generate attention. Indeed, that’s what she wanted.

A Clear Message to the U.S.

Her sentence immediately circled the globe and was seen among Trump opponents as proof that the most powerful woman in Europe had lost hope that Trump could be brought to reason.

Prior to speeches to her party, such as the one held last Sunday, she always gets a manuscript from Christian Democratic Union (CDU) headquarters in Berlin, but she herself writes the most decisive passages. The comment about Europe’s allies was a clear message to the U.S., but it was also meant for a domestic audience. Her speech marked the launch of her re-election campaign.

Merkel knows that her campaign adversaries from the center-left Social Democrats (SPD) intend to make foreign policy an issue in the election. After all, it has a long history of doing so. Willy Brandt did so well in 1969 and 1972 in part because he called into question the Cold War course that had been charted to that point. Gerhard Schröder managed to win in 2002 in part because of his vociferous rejection of German involvement in the coming Iraq War.

Last Monday, German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel, a senior SPD member, took advantage of a roundtable discussion on migration in the Foreign Ministry to lay into Trump. The largest challenges we currently face, such as climate change, he said, have been made “even larger by the new U.S. isolationism.” Those who don’t resist such a political course, Gabriel continued, “make themselves complicit.” It was a clear shot at the chancellor.

But her speech last Sunday shielded Merkel from possible accusations of abetting Trump, though she nevertheless wants to keep the dialogue going with Washington. Speaking to conservative lawmakers in Berlin on Tuesday, she said that the trans-Atlantic relationship continues to be of “exceptional importance.” Nevertheless, she added, differences should not be swept under the rug.

Merkel realized early on just how difficult it would be to work with the new U.S. president, partly because she watched videos of some of his pre-inauguration appearances. Speaking to CDU leaders in December, she said that Trump was extremely serious about his slogan “America First.”

The chancellor’s image of Trump has shifted since then, but not for the better. The first contacts with the new government in Washington were sobering. When Christoph Heusgen, her foreign policy adviser, met for the first time with Michael Flynn, who was soon to become Trump’s short-lived national security adviser, he was shocked by his American counterpart’s lack of knowledge.

Shattered Hopes

But there were still grounds for optimism. Early on, Merkel thought that the new U.S. government’s naiveite might mean that Trump could be influenced. She was hoping to play the role of educator, an approach that initially looked like it might be successful. In a telephone conversation in January, Merkel explained to Trump the situation in Ukraine. She had the impression that he had never before seriously considered the issue and she was able to convince him not to lift the sanctions that had been placed on Russia.

The new president has likewise thus far refrained from moving the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. He has also left the Iran deal alone and revised initial statements in which he had said that NATO was “obsolete.” In the Chancellery, there was hope that Trump could in fact become something like a second-coming of Ronald Reagan.

Those hopes have now been shattered. Because Trump has had difficulty fulfilling many of his campaign promises, he has become even more intransigent. Merkel watched in annoyance as Trump did all he could in Saudi Arabia to avoid upsetting his hosts only to come to the NATO summit and cast public aspersions at his allies. The bad thing about Trump is not that he criticizes partners, says a confidante of Angela Merkel’s, but that in contrast to his predecessors, he calls the entire international order into question.

At one point, Merkel took Trump aside in Sicily to speak with him privately about climate protection and the president told her that he would prefer to delay his decision on the Paris Agreement until after the G-20 in July. You can postpone everything, Merkel replied, but it’s not helpful. She urged that he make a decision prior to the Hamburg summit.

He has now done so.

To the degree that one can make such a claim, Trump has a rather functional view of Merkel. He wants her to increase defense spending and to reduce Germany’s trade surplus with the U.S., even if it is a political impossibility. And he wants Merkel to force other European leaders to do the same, even though Merkel doesn’t possess the power to do so.

In Trump’s world, there are no allies and no mature relationships, just self-interested countries with short-term interests. History means nothing to Trump; as a hard-nosed real-estate magnate, he is only interested in immediate gains. He cares little for long-term relationships.

Two close advisers to the president contributed a piece to the Wall Street Journal this week that can be seen as something like a “Trump Doctrine.” “The world is not a ‘global community,'” wrote Gary Cohn and Herbert Raymond McMaster, Trump’s economic and security advisers. The subtext is clear: The global order, which the United States helped build, belongs to the past. There are no alliances anymore, just individual interests — no allies, just competitors. It was a clear signal to America’s erstwhile Western allies that they can no longer rely on the United States as a partner.

In: derspiegel

Disney CEO: I’m quitting advisory council over Paris deal

Bob Iger, the chairman and CEO of The Walt Disney Company, said Thursday that he is resigning from President Trump’s advisory council on policy over Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate deal.

Iger tweeted that he was resigning as “a matter of principle” in response to Trump’s formal announcement that he is pulling the U.S. from the Paris agreement.

As a matter of principle, I've resigned from the President's Council over the #ParisAgreement withdrawal.

— Robert Iger (@RobertIger) June 1, 2017

Iger joins Tesla CEO Elon Musk in resigning from the councils over Trump’s decision. Musk said Thursday that he would drop out of the two councils he was on, tweeting, “Climate change is real. Leaving Paris is not good for America or the world.”

Other CEOs said they would stay on the advisory councils, including Ginni Rometty of IBM, Brian Krzanich of Intel and Michael Dell of Dell.

In: thehill

Trump Paris fallout: Elon Musk steps down from WH councils

Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk is following through on his threat to step down from his positions on advisory councils in the White House after President Trump announced Thursday that the U.S. would withdraw from the Paris climate agreement.

Am departing presidential councils. Climate change is real. Leaving Paris is not good for America or the world.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) June 1, 2017

“Am departing presidential councils,” Musk tweeted on Thursday. “Climate change is real. Leaving Paris is not good for America or the world.”

On Wednesday afternoon, the tech billionaire tweeted that he made every effort to persuade Trump to not withdraw the U.S. from the Paris climate agreement and vowed to step down if the president did just that.

According to Musk’s tweets, he had lobbied Trump for months for the U.S. to not drop out of the agreement.

The Tesla CEO endured heavy criticism from some groups for accepting and then not stepping down from his role on Trump advisory councils. Musk argued that it was important to be a part of the conversations with the White House, regardless of who is president, to help shape discourse.

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick had previously stepped down from an advisory council in February, bowing to pressure from outside groups and vexed employees at Uber.

An IBM spokesperson said that CEO Ginni Rometty will not step down from her position on the White House’s strategic and policy advisory council. IBM has strongly supported the U.S. taking part in the agreement. Prior to Trump’s announcement to withdraw, the company reinforced its position with a blog post arguing the agreement’s importance on Thursday morning.

“As IBM has said before, there is value in engagement,” the spokesperson said. “We believe we can make a constructive contribution by having a direct dialogue with the Administration — as we do with governments around the world.”

Earlier Thursday, Intel CEO Brian Krzanich said on CNBC that even if Trump withdrew from the agreement — which Intel supports — he would remain on the council.

“Here’s my belief,” said Krzanich. “Just like exiting the Paris accord and walking away is not a good thing. Walking away from the administration — it is the administration of our country — we need to engage. And what I’ll do is I’ll spend time in there talking about ‘what are we going to do? How do we get back in.'”

Dell said that its CEO and founder Michael Dell would remain in his role on a Trump advisory board. A Dell spokesperson noted that they would continue to engage with “the Trump administration and governments around the globe to share our perspective on policy issues that affect our company, our customers and our employees.”

In: thehill

President Donald Trump announces U.S. will withdraw from Paris climate accord – Full speech

¿Qué significa que Trump saque a EEUU del Acuerdo de París contra el cambio climático?

Solo había dos países pertenecientes a Naciones Unidas que no apoyasen el pacto contra el calentamiento del planeta: Siria y Nicaragua. Ahora ya son tres.

Corporates eating the world. Imagen: http://socialistnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/corporates-eating-the-world.jpg

Las consecuencias de que el presidente Donald Trump retire a Estados Unidos del Acuerdo de París contra el cambio climático son muchas y complejas, la mayoría negativas. No obstante, al margen de especulaciones, hay algunas cuestiones claras:

1. EEUU se retira de un pacto mundial que apoya hasta Corea del Norte

Lo primero es que EEUU deja un pacto que es apoyado por otras 193 naciones del planeta ( aquí está la lista), prácticamente todos los países de la Tierra. Solo hay dos pertenecientes a Naciones Unidas que no están: Siria y Nicaragua. Pero todos los demás lo firmaron, incluso la Corea del Norte de Kim Jong Un.

Tras aprobarse un acuerdo internacional de este tipo, luego hay que esperar un tiempo hasta que se suman las ratificaciones de países suficientes para que entre en vigor. El pacto de París es el acuerdo internacional que más rápido ha conseguido su ratificación en la historia de Naciones Unidas.

La salida de EEUU no va a gustar al resto del planeta y va a provocar reacciones. La expresidenta irlandesa Mary Robinson ya había adelantado que, si Estados Unidos decidía retirarse de los compromisos asumidos en el Acuerdo de París contra el cambio climático, se convertiría en “un estado paria”.

2. El segundo emisor de CO2 deja a los otros el problema de cambio climático

El Acuerdo de París supuso un hito justamente por unir a tantos países de la Tierra contra el cambio climático, aunque no todos tienen la misma responsabilidad en este problema. Dentro del pacto están los países más industrializados que históricamente son los más culpables de que el planeta se esté calentando a causa de los gases de efecto invernadero lanzados a la atmósfera desde la Revolución Industrial por la quema de carbón o petróleo(como la UE, EEUU, Japón, Canadá, Rusia…). También incluye a las naciones emergentes que sin haberlo causado sí que resultan ahora decisivas para resolver el problema (como China, India, Brasil…). Y cuenta además con el apoyo de las naciones petroleras (Arabia Saudita, Qatar…) o el conjunto de los países en desarrollo.

La salida de EEUU supone que el que es hoy el segundo mayor emisor de gases de CO2 en el mundo (el primero es China) y el mayor emisor histórico desde la Revolución Industrial deja a todos los demás que resuelvan el problema. Por un lado, esto hace mucho más difícil el esfuerzo colectivo para que el aumento de la temperatura media del planeta no suba más de 2 °C (3.7°F).

Pero además provoca una muy injusta paradoja: que otros países mucho más pobres y sin ninguna culpa (incluso naciones africanas como República Democrática del Congo, Burundi, Liberia…) contribuyan al esfuerzo internacional contra el cambio climático, mientras el principal responsable mira hacia otro lado.

3. Pone en peligro la mayor oportunidad para luchar contra el cambio climático

Antes del Acuerdo de París, Naciones Unidas ya consiguió que se aprobase un tratado contra el cambio climático: el llamado Protocolo de Kioto (que obligaba a reducir emisiones solo a los países más ricos). Sin embargo, se quedó prácticamente en nada. En aquella ocasión el motivo fue… EEUU. Después de años de negociaciones, en 2001 el presidente George W. Bush decidió no ratificar el tratado.

Tras este revés, tuvieron que pasar 14 años hasta que se consiguió cerrar de nuevo un acuerdo, el de París, que por primera vez involucraba a todos los países en la lucha contra el cambio climático.

No cabe duda que la retirada de EEUU pone en peligro la mejor oportunidad que se tiene ahora mismo para luchar de forma colectiva contra el cambio climático antes de que sea ya demasiado tarde. Algunos países que se sumaron al pacto en 2015 por la presión de quedarse aislados podrían aprovechar ahora para seguir la senda de EEUU, lo que haría saltar por los aires el acuerdo. Aunque también puede pasar todo lo contrario: que todas las naciones consoliden más su unión como respuesta a EEUU. Ninguno de los dos escenarios parecen positivos para el país que preside Trump.

De momento, China y la UE ya han asegurado que continuarán con el Acuerdo de París aunque no esté EEUU.

4. Para EEUU no cambia tanto el dejarlo o no

Paradójicamente, no cambia tanto para EEUU abandonar o no el Acuerdo de París desde el punto de vista de sus acciones internas. Es de suponer que alguien se lo habrá explicado al presidente Trump, pero este pacto climático no fija obligaciones de reducción de gases para los países, sino que solo les compromete a cumplir sus propios planes nacionales ( aquí el texto del acuerdo). Se diseñó así para conseguir el apoyo de todos y para evitar el rechazo específico de EEUU.

Esto quiere decir que la política climática de EEUU no viene marcada por Naciones Unidas, sino por las normas que se pongan en marcha en el país. Hasta la llegada de Trump, estas políticas se basaban principalmente en el Plan de Energía Limpia de Obama. Pero este programa quedó bloqueado en la Corte Suprema y el nuevo presidente ya ha dado los primeros pasos para desmantelarlo.

Si el objetivo de EEUU con Obama era que EEUU redujera sus emisiones entre un 26% y un 28% para 2025 con respecto a los niveles de 2005, la consultora Rhodium Group estimó que si se cancelan las políticas energéticas del gobierno anterior entonces no se llegará a una disminución del 14%, aunque se hubiera seguido en el Acuerdo de París.

El pacto de Naciones Unidas tampoco incluye sanciones si no se cumplen los objetivos nacionales. Solo compromete a los países a presentar información transparente sobre sus emisiones para poder seguir sus progresos y, en caso de no alcanzar sus objetivos nacionales, prevé simplemente que entre en acción un comité de carácter facilitador.

Quizá Trump se planteó dejar el pacto de París para no tener que dar explicaciones sobre lo que emita o no EEUU. Pero es probable que su salida aumente todavía más la presión sobre lo que haga en materia climática. Si los otros países del mundo realizan esfuerzos para reducir sus emisiones, seguro que reclaman lo mismo a Trump, esté o no en el pacto.

5. Más tensiones entre los países y retrasos

¿La decisión de Trump hará que se dejen de realizar esfuerzos para reducir las emisiones o que salte por los aires el gran pacto internacional contra el cambio climático? Es muy difícil saber hasta qué punto puede perjudicar una decisión así la lucha contra el cambio climático. En gran medida dependerá de cómo reaccione el resto del mundo. Como hemos visto en el punto anterior, Trump puede desmantelar toda la política climática de EEUU esté dentro o no de París. Ahora bien, hay muchas empresas y estados en el país que van hace tiempo en una dirección muy distinta a la del presidente. Este miércoles, la ciudad de Nueva York mostró su compromiso con el pacto de París esté EEUU dentro o no.

No es muy creíble que Trump pueda acabar con la transformación del mundo hacia unas energías más limpias. Ahora bien, seguro que todo esto puede retrasarlo y también generar muchas tensiones entre los países.

En: univision