Breaking Up to Stay Together: Iraq in Pieces

By Ali Khedery

American leaders contemplating Iraq have made a habit of substituting unpleasant realities with rosy assessments based on questionable assumptions. In 1991, after the Gulf War, the George H. W. Bush administration hoped that Iraqis would rise up against Saddam Hussein and encouraged them to do so, only to abandon them to the Republican Guard. In 1998, President Bill Clinton signed the Iraq Liberation Act, officially embracing regime change and transferring millions of dollars to an Iranian-backed convicted embezzler, Ahmed Chalabi. In 2003, the George W. Bush administration assumed that toppling Saddam would lead to stability rather than chaos when the U.S. military “shocked and awed” its way to Baghdad. In 2005, as the country descended into violence, Vice President Dick Cheney insisted that the insurgency was in its “last throes.”

In 2010, still flushed with the success of Bush’s “surge,” Vice President Joe Biden forecast that President Barack Obama’s Iraq policy was “going to be one of the great achievements of this administration,” lauding Iraqis for using “the political process, rather than guns, to settle their differences.” And in 2012, even as Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was running an increasingly authoritarian and dysfunctional regime, the administration continued its happy talk. “Many predicted that the violence would return and Iraq would slide back toward sectarian war,” said Antony Blinken, then Biden’s national security adviser. “Those predictions proved wrong.”

Today, of course, the Iraqi army has all but collapsed, despite some $25 billion in U.S. assistance. Shiite militants who have sworn allegiance to Iran’s supreme leader operate with impunity. And the Islamic State (or ISIS) dominates more than a third of Iraq and half of Syria. Obama’s successor will thus certainly earn the distinction of becoming the fifth consecutive president to bomb Iraq.

Still, the next resident of the White House can choose to avoid the mistakes of his or her predecessors by refusing to unconditionally empower corrupt and divisive Iraqi leaders in the hope that they will somehow create a stable, prosperous country. If Iraq continues on its current downward spiral, as is virtually certain, Washington should accept the fractious reality on the ground, abandon its fixation with artificial borders, and start allowing the various parts of Iraq and Syria to embark on the journey to self-determination. That process would no doubt be rocky and even bloody, but at this point, it represents the best chance of containing the sectarian violence and protecting the remainder of the Middle East from still further chaos.

DECLINE AND FALL

Since the founding of modern Iraq in 1920, the country has rarely witnessed extended peace and stability. Under the Ottoman Empire, the sultans ruled the territory as three separate vilayat, or provinces, with governors independently administering Mosul in the north, Baghdad in the center, and Basra in the south. After the Allied victory in World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, however, the Treaty of Sèvres created new and artificial borders to divide the spoils. France assumed a mandate over the Levant, and the British were determined to carve out a sphere of influence in oil-rich Mesopotamia, installing a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, Faisal bin al-Hussein, as Iraq’s first monarch in 1921.

By 1932, however, King Faisal I had already concluded that Iraq made little sense as a nation:

With my heart filled with sadness, I have to say that it is my belief that there is no Iraqi people inside Iraq. There are only diverse groups with no national sentiments. They are filled with superstitious and false religious traditions with no common grounds between them. They easily accept rumors and are prone to chaos, prepared always to revolt against any government.

Those words would prove prophetic, and in 1958, his grandson, Faisal II, was murdered in a coup d’état along with the royal family. Three revolutions and counterrevolutions followed before the Arab Socialist Baath Party took power in 1968, with Saddam seizing total control in 1979.

Once the center of regional politics, science, culture, and commerce, Iraq regressed on every front under Saddam. In the 1980s, his Anfal campaign exterminated tens of thousands of Kurds, and his disastrous war with Iran left hundreds of thousands dead and millions displaced. His equally catastrophic incursion into Kuwait in 1990 led to a lost war, the ruthless suppression of Kurdish and Shiite rebellions, a dozen years of devastating sanctions, and some $130 billion in debt. Not even Saddam’s core constituency of Sunnis was immune from frequent pogroms; countless relatives of Saddam, party officials, generals, and tribal chieftains were liquidated over the years. These decades of misrule caused a majority of Iraqis—not just Kurds and Shiites but also exiled Islamists and secular Sunnis—to reject Baghdad’s rule.

The post-Saddam Iraq that emerged after the 2003 U.S. invasion was supposed to be different. Having failed to unearth weapons of mass destruction, the United States expended an extraordinary amount of resources to compensate for the error and pursue pluralism, stability, prosperity, democracy, and good governance. Some 4,500 U.S. soldiers were killed and 32,000 wounded, not to mention the trillions of dollars in direct and indirect costs and the millions of dead or displaced Iraqis. Yet the intervention ultimately failed, because it empowered a new set of elites who drew their legitimacy almost purely from divisive ethno-sectarian agendas rather than from visions of truth, reconciliation, the rule of law, and national unity.

Shortly after the invasion, Machiavellian politicians pressed U.S. officials to disband the Iraqi army as they hijacked the U.S.-instituted De-Baathification Commission and used it to extort or purge their secular political opponents, Sunni and Shiite alike. Hundreds of thousands were left permanently unemployed, embittered, and primed to seek violent retribution against the new order.

In the mountainous north, Kurdish leaders sought to consolidate the considerable gains they had achieved through self-governance following the introduction of a no-fly zone in 1991. After a vicious civil war in the mid-1990s, they established the semiautonomous Kurdistan Region, securing peace and attracting foreign investment. Once Saddam was gone, they maintained control of key positions in Baghdad under a new ethno-sectarian quota system as a hedge against further repression.

In the south, the Shiite Islamist parties that had battled Saddam’s secular Baath Party for decades, often with Iran’s covert support, emerged victorious and sought to compensate for past repression. They asserted their will as the majority by defying the Baath’s taboos and establishing numerous official religious holidays, cementing their brand of religious values in the national school curriculum, and placing members of the armed wings of their religious political parties on government payrolls. In the halls of power in Baghdad, the word of Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the highest authority in Shiite Islam, reigned supreme.

Iraq’s minority Sunnis, the nation’s ruling elite for centuries, found themselves in disarray. To correct perceived injustices, they eventually settled on a strategy of boycotting democracy in favor of insurgency and terrorism. Hopelessly divided and lacking leadership and vision, Sunni Arabs often fell into the trap of battling the U.S. military occupation and the surging influence of their historical arch-nemesis, Shiite Persian Iran, by striking a deal with the devil: al Qaeda.

So began an endless cycle of killing among militant radicals of all stripes, from remnants of the Baath Party to al Qaeda in Iraq to the Iranian-backed Shiite militias. With each religiously charged atrocity, the Iraqi national identity grew weaker, and the millennia-old senses of self—tribal, ethnic, and religious—grew stronger.

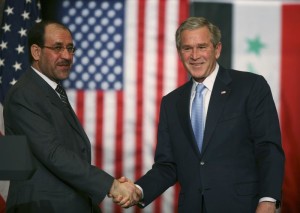

Iraq’s Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki (L) shakes hands with U.S. President George W. Bush in Amman, November, 2006. ALI JAREKJI / REUTERS

Of all the main forces, perhaps the single most corrosive was Maliki, a duplicitous and divisive politician who served as prime minister beginning in 2006. After he lost the 2010 elections, he managed to stay in office through a power-sharing deal backed by Washington and Tehran, only to consolidate his authority further by retaining personal control of the interior, defense, and intelligence ministries, among other important bodies. With Obama distracted by the global economic meltdown and advised by top aides that Maliki was a nationalist rather than a sectarian, the prime minister secured nearly unconditional Iranian and U.S. backing and purged professional officers in favor of incompetent loyalists. He intentionally pitted organs of the state and his hard-line Shiite Islamist constituency against all manner of opponents: Shiite secularists, Sunni Islamists, Sunni secularists, Kurds, and even rival Shiite Islamists.

Although Maliki achieved many successes during his first term, which coincided with Bush’s surge, his second, from 2010 to 2014, was catastrophic. Violence rose from the post-2003 lows to new heights. Entire divisions of the Iraqi army melted away in the face of vastly smaller forces, leaving billions of dollars’ worth of vehicles, weapons, and ammunition behind for use by terrorists. The entirety of Iraq’s Sunni heartland fell to the Islamic State. Baghdad’s relations with Iraqi Kurdi-stan and the Sunni provinces collapsed, and the central government lost control over more than half its territory. The Iranian-backed Shiite militias that Maliki had once crushed rebounded so ferociously in the face of the Islamic State’s assaults that they now likely outnumber the official Iraqi security forces. Most damning, both the Islamic State and the Shiite militias now wield advanced U.S. military hardware as they commit atrocities throughout Iraq.

Across much of the Middle East today, a sad truth prevails: decades of bad governance have caused richly diverse societies to fracture along ethno-sectarian lines. In Iraq, it is now evident that Shiite Islamists will not accept secular-nationalist rule by Sunnis or Shiites and that neither camp will accept rule by Sunni Islamists, especially the radical version espoused by the Islamic State. The relatively secular Kurds, meanwhile, are unwilling to live under Arab rule of any sort. In short, these powerful groups’ visions of life, religion, and politics are fundamentally incompatible. As for the minority Christian, Shabak, Yazidi, Sabean Mandaean, and Jewish communities that once numbered in the millions and occupied Mesopotamia for millennia, they have faced the Hobbesian fate of violent death or permanent displacement.

FROM BAD TO WORSE

Despite some tactical gains, such as the liberation of Tikrit, the strategic situation has only gotten worse since Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi succeeded Maliki in September 2014. Over the past year, the Islamic State has enhanced its position, even in the face of coalition bombing campaigns chronicled on Twitter by top U.S. officials, who, echoing General William Westmoreland during the Vietnam War, cite body counts and the number of air strikes as metrics for success. Mosul was taken by the Islamic State in June 2014; today, few are talking about liberating it anytime soon, and the terrorists have thrust forward to capture Ramadi, the capital of Iraq’s Anbar Province. The barbarians that Obama dismissed as the “JV team” are now a few dozen miles from the gates of Baghdad, as they expand their reach in Syria and establish franchises across Africa and Asia. Earlier this year, when I asked one of Iraq’s deputy premiers how Baghdad looked, he shrugged and said, “How should I know? I can’t leave the Green Zone.”

The collapse of the Iraqi security forces and the rise of the Shiite militias have weakened Baghdad’s already feeble grip on the country and empowered Tehran, since the militias have sworn allegiance to Iran’s supreme leader and are directed by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. U.S. military commanders have rightly voiced alarm over the growing strength and popularity of these terrorist groups, which are responsible for bombing U.S. and allied embassies and killing and maiming thousands of Iraqi, U.S., and coalition troops. Every time the militias thrust into Sunni enclaves, they carry out new atrocities and displace more people, inevitably enhancing the Islamic State’s appeal. Every time the Islamic State bombs innocent Shiite civilians, the Shiite militias grow stronger, and the Iraqi government grows weaker.

Compounding Baghdad’s nightmare has been the plunge in oil prices, which has left Abadi’s government with a budget deficit in the tens of billions of dollars, a limited ability to borrow on the international capital markets, and the prospect of looming stagflation. Youth unemployment has stayed chronically high. This past summer, with temperatures rising well above 120 degrees Fahrenheit and households having no more than a few hours of water and electricity per day, the seething population was primed to explode.

And that is precisely what happened. In July, tens of thousands of largely peaceful and secular protesters filled public squares across Baghdad and the provincial capitals of southern Iraq, decrying sectarianism, corruption, the lack of jobs, and nonexistent government services. Angrier protesters burned in effigy leading national politicians, namely Maliki, who was now one of Iraq’s three vice presidents yet still wielding power behind the scenes in a bid to undermine Abadi. Government offices in Maliki’s hometown were sacked, and crowds threatened violent action against the Basra-based international oil companies, Iraq’s only economic lifelines.

After Abadi announced limited reforms, Sistani, sensing mass unrest and a budding threat from rival clerics in Iran, instructed Abadi through his representatives’ weekly sermons to “be more daring and courageous.” In response, Abadi announced a series of major reforms, including the abolishment of the offices of the three deputy premiers and the three vice presidents, along with 11 of 33 cabinet posts. To overcome paralysis and hold officials accountable, Abadi promised to eliminate the ethno-sectarian quota system in the government and prosecute dozens of top civilian and uniformed leaders for corruption and dereliction of their duties in the face of the Islamic State’s assault.

In a rare show of unity, parliament unanimously adopted the measures on August 11. Mass rallies erupted in Baghdad, with protesters chanting, “We are all Abadi.” But Maliki and the other two vice presidents refused to step down, insisting that their positions were constitutionally mandated. And so the paralysis in Baghdad continued.

A week after the reforms were approved, Sistani issued a direct and dire warning. Iraq’s politicians had not served the people, and their misdeeds had enabled the rise of the Islamic State, he argued. “If true reform is not realized,” he said, Iraq could be dragged into “partition and the like, God forbid.”

So began the most recent chapter of the centuries-long intra-Shiite rivalry, as Sistani and Abadi battled Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his favored proxies in Iraq, namely, Maliki and the militia commanders, for control of Mesopotamia.

Although little noticed or understood in the West, and in a reminder than no major ethno-sectarian group can ever be monolithic, Shiite Arab and Shiite Persian rivalries have persisted for centuries, pitting Iraq’s Najaf seminary against Iran’s Qom establishment. At the time of this writing, Najaf’s Sistani is discreetly blasting Iran’s leading militia in Iraq, Kataib Hezbollah, for its alleged involvement in kidnapping 18 Turkish civilians and for its threat to target the U.S. ambassador to Iraq. Undeterred, Tehran is attempting to consolidate its gains over Arabia, where, as the former Iranian intelligence minister Ali Younesi declared in March, “Iran has become an empire . . . and its current capital is Baghdad.”

Given the hellish combination of regional proxy wars and conflict between Iraq’s Sunnis and Shiites and between its Arabs and Kurds—and within each group as well—the most dangerous era of modern Iraqi history may have only just begun.

It is hard to see how members of the feckless national political elite, who built their reputations by sowing ethno-sectarian hatreds, can satisfy impatient protesters in the coming months. Following decades of misrule under Saddam and Maliki, there is little reason to believe that a critical mass of pluralistic Iraqi nationalists remains to salvage the Iraqi national identity. The divisions now run too deep. As Massoud Barzani, president of the Kurdistan Region, once put it to me, “The Shia fear past repression, the Sunnis fear future repression, and we Kurds fear both.”

Image: Displaced people from the minority Yazidi sect, fleeing violence from forces loyal to the Islamic State in Sinjar town, walk towards the Syrian border, August, 2014. RODI SAID / REUTERS

Nor is there much reason to believe that Iraq can rid itself of the corruption that is ingrained in the very dna of the post-2003 order. Sunnis and Shiites, Arabs and Kurds, secularists and Islamists—whatever their disagreements, all have been united not by God but by greed. The insatiable lust for power and money evidenced by virtually every national leader I met during my more than 2,100 days of U.S. government service in Iraq still leaves me dazed: a Kurdish official’s $2 million Bugatti Veyron parked along several other supercars at his beachfront villa abroad, the private airplanes of a secretive Sunni financier with several cabinet members in his pocket, a junior Shiite Islamist official’s $150,000 Breguet wristwatch to complement his $5,000 monthly salary from the office of the prime minister. These are the small fish.

As one friend, a tireless but beleaguered Iraqi civil servant, put it to me early during the war, “Under Saddam Hussein, our ministers dreamt of stealing millions. If Saddam caught them, they were immediately executed. Only Saddam and his sons dared steal en masse. These people you Americans have brought to rule us—they’re stealing billions.” My friend earns about $500 per month, an average wage. Years after we visited the White House together, his home was accidentally bombed by U.S. aircraft, wiping out his family’s life savings. The Pentagon offered him no apology or reparations. His fiancée was then shot in the head by a passing foreign security convoy; she suffered permanent brain damage and paralysis. The son of a Sunni father and a Shiite mother, like millions of Iraqis of mixed descent, he fears kidnapping and murder by both the Sunnis of the Islamic State and the Shiites of the Iranian-backed death squads.

A SEPARATE PEACE

There is no question now that George W. Bush waged a poorly conceived and poorly executed war. There is also no question now that Obama precipitously and irresponsibly disengaged from Iraq after backing a divisive leader in Maliki. Washington’s Iraq policy failures have transcended administrations and parties. But the next president has a chance to do better.

In an ideal world, Abadi would survive the looming assassination and coup attempts, and the current Iraqi government would not only remain intact through 2017 but also become functional. Baghdad would mend the country’s ethno-sectarian divisions, slash corruption by prosecuting and jailing top officials (starting with senior judicial and cabinet figures), and reverse the advances of the Islamic State and the Shiite militias. If this somehow happens, Washington should reward Iraq’s leaders by continuing the Bush-Obama strategy of diplomatically backing a strong central government while providing military and counterterrorism assistance strictly conditioned on further reforms.

It is far more likely, however, that Iraq will continue its current slide and its government will keep failing to fulfill its basic obligations to deliver security and services. In that case, the next U.S. president should act decisively to prevent Iraq from degenerating into a second Syria, a zombie state terrorizing its citizens, exporting millions of refugees, and incubating jihad. This would mean openly encouraging confederal decentralization across Iraq and Syria—devolving powers from Baghdad and Damascus to the provinces while maintaining the two countries’ territorial integrity. In extreme circumstances, Washington might resort to embracing Balkan-style partition and a new regional political order.

Such a policy would represent a sharp departure for the U.S. national security establishment, which, among other things, has difficulty adapting to the unforeseen and dealing with nontraditional actors. Yet precisely because Washington’s traditional authoritarian counterparts have failed so spectacularly, it is nonstate actors that now dominate the Middle East. As a result, across the region, millions of youth have become disillusioned and radicalized, and extremists have exploited power vacuums to wage transnational jihad.

As it acknowledges the realities festering on the ground today, the United States will have to adopt an overarching strategy for the Middle East, one that goes far beyond Obama’s counterterrorism-focused approach. In Iraq and Syria, artificial borders have been erased, and the governments in Baghdad and Damascus have lost legitimacy in the eyes of millions of citizens. Because Washington can no longer deal with these governments as the exclusive representatives of their people, it will have to work with the world’s other great powers and the Middle East’s regional powers—Iran, Israel, Egypt, Turkey, and the Arab monarchies—to define new spheres of influence.

This process will be neither quick nor easy and will involve hundreds of delicate maneuvers. To begin with, however, the United States should work through the UN Security Council to launch a Middle East détente initiative that brings everyone to the table, much as Clinton convened various stakeholders in the Dayton peace talks to end the Bosnian war. Although it is not without risk, the strategy will rest on embracing the universal right to self-determination guaranteed by the UN Charter.

To that end, global and regional powers should agree on a new political order, try to broker cease-fires, deploy peacekeepers, and, as administrative and security conditions permit, allow every district in Iraq and Syria to conduct cascades of UN-monitored referendums. Although Iran may play a spoiler role and seek to preserve its ability to attack Israel by securing its land bridge across Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, it can eventually be neutralized by unanimous global pressure, as the recent nuclear deal demonstrated. Some Sunni powers will surely deploy their own dirty tricks in an attempt to predetermine outcomes; global powers must make it clear that there will be zero tolerance for such behavior and, more important, that they are prepared to inflict tangible pain if bad acts continue. They must also make it explicit that the civilized world is now at war with radical militant Islamists and that state sponsorship of these terrorists, whether Sunni or Shiite, will no longer be tolerated.

Under the present conditions, one can imagine that the Syrians would vote for rump Alawite, Christian, and Druze enclaves along the Mediterranean coast, one or more Sunni Arab governments across the heartland (which would rise up against the Islamic State in an Iraq-style “tribal awakening” should the appropriate campaign plan be adopted), and a semiautonomous Kurdish region in the north. The first would fall under the spheres of influence of Iran and Russia, while the latter two would fall under the Turkish, Arab, and Western spheres. No longer caught in the clutches of a genocidal dictator, Syria’s diverse and industrious population could begin to rebuild, just as the war-ravaged citizens of Germany, Japan, and Korea once did. To cement truth and reconciliation, the Security Council will have to guarantee mass amnesty, or, should the stakeholders agree, the International Criminal Court will need to start indicting perpetrators of war crimes from all factions in a bid to deter further bloodletting.

In neighboring Iraq, a nearly identical pattern has already emerged on the ground. The Shiite provinces would likely choose to form anywhere between one and nine regions; oil-rich Basra, for instance, has been threatening self-rule for a decade in the face of Baghdad’s failure to deliver security and services. The Sunni provinces would form between one and three regions and cleanse their territories of the Islamic State through a reinvigor-ated and internationally supported “tribal awakening.” And Iraqi Kurdistan would no doubt continue down the path toward economic self-sufficiency, leveraging the opportunity to export oil and gas to Turkey and the European Union. Special independent status could be granted to the diverse and geopolitically sensitive provinces of Baghdad, Diyala, and Kirkuk (à la the District of Columbia), in a last ditch effort at maintaining their pluralism. Unlike in Syria, in Iraq, many of these processes are already permitted by the constitution.

As Iraqi Kurdistan demonstrated during the 1990s, transitions to self-determination are often attended by regional interference, warlordism, corruption, cronyism, and internecine conflict. Nonetheless, as that case has also shown, with time—and with constant international rewards for good behavior and sanctions for bad behavior—self-determination always produces better results than authoritarianism. Were Saddam still terrorizing the Kurds today, a Kurdish insurgency would be raging stronger than ever. Instead, autonomous rule in Kurdistan, albeit far from perfect, has contributed to relative security and the development of basic infrastructure and economic opportunity. This should serve as a model for the rest of Iraq and Syria.

Indeed, those eager to destroy the Islamic State at any cost should remember that al Qaeda in Iraq was defeated not by the U.S. military and intelligence services, the Kurdish Pesh Merga, or Iranian proxies but by Sunni Arab Iraqis, who led the fight with international support. Likewise, al Qaeda in Iraq’s supercharged successor, the Islamic State, can never be defeated by air strikes or foreign boots on the ground alone. The Islamic State’s root cause—poor governance—is indigenous. Thus its root solution—good governance—must also be indigenous. Only local actors can break the vicious cycle of poverty, disenchantment, radicalization, and extremism and spark a virtuous cycle that offers security, jobs, education, moderation, dignity, and, most critically, hope that tomorrow will be better than today.

Barring a miracle, managed decentralization across Iraq and Syria may soon be the only viable path ahead. The next U.S. president could choose to respond to the inevitable crises there by following an ideological course, as his or her predecessors did, or attempt to manage them actively yet rationally. With or without Washington, a new reality is dawning on Mesopotamia.

In: foreignaffairs