Día: 21 marzo, 2018

Comisión de trabajo aprobó propuesta de pasar trabajadores a planilla

Pleno definirá futuro de Contrato Administrativo de Servicios (CAS). Medida costaría 0.4% del PBI. (USI)

Imagen: https://elcomercio.pe/economia/peru/regimen-contratacion-cas-balanza-cumple-objetivos-441060

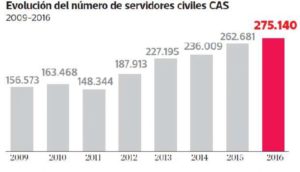

Una votación a favor por unanimidad en la Comisión de Trabajo del Congreso de la República generó que se aprobara la propuesta legislativa que plantea eliminar la modalidad de Contrato Administrativo de Servicios (CAS ) y, con ello, pasar a planilla a más de 500 mil trabajadores públicos que carecen de beneficios laborales.

“Con cargo a redacción, se ha votado (a favor) por unanimidad”, dijo el presidente del grupo de trabajo, Justiniano Apaza. De esta manera, el proyecto de ley quedará a la espera de ser debatido en el Pleno del Congreso.

AUSENTE

Cabe destacar que la sesión no contó con la presencia de la titular del Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas (MEF), Claudia Cooper , quien se esperaba que asistiera para dar a conocer la postura de su sector debido a que la aprobación de la iniciativa costaría al Estado cerca de S/2,178 millones y supondría el fin de la Ley del Servicio Civil (Servir).

En: peru21

Leer: El régimen de contratación CAS en la balanza ¿Cumple sus objetivos?

Peruvian President Resigns Amid Vote-Buying Scandal

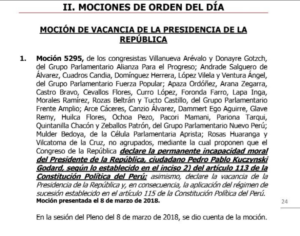

¿Qué se necesita para vacar a PPK?

El presidente Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (PPK) se presentará al Congreso y se votará para decidir si es que continuará en el cargo o si será vacado. No obstante, se ha discutido mucho sobre si el proceso se está llevando de forma adecuada o si lo que está habiendo es un golpe de Estado.

¿Qué se necesita para poder vacar al presidente?

En primer lugar, las causales de vacancia son las siguientes según la Constitución:

Artículo 113°.- La Presidencia de la República vaca por: 1. Muerte del Presidente de la República. 2. Su permanente incapacidad moral o física, declarada por el Congreso. 3. Aceptación de su renuncia por el Congreso. 4. Salir del territorio nacional sin permiso del Congreso o no regresar a él dentro del plazo fijado. Y 5. Destitución, tras haber sido sancionado por alguna de las infracciones mencionadas en el artículo 117º de la Constitución.

En este caso, quienes apoyan la moción de vacancia argumentan que PPK estaría en una situación de incapacidad moral permanente. Sin embargo, no hay claridad sobre cuándo un presidente es un incapaz moral y no debe seguir en su cargo, lo que da pie a muchísimas interpretaciones.

Ahora, el proceso de vacancia está regulado en el artículo 89-A del reglamento del Congreso.

-Para que se pueda hacer un pedido de vacancia (que ya se hizo) se requiere la firma de no menos del 20% del Congreso, más los fundamentos por los que se presenta la vacancia y documentos que acrediten esos fundamentos.

-Luego, el pedido debe aprobarse con, por lo menos, el 40% de los votos del Congreso. El pedido se aprobó con 93 votos a favor, lo que equivale aproximadamente al 67% de congresistas. Esta votación, según el reglamento, debe hacerse en la sesión siguiente a la que se presentó el pedido.

-Luego, se acuerda el día y hora para el debate y votación. Aquí lo importante. El reglamento dicta que esa sesión debe realizarse entre 3 y 10 días desde que se apruba la moción. Si las cuatro quintas partes del Congreso deciden que se haga en un plazo menor, pueden hacerlo, pero no puede extenderse el plazo. Por lo tanto, dentro de los 10 días necesariamente debe decidirse si el presidente será vacado o no.

Además, el presidente puede defenderse. Para ello, el reglamento le da un máximo de 60 minutos. “El Presidente de la República cuya vacancia es materia del pedido puede ejercer personalmente su derecho de defensa o ser asistido por letrado, hasta por sesenta minutos.”

-Para que el presidente sea vacado se necesita dos tercios del voto del número legal de congresistas, lo que equivale a 87 votos como mínimo.

“La resolución que declara la vacancia rige desde que se comunica al vacado, al Presidente del Consejo de Ministros o se efectúa su publicación, lo que ocurra primero.”

Por: Renán Ortega

Editor Altavoz

@rortegaolivera

En: altavoz.pe

Kate Steinle murder trial: How the prosecution’s case fell apart

A jury’s near-full acquittal in the Pier 14 killing of Kate Steinle shocked many people who expected a conviction for murder or at least manslaughter. After all, there was no dispute that the accused man held the gun that fired the fatal bullet and that he hurled the weapon into San Francisco Bay as Steinle lay dying.

But the prosecution was, in some ways, fighting uphill from the start, legal experts said Friday, one day after Jose Ines Garcia Zarate was convicted only of a single count of being a felon in possession of a firearm.

“You have to prosecute a case with the evidence you have, and that’s what the prosecution did,” said Hadar Aviram, a criminal law professor at UC Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco. “I think in this case, there just wasn’t the evidence.”

City authorities never overcame a critical obstacle and established a motive that would explain why the 45-year-old homeless undocumented immigrant — whose release from San Francisco jail before the shooting under the city’s sanctuary policies became a national controversy — would want to kill a stranger.

And though prosecutors believed Garcia Zarate brought the semiautomatic pistol to the waterfront on July 1, 2015, they had little evidence to counter the defense assertion that he found the gun in a T-shirt or cloth and picked it up, causing it to fire accidentally. The gun had been stolen four days earlier from the nearby parked car of a federal ranger, but the burglary remains unsolved.

The defense had little evidence supporting its account, either, but the burden was on the prosecution to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

President Trump called the verdict “a complete travesty of Justice” on Friday and — echoing of a number of conservative pundits — suggested that the jury should have been told that Garcia Zarate “came back and back over the weakly protected Obama border, always committing crimes and being violent.”

But while Garcia Zarate has been deported five times and has drug convictions in the U.S., he has no violent convictions. And evidence of prior criminal history — and by extension, poor character — is generally not admissible in U.S. courts, unless it is directly relevant to the current case.

Garcia Zarate was charged with murder from the beginning, and prosecutors gave jurors three options.

They could convict on first-degree or premeditated murder. They could opt for second-degree murder, requiring a finding that Garcia Zarate either intended to kill Steinle or intentionally committed a dangerous act with conscious disregard for human life. Or they could choose involuntary manslaughter, which would require a finding that Garcia Zarate caused Steinle’s death with an unlawful, negligent act.

To prove murder, Assistant District Attorney Diana Garcia needed to convince jurors that the round that killed Steinle had been fired intentionally. But this was a difficult task as the bullet first struck the pier’s concrete 12 to 15 feet from Garcia Zarate, then bounced and traveled 78 more feet to strike Steinle in the back as she strolled with her father.

“The evidence that Kate Steinle was killed with a ricochet shot, rather than a direct shot, makes it even tougher to prove to the jury beyond a reasonable doubt that it was an intentional killing,” said attorney Jim Hammer, a former city prosecutor.

Throughout the trial, attorney Matt Gonzalez of the public defender’s office sought to characterize the ricochet as proof that Steinle’s death had been a tragic accident that befell a hapless man.

With no direct accounts from eyewitnesses or surveillance video showing Garcia Zarate’s actions during the shooting and in the moments just before, what remained were dueling conclusions drawn from circumstantial evidence.

And in California, the law on circumstantial evidence swings in the defense’s favor. Jurors are instructed that if they “can draw two or more reasonable conclusions from the circumstantial evidence, and one of those reasonable conclusions points to innocence and another to guilt, you must accept the one that points to innocence.”

“That’s a tough hurdle for a prosecutor to overcome,” Hammer said. “I think for those who are outraged by this verdict, they have to remember that the defense didn’t have to prove that it was an accident. All they had to do was raise reasonable doubt and that there was some other reasonable scenario.”

Jurors declined requests to explain their thinking as they left the city courthouse Thursday.

Garcia offered evidence that the pistol that killed Steinle would fire only with a firm pull of the trigger. She pointed at the defendant’s actions after the shooting — tossing the firearm and walking away — as an implication of guilt. The prosecutor called to the stand a crime scene inspector, who testified that he believed Garcia Zarate had to have aimed the gun toward Steinle for the bullet to have followed the path that it did.

And she played clips of Garcia Zarate’s four-hour police interrogation for the jury. But his alleged confession included a variety of stories about what happened, some conflicting with each other and physical evidence.

Garcia Zarate’s attorneys attacked the interrogation, and they countered as well by calling an expert who testified it was unlikely that such a ricochet shot was intentional. They contended that Garcia Zarate tossed the gun in the bay because he was frightened.

“We have to deduce how a stranger was thinking at the time of the crime from various external evidence,” Aviram said. “It’s not a question of who the jurors believe more. They have to be very close to 100 percent certain that he had intent in order to convict. And they were not.”

It’s unclear whether the prosecution’s trial strategy backfired. Garcia spent most of the trial laying the groundwork for a second-degree murder charge, but in her closing remarks, she introduced a possible motive in a bid for first-degree murder, saying Garcia Zarate had been “playing his own secret version of Russian roulette” when he brought a loaded firearm to a “target-rich environment.”

However, throughout the six-week trial the prosecutor presented little evidence to support that theory, only calling to the witness stand a tourist who was at the pier the day of the shooting and who testified that Garcia Zarate gave her an uneasy feeling.

In his closing arguments, Gonzalez said the case should not have been charged at all, hinting that the political uproar caused by Garcia Zarate’s immigration status had pushed prosecutors — who deny the claim — to seek a harsher punishment.

“Prosecutors don’t always pursue cases in which they’re certain of the outcome,” Aviram said.

Alex Bastian, a spokesman for the district attorney’s office, said the case “made its way to a trial courtroom for a reason. … At every stage, there was sufficient evidence.”

Hammer noted that the jury spent six days in deliberations, suggesting their decision was not rushed and that they carefully weighed the evidence.

“You may not like the outcome, but if you put 12 strangers into a room and they all agree on something, you need to respect that,” Hammer said. “I don’t think it was an easy decision. I think they knew they were going to walk out and get criticized. But they were the 12 who had that responsibility, and that was what they did.”

Garcia Zarate is scheduled to return to court Dec. 14, and when he is sentenced faces up to three years in state prison — a term he has likely already satisfied since his arrest. Federal authorities on Friday unsealed a warrant for his arrest related to his immigration status, and plan to deport him for a sixth time.

Vivian Ho is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: vho@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @VivianHo