Livingstone v. Evans et al

Livingstone

v.

Evans et al

Alberta Supreme Court, Trial

Walsh, J.

October 30, 1925

Walsh, J.:

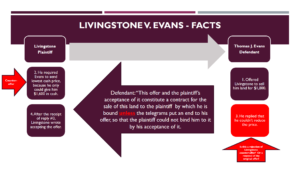

The defendant, Thomas J. Evans, through his agent, wrote to the plaintiff offering to sell him the land in question for $1,800 on terms. On the day that he received this offer the plaintiff wired this agent as follows: “Send lowest cash price. Will give $1,600 cash. Wire.” The agent replied to this by telegram as follows: “Cannot reduce price.” Immediately upon the receipt of this telegram the plaintiff wrote accepting the offer. It is admitted by the defendants that this offer and [770] the plaintiff’s acceptance of it constitute a contract for the sale of this land to the plaintiff by which he is bound unless the intervening telegrams above set out put an end to his offer so that the plaintiff could not thereafter bind him to it by his acceptance of it.

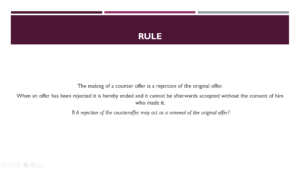

It is quite clear that when an offer has been rejected it is thereby ended and it cannot be afterwards accepted without the consent of him who made it. The simple question and the only one argued before me is whether the plaintiff’s counter offer was in law a rejection of the defendant’s offer which freed him from it.

Hyde v. Wrench (1840) 3 Beav. 334, 49 E.R. 132 a judgment of Lord Langdale, M.R. pronounced in 1840 is the authority for the contention that it was. The defendant offered to sell for £1,000. The plaintiff met that with an offer to pay £950 and (to quote from the judgment) “he thereby rejected the offer previously made by the Defendant. I think that it was not afterwards competent for him to revive the proposal of the Defendant, by tendering an acceptance of it.”

Stevenson v. McLean, (1880) 5 Q.B.D. 346, a later case relied upon by Mr. Grant is easily distinguishable from Hyde v. Wrench as it is in fact distinguished by Lush, J. who decided it. He held that the letter there relied upon as constituting a rejection of the offer was not a new proposal but a mere enquiry which should have been answered and not treated as a rejection but the learned Judge said that if it had contained an offer it would have likened the case to Hyde v. Wrench.

Hyde v. Wrench has stood without question for 85 years. It is adopted by the text writers as a correct exposition of the law and is generally accepted and recognized as such. I think it not too much to say that it has firmly established it as a part of the law of contracts that the making of a counter-offer is a rejection of the original offer.

The plaintiff’s telegram was undoubtedly a counter-offer. True, it contained an inquiry as well but that clearly was one which called for an answer only if the counter-offer was rejected. In substance it said, “I will give you $1,600 cash. If you won’t take that wire your lowest cash price.” In my opinion it put an end to the defendant’s liability under his offer unless it was revived by his telegram in reply to it.

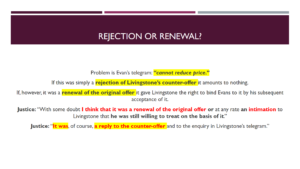

The real difficulty in the case, to my mind, arises out of the defendant’s telegram “cannot reduce price.” If this was simply a rejection of the plaintiff’s counter-offer it amounts to nothing. If, however, it was a renewal of the original offer it [771] gave the plaintiff the right to bind the defendant to it by his subsequent acceptance of it.

With some doubt I think that it was a renewal of the original offer or at any rate an intimation to the plaintiff that he was still willing to treat on the basis of it. It was, of course, a reply to the counter-offer and to the enquiry in the plaintiff’s telegram. But it was more than that. The price referred to in it was unquestionably that mentioned in his letter. His statement that he could not reduce that price strikes me as having but one meaning, namely, that he was still standing by it and, therefore, still open to accept it.

There is support for this view in a judgment of the Ontario Appellate Division which I have found, In re Cowan and Boyd (1921), 61 D.L.R. 497, 49 O.L.R. 335. That was a landlord and tenant matter. The landlord wrote the tenant offering a renewal lease at an increased rent. The tenant replied that he was paying as high a rent as he should and if the landlord would not renew at the present rental he would like an early reply as he purposed buying a house. To this the landlord replied simply saying that he would call on the tenant between two certain named dates. Before he called and without any further communication between them the tenant wrote accepting the landlord’s original offer. The County Court Judge before whom the matter first came held that the tenant’s reply to the landlord’s offer was not a counter-offer but a mere request to modify its terms. The Appellate Division did not decide that question though from the ground on which it put its judgment it must have disagreed with the Judge below. It sustained his judgment, however, on the ground that the landlord’s letter promising to call on the tenant left open the original offer for further discussion so that the tenant had the right thereafter to accept it as he did.

The landlord’s letter in that case was, to my mind, much more unconvincing evidence of his willingness to stand by his original offer in the face of the tenant’s rejection of it than is the telegram of the defendant in this case. That is the judgment of a very strong Court, the reasons for which were written by the late Chief Justice Meredith. If it is sound, and it is not for me to question it, a fortiori must I be right in the conclusion to which I have come.

I am, therefore, of the opinion that there was a binding contract for the sale of this land to the plaintiff of which he is entitled to specific performance. It was admitted by his counsel that if I reached this conclusion his subsequent agreement [772] to sell the land to the defendant Williams would be of no avail as against the plaintiff’s contract.

There will, therefore, be judgment for specific performance with a declaration that the plaintiff’s rights under his contract have priority over those of the defendant Williams under his. […]

Judgement for the plaintiff.

In: h2olawharvard