A reporter pressed the White House for data. That’s when things got tense.

Wednesday’s White House news briefing began not with press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders but with senior adviser Stephen Miller, whose nationalist immigration positions have been highly influential in the administration. Miller was at the lectern to discuss the Raise Act, legislation crafted by Sens. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) and David Perdue (R-Ga.) and introduced by President Trump earlier in the day.

During his brief stint addressing the White House press corps, Miller got into two serious arguments with reporters, an impressive if not surprising accomplishment. One, with CNN’s Jim Acosta, included accusations of Acosta having a “cosmopolitan bias” in his thinking about immigration. (Worth noting: Acosta is the son of immigrants.) But the other, a dust-up with the New York Times’ Glenn Thrush, was more significant.

Before getting into that, though, it’s worth isolating part of Miller’s introduction to the topic, the sentence that formed the crux of his rhetoric in defense of a bill that will slice legal immigration in half if it is enacted into law.

“You’ve seen over time as a result of this historic flow of unskilled immigration,” Miller said, “a shift in wealth from the working class to wealthier corporations and businesses, and it’s been very unfair for American workers, but especially for immigrant workers, African American workers and Hispanic workers, and blue-collar workers in general across the country.”

That line does two things that are essential to Miller’s sales pitch. First, it blames income inequality — assuming that money headed to “wealthier corporations” means to those corporations’ owners — on increased immigration. Second, it highlights the effects on black, Hispanic and immigrant workers in particular.

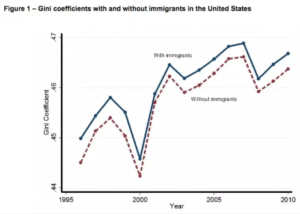

There has been research that links increased income inequality to immigration. A 2015 paper by a trio of researchers found just such a link. But assuming that link, it’s clearly not the only — or even the primary — driver of income inequality. A graph created by those researchers makes clear that the inequality (as measured with the Gini coefficient) would be nearly as high without the effects of immigration.

Image: https://img.washingtonpost.com/wp-apps/imrs.php?src=https://img.washingtonpost.com/news/politics/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2017/08/Screen-Shot-2017-08-02-at-4.30.41-PM.png&w=1484

The effect of immigrants, the researchers say, is “modest.” But Miller presents the “shift in wealth” as being a “result” of the flow of unskilled immigrants. In other analyses of that increased gap, immigration isn’t mentioned.

Miller’s suggestion that those most affected by this shift are other communities of color, meanwhile, is a classic tactic aimed at appealing to working-class Americans and nonwhite voters by blaming immigrants for their problems. (Hillary Clinton did something similarduring a debate in the 2008 primaries.)

When Miller began to take questions, Thrush asked him very specifically for data to back up his points.

THRUSH: First of all, let’s have some statistics. There have been a lot of studies out there that don’t show a correlation between low-skilled immigration and the loss of jobs for native workers. Cite for me, if you could, one or two studies with specific numbers that prove the correlation between those two things, because your entire policy is based on that. …

MILLER: I think the most recent study I would point to is the study from George Borjas that he just did about the Mariel Boatlift. And he went back and reexamined and opened up the old data and talked about how it actually did reduce wages for workers who were living there at the time.

And Borjas has, of course, done enormous amounts of research on this, as has the — Peter Kirsanow on the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, as has Steve Camarota at the Center for Immigration Studies, and so on and so on.

We’ll jump in here first to note that Miller offered no statistics but did point to one study.

That study from Borjas looked at the migration of more than 100,000 Cubans into Florida in 1980. Borjas found that wages among the least-educated workers in Miami dropped 10 to 30 percent as a result of the influx. Borjas’s study was a direct rebuttal to a 1990 study by David Card, which found “virtually no effect” on wages or unemployment rates, even among the Cuban immigrant community that was already in the area.

Borjas’s study was itself soon rebutted, as the National Review noted, with researchers pointing out that he didn’t account for other demographic shifts in the area that may have had a significant effect on wages.

Miller also notes two other individuals, one of whom works for the staunchly anti-immigration Center for Immigration Studies — and then implies a surfeit of other data with a casual “and so on, and so on.”

THRUSH: What about the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine? …

MILLER: One recent study said that as much as $300 billion a year may be lost as a result of our current immigration system, in terms of folks drawing more public benefits than they’re paying in.

Thrush raises a recent study showing that immigrants don’t take the jobs of native-born Americans, with the exception of teenagers who didn’t finish high school, who saw a drop in hours of work.

Miller responds by noting that the study also found that new immigrants cost nearly $300 billion a year more in government spending than they pay in taxes — though that’s the far end of a spectrum of estimates that starts at $43 billion. By the second generation, immigrant families add a net of $30 billion a year.

Then things got tense.

MILLER: But let’s also use common sense here, folks. At the end of the day, why do special interests want to bring in more low-skill workers? And why, historically …

THRUSH: I’m not asking for common sense. I’m asking for specific statistical data. How many …

MILLER: Well, I think it’s very clear, Glenn, that you’re not asking for common sense. But if I could just answer — if I could just answer your question …

THRUSH: Common sense is fungible, statistics are not.

MILLER: … I named — I named — I named the studies, Glenn.

THRUSH: Let me just finish the question …

MILLER: Glenn. Glenn.

THRUSH: Tell me the …

MILLER: I named the studies. I named the studies.

Again: He named one study. At this point, it got personal.

THRUSH: I asked you for a statistic. Can you tell me how many — how many …

MILLER: Glenn. The — maybe we’ll make a carve-out in the bill that says the New York Times can hire all the low-skilled, less-paid workers they want from other countries and see how you feel then about low-wage substitution. …

You know, maybe it’s time we had compassion, Glenn, for American workers. President Trump has met with American workers who have been replaced by foreign workers.

THRUSH: Stephen, I’m not questioning any of that. I’m asking …

MILLER: And ask them — ask them how this has affected their lives.

The exchange went on in this vein for a while, with Miller ultimately pointing not to statistical data showing a need for the policy but to general statistics about unemployment.

Ultimately, Miller again asked Thrush to set aside his request for data and to consider common sense.

“The reality is that if you just use common sense — and, yes, I will use common sense,” Miller said, “the reason why some companies want to bring in more unskilled labor is because they know that it drives down wages and reduces labor costs. Our question as a government is, to whom is our duty? Our duty is to U.S. citizens and U.S. workers, to promote rising wages for them.”

That raised an obvious question, which other reporters subsequently jumped on: Why do Trump’s private businesses continue to seek visas allowing them to hire immigrants for low-wage jobs?

“I’ll just refer everyone here today back to the president’s comments during the primary, when this was raised in a debate,” Miller replied, “and he said: ‘My job as a businessman is to follow the laws of the United States. And my job as president is to create an immigration system that works for American workers.’ ”

It’s just common sense.

Emma Lazarus Poem at Statue of Liberty. Image: http://patriotretort.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Only-a-poem.jpg

In: washingtonpost