Legal reform: Judging judges

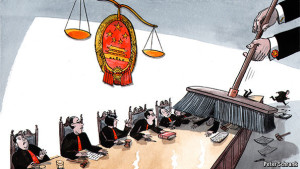

To help build “the rule of law”, China is demoting judges

Image: http://cdn.static-economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/full-width/images/print-edition/20150926_CND001_0.jpg

“I WAS tired of it. I did not like the pressure, so I chose freedom.” This is how a former Chinese judge describes his decision to quit as president of a provincial court and take up a new job in academia. It would have helped if he had earned more. A judge with years of court experience makes as much as a well-paid college graduate—a fraction of what a lawyer could earn, or a law professor who does freelance work on the side. Hence many of China’s best-qualified court officials are quitting. The government, eager to show that it is building “rule of law”, is struggling to stop the haemorrhage.

Official statistics would seem to suggest that China is not short of judges. There are said to be around 200,000 of them, or more than 14 per 100,000 inhabitants. Each Chinese court has an average of around 60. By comparison, litigious America has 11 judges per 100,000 citizens. But in China many of those described as judges work in administrative roles, and many do not have law degrees. Well-qualified judges have thus found their caseloads soaring—but not their pay. They still earn the same as back-office colleagues who also, inappropriately, enjoy the title of judge. To the chagrin, no doubt, of some, President Xi Jinping’s fierce campaign against corruption, launched when he came to power three years ago, has reduced opportunities for taking backhanders.

Mr Xi’s anti-graft drive is part of a campaign to convince a cynical public that the Communist Party is bound by the law and wants it to be applied fairly. To achieve this, he is trying to reform the courts to allow justice to be dispensed more swiftly and impartially. Officials have been threatened with punishment if they interfere with cases. The pay of proper judges will be boosted substantially. The size of the increase has not been made public, but it is expected to be at least 50% at first. And their status will, in effect, be enhanced by downgrading the titles of lesser judges.

Not so easy

At a meeting of court officials in July, a deputy chief of the Supreme Court, Shen Deyong, said there would be “a series of challenges and difficulties” in implementing reforms. But he said that targets for sifting the ranks of judges would be strictly enforced. He ordered courts to begin evaluating their staff to see who should make the grade. In Shanghai, courts have been ordered to retain only a third of their judges. The rest are to be given new, more fitting, titles, such as “legal assistant” and “administrative officer”.

Given the heavy-handed way Mr Xi has tightened his personal grip on the levers of power, suppressed the media and intimidated independent lawyers, it is easy to doubt his commitment to the rule of law. But Susan Finder, an expert on China’s legal system based in Hong Kong, says that the reforms are nonetheless making a difference. The majority of court cases, she notes, do not touch on politically sensitive issues of the kind that independent lawyers often like to take up, such as abuses of power by local officials. It is therefore possible to improve the judiciary (not least in the eyes of the public) without threatening the party’s grip on power.

In political cases, few doubt the party will continue to put its thumb on the scales of justice. It does this through “political and legal committees” which co-ordinate the work of the police, prosecutors and judiciary at every level. The power of these committees reached a peak under Zhou Yongkang, who was the leader of the party’s most powerful body of this kind between 2007 and his retirement in 2012. Despite the recent sentencing of Mr Zhou to life imprisonment in a sensational corruption case, there is no sign that Mr Xi wants to abolish the committees—even if he would like to reduce their involvement in the decision-making of courts.

In civil and commercial cases, officials often interfere to protect their own interests, or those of friends or family. This causes much public resentment and is the main reason why thousands of petitioners head to Beijing every year to seek redress from the central government—a potential cause of social unrest that alarms the authorities. Last month measures were enacted that prohibit courts from heeding requests from “any organisation or individual” that would impede judicial fairness. Courts must now record and report promptly and fully on such requests, even oral ones, “so that the entire process leaves a trail, permanently preserved”.

To shield courts further from interference, responsibility for judges’ salaries and job assignments will shift from governments at the same level to higher-level ones. These are considered less likely to have a stake in the verdicts.

The reforms should greatly improve the working environment for those judges who keep their titles, as should the increase in salaries. That they are urgently needed is evident: in Shanghai alone, according to state media, 86 judges resigned last year—half of them with advanced degrees in law. The majority were younger judges who were among the system’s most highly prized. Between January and the end of March, another 18 had quit, amid double-digit growth in the number of cases being handled by the city’s courts.

As the title adjustments get under way, those who fail to make the cut will face a difficult choice: stay on with their diminished status or seek employment elsewhere. Coming out on the losing end of the evaluation process may not be a stellar credential. But the value of their powerful connections should still be worth something in the job market.

From the print edition: China

In: economist.com