The China Factor in America’s State and Local Economies

As the world’s second-largest economy falters, pensions and tax revenues here are feeling the pinch.

BY LIZ FARMER | AUGUST 2016

Earlier this summer, New York state’s pension fund announced a mediocre year. Investment earnings were essentially flat, and as a result the fund lost $5 billion because its other receipts — contributions from government and from current employees — didn’t cover retiree payouts.

The New York pension system was the victim of a global event that began halfway across the world a year ago this month. In August 2015, the world’s second-largest economy officially began to stumble. China’s central bank stunned investors by devaluing the yuan, lending credence to what outsiders had long been suspecting: China’s years of astounding annual economic growth — at times cresting at double digits — was slowing down.

Toward the end of that month, China’s stock market endured its biggest one-day fall since 2007. The state media dubbed it “Black Monday” and the result shocked the world. Emerging market currencies slumped, commodity prices fell and Western financial markets reeled. At one point, General Electric’s stock was down by more than 20 percent. The markets seemed to recover just in time for a January report from China that the country’s growth rate for 2015 — 6.9 percent — was the weakest in a quarter-century. Although robust by U.S. standards — GDP growth in the United States last year was 2.4 percent — the bad news from Beijing once again sparked market volatility here and abroad.

In short, China has made it a difficult year for institutional investors, public pension plans prominent among them. But financial markets aren’t the only way China’s economy can impact states and localities.

For the last decade, with China a reliable engine for economic growth, other countries around the world have been feeding off it. China is the leading destination for a handful of states’ exports and accounts for more than $115 billion in goods shipped annually from the U.S. The country is a key consumer of U.S.-made airplanes, cars and medical equipment. Meanwhile, Chinese companies have stepped up their investment in U.S. cities and industries, building auto plants, investing in oil fields and buying real estate — a Beijing-based company now owns the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York. There is essentially no region in the U.S. without some connection to China, and at least some vulnerability to a downdraft.

U.S. economists and state development officials are familiar with the ways negative economic events in Europe, such as Britain’s recent vote to leave the European Union, can have an effect here at home. And for the near future, events in Western Europe and some other developed powers, such as Japan, will continue to have the greatest impact on states and localities. But if things in China worsen, the economic pain for governments in this country could be severe.

Even before China’s crisis rattled the U.S. stock market, state and local pension plans were struggling. Last year, annual investment returns were meager. Because of the 2015 market plunge in China, most pension plans in the United States will likely report even worse returns for 2016. The two-year hit, says a Moody’s Investors Service analysis, will effectively wipe out the funding improvements seen in 2013 and 2014.

Under Moody’s most optimistic scenario, according to which U.S. investment returns average 5 percent for this year, overall pension plan liabilities will increase by 10 percent. Under the credit rating agency’s most pessimistic outlook, where investment losses are 10 percent for the year, Moody’s sees liabilities growing by more than half. In that case, governments would be faced with demands to put significantly more general fund money into pension plans than was previously forecast.

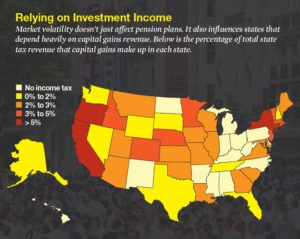

Market volatility doesn’t just affect pension plans. A number of state governments find their tax base is significantly exposed when investment income — capital gains revenue — has a bad year. California, Connecticut and New York all tend to “get clobbered” when financial markets have a down year, says Donald Boyd, the Rockefeller Institute of Government’s fiscal studies director. These three states and Oregon (which banks heavily on personal income tax payments in general), have the highest reliance in the nation on capital gains revenue. “If you have a lot of rich people and you tax them relatively heavily,” Boyd says, “then you’re going to be most affected by this kind of scenario.”

While there’s unlikely to be anything like the 20 percent revenue drops seen during the U.S. financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, states are already starting to feel the revenue impact of the past year’s stock market reactions to China’s slowdown. Income tax collections make up about one-third of the average state’s total revenue. In April, the single biggest income tax collection month for states, the average state’s income tax revenue was down nearly 10 percent from the previous year, according to a Reuters analysis.

It’s a taste of what could happen if China falters further. California had to trim its overall income tax revenue expectations for the 2016 fiscal year by nearly $2 billion, thanks to an April shortage of about $1 billion in collections. Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Pennsylvania also announced declines in actual or projected income tax receipts after April.

What made this issue doubly challenging was that the news came in around the time state lawmakers were in the midst of the tricky business of drawing up the next year’s budgets. “This throws a monkey wrench into it,” Boyd says, noting that it creates future problems as well. “When you’re dealing with a budget shortfall with only a few weeks to go in the fiscal year, there’s a good chance lawmakers aren’t going to find some kind of [permanent] solution. So that sets them up a year down the road for more trouble.”

Over the past decade, states and localities have jumped at chances to increase their business with fast-growing China. U.S. merchandise exports to China increased by 177 percent between 2005 and 2015. Chinese investment in U.S. companies and properties went up exponentially over the same time period, from $2.5 billion in total investment across 24 states to nearly $63 billion spread over all but three states.

Admittedly, the growth represents only a tiny slice of overall U.S international business. Exports to China account for less than 8 percent of overall outbound U.S. shipments. Chinese foreign direct investment totals less than 1 percent of all foreign investment here.

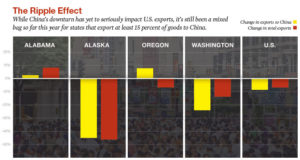

Some regions, however, have more established business ties. When it comes to exports, Washington state-based businesses are by far the most exposed to fluctuations in China. Last year, Washington businesses exported $19.4 billion in goods to the Asian nation — about one-fifth of all the state’s exports. Over the past year, Washington’s dealings with China have been ratcheting down. Last year saw a 5 percent drop in exports to China; data through May of this year shows exports to China down by about 25 percent. Robert Hamilton, Gov. Jay Inslee’s trade adviser, says trade activity is being driven down from weak economies “everywhere — not just China.” Indeed, overall U.S. exports fell 5 percent last year, the largest decrease since the recession.

Still, Washington state’s exposure creates some concerns. Trade directly and indirectly accounts for one out of every four jobs in the state. Last year, Moody’s flagged it for being an at-risk state thanks to a slower China. This year, Moody’s has been careful not to sound apocalyptic about Washington state’s situation. “They’re pretty well insulated,” says Moody’s Washington analyst Kenneth Kurtz. But China-watchers in the state remain nervous.

Other regions in the U.S. will see an impact if China’s demand for consumer products wanes significantly. Computer equipment, for example, is a top export to China. Companies based in San Jose, Calif.; Boise, Idaho; and Austin, Texas, are the nation’s top producers of those products, and will feel a pinch if Chinese shoppers stop buying. Detroit and other regions reliant on auto manufacturing could also see a dip in business if China’s high demand for U.S.-made cars slows.

Chinese investment in the United States has grown rapidly over the past decade, although it has been concentrated on a limited number of targets. The vast majority of the investments from China have been in mergers and acquisitions. These ownership changes tend to grab headlines — like when Chinese insurance giant Anbang bought the Waldorf from the Hilton hotel chain for nearly $2 bllion last year. In most cases, new Chinese ownership does not change a company’s economic footprint. Hilton, for example, remains the Waldorf’s operator.

One other area where Chinese investment has had an impact is in so-called greenfield purchases. Those are investments where the parent company builds its operations here from the ground up, such as Yuhuang Chemical’s $1.85 billion methanol plant in Louisiana or Tranlin Paper’s $2 billion paper plant in Virginia, both of which broke ground last year. In the San Francisco Bay Area, which has long been a favorite of Chinese companies, more than one-quarter of greenfield investment value in the region comes from China, according to the Brookings Institution’s Joseph Parilla. Other top areas in the country for greenfield purchases are Chicago, New York City, San Jose and Seattle.

Most greenfield investments are typically made with a long-term view, so a Chinese slowdown like the current one might not have much immediate effect on them. It’s possible that a slower economy at home could cause Chinese companies to direct more new investment toward stable economies like the United States and away from riskier markets in emerging countries. But it’s also possible that a weaker economy at home could force Chinese investors to pull back in all world markets as foreign development becomes a more expensive proposition than the country’s corporations want to make.

From time to time, there are fears about a local real estate market in the United States “being gobbled up” by the Chinese and other private global investors. “If they all pull back, then all of a sudden, you’ve got this glut of really high-end real estate built for folks who are not necessarily in your metro area,” Parilla says, adding that this is something to watch in New York City and San Francisco, and to a lesser extent Chicago and Seattle.

For now, China is a lesson in perspective. Long isolated from the rest of the world, it has taken advantage of its rapid growth and fast-growing connections to other countries to become a major force in global markets. As state and local governments in the United States have become more enmeshed with the Chinese economy, opening offices in China to attract more direct development, they have increased their exposure. Fears about the effects of a prolonged Chinese downturn played a big role in the psychological contagion that roiled U.S. financial markets last year.

So far, most of the negative fallout in this country has been confined to a limited number of regions and economic sectors. But if the Chinese economy remains sluggish for a long period, the effects will be felt much more broadly by American investors and state and local governments. That is why even governments that haven’t felt the effects so far may want to train a wary eye on the fiscal picture in Beijing.

In: governing