Los especialistas en temas de energía estaban emocionados por el desarrollo del gas natural extraído de las capas de esquisto casi cerca de todos lados. La aventura que comenzó y se expandió rápidamente por estados unidos de Norteamérica, y ha sido tal su avance que ha presionado los precios a la baja. De acuerdo 2Lead – The Sustainabilty Mulipliers Organization la compañías de gas rusa Gazprom canceló sus actividades en el ártico porque dados los precios ya no era rentable hacerlo.

Los reparos al desarrollo de esta nueva industria han legado por el lado de los prejuicios y dudas respecto a sus efectos contaminantes, o incluso sísmicos, o han provenido de los promotores de las energías renovables. En cualquier caso hasta el estudio conducido por Robert Jackson de la Universidad de Duke en Pensilvania, la contaminación no estaba comprobada, ahora si.

Reservas importantes de este gas hay en México y Argentina en latinoamérica. Y en ambos países hay proyectos en curso.

Scientific American ha publicado un artículo mostrando las evidencias de contaminación. Los investigadores descubrieron metano en 51 de los 60 pozos de prueba-algo que no esta fuera de lo común. Una pequeña cantidad de metano procedente de fuentes profundas está presente en la mayoría de los acuíferos de esta región de Pennsylvania y Nueva York. Pero los investigadores comprobaron que en los pozos cercanos a la perforación la cantidad de metano no solo era bastante mayor a lo “normal”, sino que por su composición era claro que provendría de la explotación gasífera.

Todo parece indicar que el juego en Nueva York (ver artículo) alrededor de la explotación del gas natural (como si el otro no lo fuera) en ese estado se detendrá por un tiempo, hasta que las autoridades tomen decisión sobre las prevenciones necesarias, y las medidas de monitoreo. Hasta dónde llegará el asunto, cuál será el efecto sobre los precios y por cuánto tiempo, es algo que todavía no podemos predecir.

Para más detalle aquí el artículo en inglés:

Hydraulic Fracturing for Natural Gas Pollutes Water Wells. A new study indicates that fracturing the Marcellus Shale for natural gas is contaminating private drinking water wells

By David Biello

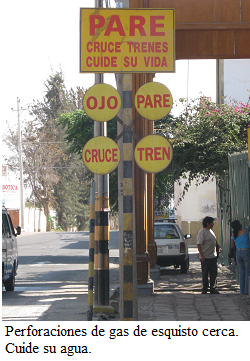

HYDRAULIC FRACTURING: A new technique for releasing natural gas in shale rock has contaminated at least some drinking water wells in Pennsylvania and New York State.

Drilling for natural gas is booming in Pennsylvania—thanks to fracturing shale rock with a water and chemical cocktail paired with the ability to drill in any direction. Despite homeowner complaints, however, research on how such hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is impacting local water wells has not kept pace. Now a new study that sampled water from 60 such wells has found evidence for natural gas–contamination in those within a kilometer of a new natural gas well.

“Methane concentrations in drinking water were much higher if the homeowner was near an active gas well,” explains environmental scientist Robert Jackson of Duke University, who led the study published online May 9 inProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “We wanted to try and separate fact from emotion.”

The researchers discovered methane in 51 of the 60 wells tested—that is not out of the ordinary. A small amount of methane from both deep and biological sources is present in most of the aquifers in this region of Pennsylvania and New York State. By measuring the ratio of radioactive carbon present in the methane contamination, however, the researchers determined that in drinking water wells near active natural gas wells, the methane was old and therefore fossil natural gas from the Marcellus Shale, rather than more freshly produced methane. This marks the first time that drinking water contamination has been definitively linked to fracking.

In fact, concentrations were 17 times higher in those drinking water wells within one kilometer of an active natural gas well than those farther away. Also, average methane concentrations of 19 milligrams of methane per liter in those wells were well above the10-milligram- per-liter recommendation (pdf) set by the U.S. Department of the Interior for action to reduce concentrations. Above 28-milligram-per-liter concentrations, such wells must be properly ventilated to reduce the risk of explosion. One well tested had methane concentrations of 64 milligrams per liter.

“I saw a homeowner light his water on fire,” Jackson notes. “The biggest risk is flammability and explosion.”

Few studies have been done to date on the health risks of chronic exposure to methaneand other gaseous hydrocarbons. (The researchers also found ethane, propane and butane in some of the drinking water wells.)

At the same time, the researchers found no evidence that either the chemicals in fracking fluids or the natural contamination in deep waters were polluting relatively shallow water wells in the vicinity of the deep natural gas wells. That suggests that leaking wells are likely the source of such methane contamination, rather than any migration upward from the deep. “It’s easier to envision a gas well casing that’s leaking, especially with the high pressures, than it is to envision the mass movement of gas or liquids 5,000 feet upwards,” Jackson notes. “I don’t know that it’s impossible but I think it’s unlikely.”

Because of such concerns the U.S. Department of Energy has convened a special task force to improve the safety and environmental impacts of such fracking for natural gas, including how best to dispose of the voluminous wastewater as well as ensuring proper sealing of wells to prevent such groundwater contamination.

“America’s vast natural gas resources can generate many new jobs and provide significant environmental benefits,” noted Secretary of Energy Steven Chu in a prepared statement announcing the panel, “but we need to ensure that we harness these resources safely.” In fact, the panel is charged with providing “recommendations as to actions that can be taken to improve the safety and environmental performance of shale gas extraction processes and other steps to ensure protection of public health and safety,” according to Chu’s memo (pdf) laying out its mission, which must deliver “immediate steps to be taken to improve the safety and environmental performance of fracking” within 90 days of its first meeting.

Fracking is specifically exempted from much federal regulation, such as the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974. Local regulatory requirements may not help: for instance, although the researchers discovered methane contamination at homes within 1,000 meters of active natural gas wells, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection only holds drilling companies responsible for drinking water within 305 meters. “That’s a ninefold increase in area,” Jackson notes. “Who pays for [testing]? Should gas companies be required to do it?”

And it remains to be seen whether natural gas delivers environmental benefits—such as reduced emissions of carbon dioxide when burned—given that it in itself is a potent greenhouse gas if it escapes during drilling or pipeline operations, so-called fugitive emissions. “We are interested in getting pre- and post-drilling samples,” Jackson says of his future research, although he has been threatened with subpoena. “We’d like to get data for fugitive methane emissions as well. This summer we’re going to try and detect methane in the air.”