Der Spiegel: Paris Disagreement – Donald Trump’s Triumph of Stupidity

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other G-7 leaders did all they could to convince Trump to remain part of the Paris Agreement. But he didn’t listen. Instead, he evoked deep-seated nationalism and plunged the West into a conflict deeper than any since World War II. By SPIEGEL Staff

Until the very end, they tried behind closed doors to get him to change his mind. For the umpteenth time, they presented all the arguments — the humanitarian ones, the geopolitical ones and, of course, the economic ones. They listed the advantages for the economy and for American companies. They explained how limited the hardships would be.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel was the last one to speak, according to the secret minutes taken last Friday afternoon in the luxurious conference hotel in the Sicilian town of Taormina — meeting notes that DER SPIEGEL has been given access to. Leaders of the world’s seven most powerful economies were gathered around the table and the issues under discussion were the global economy and sustainable development.

The newly elected French president, Emmanuel Macron, went first. It makes sense that the Frenchman would defend the international treaty that bears the name of France’s capital: The Paris Agreement. “Climate change is real and it affects the poorest countries,” Macron said.

Then, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reminded the U.S. president how successful the fight against the ozone hole had been and how it had been possible to convince industry leaders to reduce emissions of the harmful gas.

Finally, it was Merkel’s turn. Renewable energies, said the chancellor, present significant economic opportunities. “If the world’s largest economic power were to pull out, the field would be left to the Chinese,” she warned. Xi Jinping is clever, she added, and would take advantage of the vacuum it created. Even the Saudis were preparing for the post-oil era, she continued, and saving energy is also a worthwhile goal for the economy for many other reasons, not just because of climate change.

But Donald Trump remained unconvinced. No matter how trenchant the argument presented by the increasingly frustrated group of world leaders, none of them had an effect. “For me,” the U.S. president said, “it’s easier to stay in than step out.” But environmental constraints were costing the American economy jobs, he said. And that was the only thing that mattered. Jobs, jobs, jobs.

At that point, it was clear to the rest of those seated around the table that they had lost him. Resigned, Macron admitted defeat. “Now China leads,” he said.

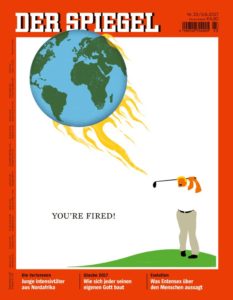

Still, it is likely that none of the G-7 heads of state and government expected the primitive brutality Trump would stoop to when announcing his withdrawal from the international community. Surrounded by sycophants in the Rose Garden at the White House, he didn’t just proclaim his withdrawal from the climate agreement, he sowed the seeds of international conflict. His speech was a break from centuries of Enlightenment and rationality. The president presented his political statement as a nationalist manifesto of the most imbecilic variety. It couldn’t have been any worse.

A Catastrophe for the Climate

His speech was packed with make-believe numbers from controversial or disproven studies. It was hypocritical and dishonest. In Trump’s mind, the climate agreement is an instrument allowing other countries to enrich themselves at the expense of the United States. “I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris,” he said. Trump left no doubt that the well-being of the American economy is the only value he understands. It’s no wonder that the other countries applauded when Washington signed the Paris Agreement, he said. “We don’t want other leaders and other countries laughing at us anymore. And they won’t be. They won’t be.”

Trump’s withdrawal is a catastrophe for the climate. The U.S. is the second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases — behind China — and is now no longer part of global efforts to put a stop to climate change. It’s America against the rest of the world, along with Syria and Nicaragua, the only other countries that haven’t signed the Paris deal.

But the effects on the geopolitical climate are likely to be just as catastrophic. Trump’s speech provided only the most recent proof that discord between the U.S. and Europe is deeper now than at any time since the end of World War II.

Now, the Western community of values is standing in opposition to Donald Trump. The G-7 has become the G-6. The West is divided.

For three-quarters of a century, the U.S. led and protected Europe. Despite all the mistakes and shortcomings exhibited by U.S. foreign policy, from Vietnam to Iraq, America’s claim to leadership of the free world was never seriously questioned.

That is now no longer the case. The U.S. is led by a president who feels more comfortable taking part in a Saudi Arabian sword dance than he does among his NATO allies. And the estrangement has accelerated in recent days. First came his blustering at the NATO summit in Brussels, then the disagreement over the climate deal in Sicily followed by Merkel’s speech in Bavaria, in which she called into question America’s reliability as a partner for Europe. A short time later, Trump took to Twitter to declare a trade war — and now, he has withdrawn the United States from international efforts to combat climate change.

A Downward Pointing Learning Curve

Many had thought that Trump could be controlled once he entered the White House, that the office of the presidency would bring him to reason. Berlin had placed its hopes in the moderating influence of his advisers and that there would be a sharp learning curve. Now that Trump has actually lived up to his threat to leave the climate deal, it is clear that if such a learning curve exists, it points downward.

The chancellor was long reluctant to make the rift visible. For Merkel, who grew up in communist East Germany, the alliance with the U.S. was always more than political calculation, it reflected her deepest political convictions. Now, she has — to a certain extent, at least — terminated the trans-Atlantic friendship with Trump’s America.

In doing so, the German chancellor has become Trump’s adversary on the international stage. And Merkel has accepted the challenge when it comes to trade policy and the quarrel over NATO finances. Now, she has done so as well on an issue that is near and dear to her heart: combating climate change.

Merkel’s aim is that of creating an alliance against Trump. If she can’t convince the U.S. president, her approach will be that of trying to isolate him. In Taormina, it was six countries against one. Should Trump not reverse course, she is hoping that the G-20 in Hamburg in July will end 19:1. Whether she will be successful is unclear.

Trump has identified Germany as his primary adversary. Since his inauguration in January, he has criticized no country — with the exception of North Korea and Iran — as vehemently as he has Germany. The country is “bad, very bad,” he said in Brussels last week. Behind closed doors at the NATO summit, Trump went after Germany, saying there were large and prosperous countries that were not living up to their alliance obligations.

And he wants to break Germany’s economic power. The trade deficit with Germany, he recently tweeted, is “very bad for U.S. This will change.”

An Extreme Test

Merkel’s verdict following Trump’s visit to Europe could hardly be worse. There has never been an open break with America since the end of World War II; the alienation between Germany and the U.S. has never been so large as it is today. When Merkel’s predecessor, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, refused to provide German backing for George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, his rebuff was limited to just one single issue. It was an extreme test of the trans-Atlantic relationship, to be sure, but in contrast to today, it was not a quarrel that called into question commonly held values like free trade, minority rights, press freedoms, the rule of law — and climate policies.

To truly understand the consequences of Trump’s decision, it is important to remember what climate change means for humanity — what is hidden behind the temperature curves and emission-reduction targets.

Climate change means that millions are threatened with starvation because rain has stopped falling in some regions of the planet. It means that sea levels are rising and islands and coastal zones are flooding. It means the melting of the ice caps, more powerful storms, heatwaves, water shortages and deadly epidemics. All of that leads to conflicts over increasingly limited resources, to flight and to migration.

In the U.S., too, there were plenty of voices warning the president of the consequences of his decision, Trump’s daughter Ivanka and her husband Jared Kushner among them. Others included cabinet members like Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Energy Rick Perry, along with pretty much the country’s entire business elite.

Companies from Exxon and Shell to Google, Apple and Amazon to Wal-Mart and PepsiCo all appealed to Trump to not isolate the U.S. on climate policy. They are worried about international competitive disadvantages in a world heading toward green energy, whether the U.S. is along for the ride or not. Google, Microsoft and Apple have long since begun drawing their energy from renewable sources, with the ultimate goal of complete freedom from fossil fuels. Wind and solar farms are booming in the U.S. — and hardly an investor can be found anymore for coal mining.

A long list of U.S. states, led by California, have charted courses that are in direct opposition to Trump’s climate policy. According to a survey conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, almost three-quarters of Americans are opposed to withdrawing from the Paris Agreement.

The Absurdity of Trump’s Histrionics

On the other side are right-wing nationalists such as Trump’s chief strategist Stephen Bannon, who deny climate change primarily because fighting it requires international cooperation. Powerful Republicans have criticized the climate deal with the most specious of all arguments. The U.S., they say, would be faced with legal consequences were it to miss or lower its climate targets.

Yet international agreement on the Paris accord was only possible because it contains no punitive tools at all. The only thing signatories must do is report every five years how much progress they have made toward achieving their self-identified climate protection measures.

Therein lies the absurdity of Trump’s histrionics. Nothing would have been easier for the U.S. than to take part pro forma in United Nations climate-related negotiations while completely ignoring climate protection measures at home — which Trump has been doing anyway since his election.

In late March, for example, he signed an executive order to unwind part of Barack Obama’s legacy, the Clean Power Plan. Among other measures, the plan called for the closure of aging coal-fired power plants, the reduction of methane emissions produced by oil and natural gas drilling, and stricter rules governing fuel efficiency in new vehicles. Without these measures, Obama’s goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by up to 28 percent by 2025, in comparison to 2005, will hardly be achievable. But Trump is also planning to head in the opposite direction. To make the U.S. less dependent on energy imports, he wants to return to coal, one of the dirtiest energy sources in existence — even though energy independence was largely achieved years ago thanks to cheap, less environmentally damaging natural gas.

German and European efforts will now focus on keeping the other agreement signatories on board, which Berlin has already been working on for several weeks now. Because of the now-visible effects of climate change and the falling prices for renewable energies, German officials believe that the path laid forward by Paris is irreversible.

Berlin officials say that EU member states are eager to move away from fossil fuels, as are China and India. Even emissaries from Russia and Saudi Arabia, countries whose governments aren’t generally considered to be enthusiastic promoters of renewable energy sources, have indicated to the Germans that “Paris will be complied with.” On Thursday in Berlin, Merkel and Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang demonstratively reaffirmed their support for the Paris Agreement. Keqiang even spoke of “green growth.”

China and India are likely to not just meet, but exceed their climate targets. China has been reducing its coal consumption for the last three years and plans for over 100 new coal-fired power plants have been scrapped. India, too, is abstaining from the construction of new coal-fired plants and will likely meet its goal of generating 40 percent of its electricity from non-fossil fuels by 2022, eight years earlier than planned. Both countries invest in solar and wind energy and in both, electricity from renewable sources is often cheaper than coal power.

Isolating the American President

The problem is that all of that still won’t be enough to limit global warming to significantly below 2 degrees Celsius, as called for in the Paris deal. Much more commitment, much more decisiveness is necessary, particularly in countries that can afford it. German, for example, is almost certain to fall short of its target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40 percent by 2020 relative to 1990.

In Taormina, Chancellor Merkel did all she could to isolate the American president. In the summit’s closing declaration, she wanted to specifically mention the conflict between the U.S. and its allies over the climate pact. Normally, such documents tend to remain silent on such differences.

At the G-20 meeting in Hamburg, Merkel plans to stay the course. She hopes that all other countries at the meeting will stand up to the United States. Even if Saudi Arabia ends up supporting its ally Trump, the end result would still be 18:2, which doesn’t look much better from the perspective of Washington.

Merkel, in any case, is doing all she can to ramp up the pressure on Trump. “The times in which we could completely rely on others are over to a certain extent,” she said in her beer tent speech last Sunday.

It shouldn’t be underestimated just how bitter it must have been for her to utter this sentence, and how deep her disappointment. Merkel, who grew up in the Soviet sphere of influence, never had much understanding for the anti-Americanism often found in western Germany. U.S. dependability is partly to thank for Eastern Europe’s post-1989 freedom.

Merkel has shown a surprising amount of passion for the trans-Atlantic relationship over the years. She came perilously close to openly supporting the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq and enjoyed a personal friendship with George W. Bush, despite the fact that most Germans had little sympathy for the U.S. president. Later, Merkel’s response to the NSA’s surveillance of her mobile phone was largely stoic and she also didn’t react when Trump called her refugee policies “insane.”

As such, Merkel’s comments last Sunday about her loss of trust in America were eye-opening. It was a completely new tone and Merkel knew that it would generate attention. Indeed, that’s what she wanted.

A Clear Message to the U.S.

Her sentence immediately circled the globe and was seen among Trump opponents as proof that the most powerful woman in Europe had lost hope that Trump could be brought to reason.

Prior to speeches to her party, such as the one held last Sunday, she always gets a manuscript from Christian Democratic Union (CDU) headquarters in Berlin, but she herself writes the most decisive passages. The comment about Europe’s allies was a clear message to the U.S., but it was also meant for a domestic audience. Her speech marked the launch of her re-election campaign.

Merkel knows that her campaign adversaries from the center-left Social Democrats (SPD) intend to make foreign policy an issue in the election. After all, it has a long history of doing so. Willy Brandt did so well in 1969 and 1972 in part because he called into question the Cold War course that had been charted to that point. Gerhard Schröder managed to win in 2002 in part because of his vociferous rejection of German involvement in the coming Iraq War.

Last Monday, German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel, a senior SPD member, took advantage of a roundtable discussion on migration in the Foreign Ministry to lay into Trump. The largest challenges we currently face, such as climate change, he said, have been made “even larger by the new U.S. isolationism.” Those who don’t resist such a political course, Gabriel continued, “make themselves complicit.” It was a clear shot at the chancellor.

But her speech last Sunday shielded Merkel from possible accusations of abetting Trump, though she nevertheless wants to keep the dialogue going with Washington. Speaking to conservative lawmakers in Berlin on Tuesday, she said that the trans-Atlantic relationship continues to be of “exceptional importance.” Nevertheless, she added, differences should not be swept under the rug.

Merkel realized early on just how difficult it would be to work with the new U.S. president, partly because she watched videos of some of his pre-inauguration appearances. Speaking to CDU leaders in December, she said that Trump was extremely serious about his slogan “America First.”

The chancellor’s image of Trump has shifted since then, but not for the better. The first contacts with the new government in Washington were sobering. When Christoph Heusgen, her foreign policy adviser, met for the first time with Michael Flynn, who was soon to become Trump’s short-lived national security adviser, he was shocked by his American counterpart’s lack of knowledge.

Shattered Hopes

But there were still grounds for optimism. Early on, Merkel thought that the new U.S. government’s naiveite might mean that Trump could be influenced. She was hoping to play the role of educator, an approach that initially looked like it might be successful. In a telephone conversation in January, Merkel explained to Trump the situation in Ukraine. She had the impression that he had never before seriously considered the issue and she was able to convince him not to lift the sanctions that had been placed on Russia.

The new president has likewise thus far refrained from moving the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. He has also left the Iran deal alone and revised initial statements in which he had said that NATO was “obsolete.” In the Chancellery, there was hope that Trump could in fact become something like a second-coming of Ronald Reagan.

Those hopes have now been shattered. Because Trump has had difficulty fulfilling many of his campaign promises, he has become even more intransigent. Merkel watched in annoyance as Trump did all he could in Saudi Arabia to avoid upsetting his hosts only to come to the NATO summit and cast public aspersions at his allies. The bad thing about Trump is not that he criticizes partners, says a confidante of Angela Merkel’s, but that in contrast to his predecessors, he calls the entire international order into question.

At one point, Merkel took Trump aside in Sicily to speak with him privately about climate protection and the president told her that he would prefer to delay his decision on the Paris Agreement until after the G-20 in July. You can postpone everything, Merkel replied, but it’s not helpful. She urged that he make a decision prior to the Hamburg summit.

He has now done so.

To the degree that one can make such a claim, Trump has a rather functional view of Merkel. He wants her to increase defense spending and to reduce Germany’s trade surplus with the U.S., even if it is a political impossibility. And he wants Merkel to force other European leaders to do the same, even though Merkel doesn’t possess the power to do so.

In Trump’s world, there are no allies and no mature relationships, just self-interested countries with short-term interests. History means nothing to Trump; as a hard-nosed real-estate magnate, he is only interested in immediate gains. He cares little for long-term relationships.

Two close advisers to the president contributed a piece to the Wall Street Journal this week that can be seen as something like a “Trump Doctrine.” “The world is not a ‘global community,'” wrote Gary Cohn and Herbert Raymond McMaster, Trump’s economic and security advisers. The subtext is clear: The global order, which the United States helped build, belongs to the past. There are no alliances anymore, just individual interests — no allies, just competitors. It was a clear signal to America’s erstwhile Western allies that they can no longer rely on the United States as a partner.

In: derspiegel