Our pick from Peru.

In retrospective, NN shouldn’t work. On the surface, this is a bleak, inexpressive approach to death and memory, a film as cold its subject. Do we really need to be reminded of the burden of loss and grief? Isn´t it better to try a resignification of the value of memory instead of pushing the same loss-depression scheme? Despite all this, I still was deeply moved by Héctor Gálvez´ second film, a powerful and unique study of memory, death and those who take care of them. In this film, most thigs remain unsaid and most emotions have to be deciphered through the limited symbolism in the screen. It´s worth it.

The story is pretty easy to follow. A team of forensic experts, lead by Fidel Carranza, begin an exhumation of clandestine graves in the middle of the Andes. The victims were murdered during the armed conflict in Peru. Most of them were Quichua-speaking farmers without a clear connection to either party involved. In one exhumation, eight bodies are found, although only seven were expected. The unknown body carries a small photograph in a pocket of its jacket: it´s the picture of a young girl. A much older woman comes to reclaim the body, despite denying that the picture is hers. As ironic as possible, two pieces that should match in the puzzle just don´t. A corpse has no face and a face has no corpse.

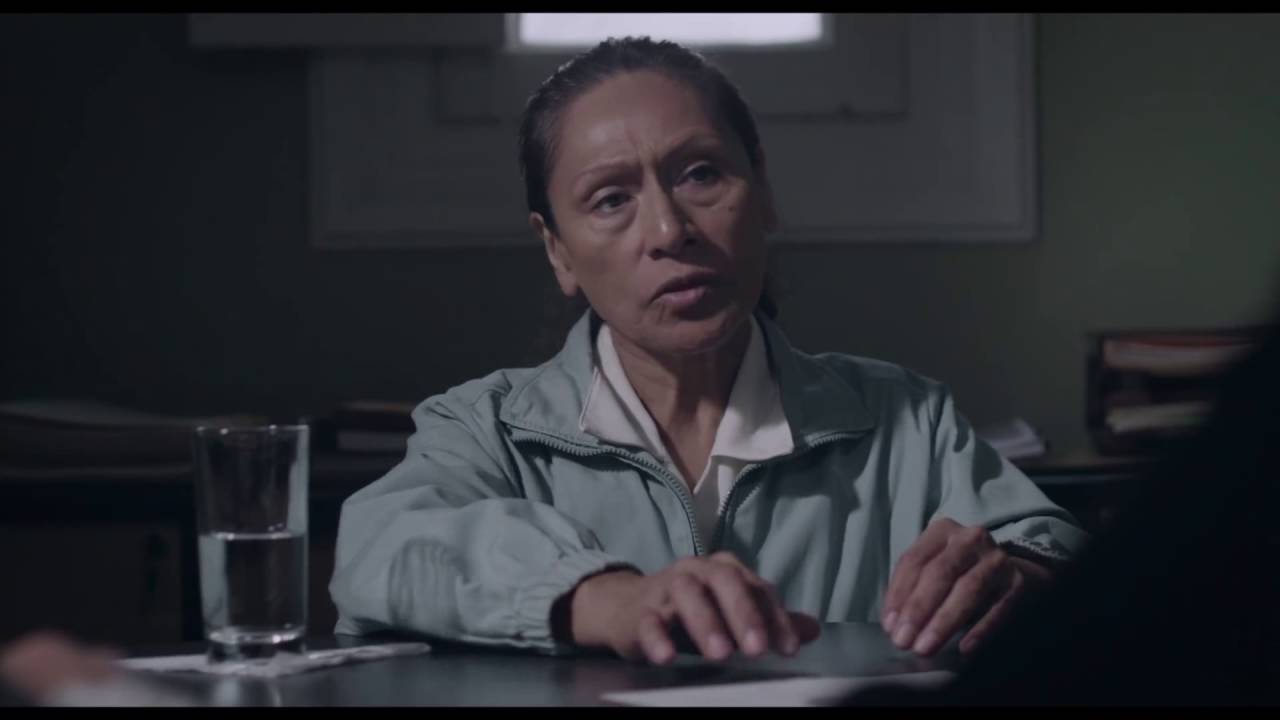

This story relies on a contradiction. Is the same contradictory relationship that arises between Fidel and the widow, Graciela, deeply convinced of her husband´s identity. A very depressed Fidel tries to find a purpose and Graciela has found one in a huntch, which is extremely uncertain. It is always interesting to pay attention to those unexpected, almost impossible relationships described in movies, those based solely on arbitrary reasons, too painful to be evoked. In this case, Fidel and Graciela are tangled by tragedy. Fidel, silent, driven by melancholy, struggles to keep up with a job so surrounded by pain and loss. A sense of dreadd is perpetually living inside him. Graciela is her direct opposite: a woman who, despite her loss, decides to resist. She places all her hopes in a indulgent search, even though this leads others to reject her.

Between Fidel and Graciela lies a victim-protector dinamic, tailored by promises, silences, even some sore of trust. A mother-son relationship, or its lookalike. The film doesn´nt circle back to it. It doesn’t have to. In the end, this is a fortuitous encounter, and it has to stay as such: brief, conflictive. The film decides to juxtapose both storylines as it progresses. The more the mistery is unfolded, the more unteable their vincle gets. Fidel is desperate to give an answer to Graciela, which will further justify his emotional involvement with the case and his constant desilussion with his job.

We have to pay close attention to detail, specially the small ones. The camera fixates itself with the abandoned: abandoned items, clothes, bodies. Galvez carefully chooses every piece that deserves a close-up. The tools used by the forensics. The clothes and other belongings of the dead, almost mummified, covered by dust. The bodies, as changeable pieces in a much bigger puzzle, as nameless victims. Each body part: a finger, a knee, a part of the skull. The film makes them the protagonists: gets them to tell their story. Of course, this is a different approach to death in cinema -the forensic one- which may be challenging to the audience. As Graciela and the team, Galvez seems to be obsessed by the bodies and their identities, so he keeps filming them, almost giving them life.

The majority of the public will probably try to understand this approach, but will eventually fail at it. This is because the longing for the disappeared, an experience defined by tragedy and repression, is itself an anomaly: something that is never supposed to happen. Few know what is like to love those who are lost. It means to spend days wandering down the desert, like the women from Atacama, Chile do. It means to scrabble in the earth, trying to get something out of an apparently futile endeavor. For people who search and never start searching, for those who have lost almost anything in the search, a bone, a piece of cloth means everything. It is paradoxical in its nature: any detail is sufficient to tell a story, but no number of details pieced together will be close to equal to entire body.

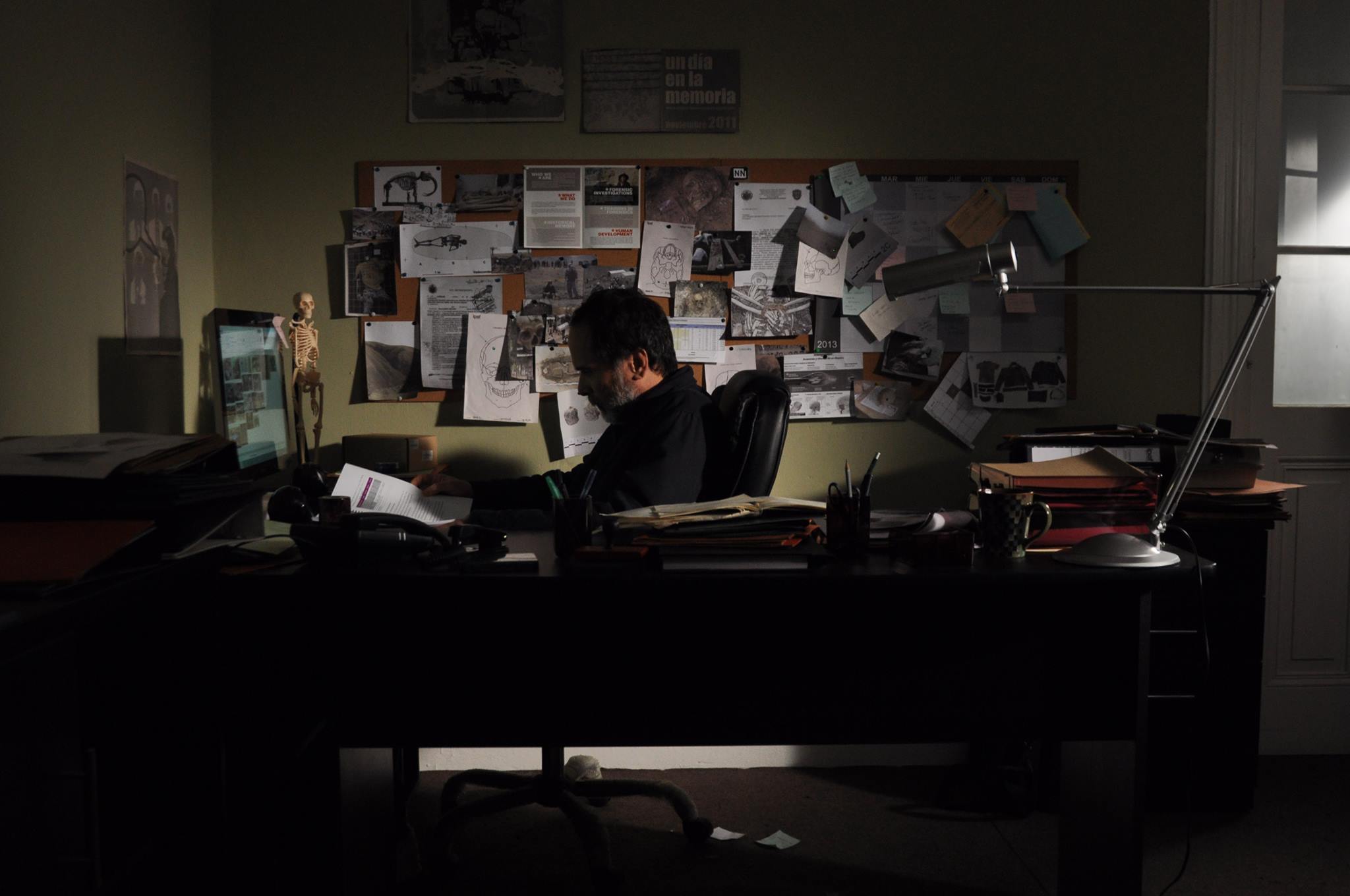

Not every detail is inert. For Galvez, faces also matter. Like empty canvasses waiting to be painted, faces are capable to express more than any piece of dialogue, capable of confronting the viewer with deeply awkward but needed emotions. Like bodies, every face has numerous stories to tell: Paul Vega´s melancholic, puzzled look, wandering around the morgue; the weak, but still lively hope in Antonieta Pari´s face, a tired look that stays with the audience. The preference for faces is not incidental: in the end, the film cares for the lost faces, those forgotten, looking for a body, a clear sense of identity, that can give them meaning.

Gálvez style allows contemplation. I said it before: it’s a dry, lazy still, one that takes the story little by little. Most shots are symmetric and rigid, filtered by tones of blue, like the humid walls of hospitals and morgues. This is a film cut by scalpel, with a precise, if concise management of emotions. It works. Blue is both nostalgic and lugubrious. Blue is emotional, but not too emotional. Blue captures all.

To think about these emotions takes me back to Fidel. How doubt arises in him. Graciela insists in knowing that body. Evidence is no on her side. Is it legitimate to have a close relationship with the victims, as Fidel is beginning to do? What are the limits of empathy? How can we manipulate the truth? The dilemma stays with us. Unanswered questions only have two options: uncertainty or lies. Fidel, governed by guilt, can choose between the happiness of a poor widow –by sacrificing his identity- or to follow his rigid principles, that have taken him nowhere.

To give the dead a face that doesn’t belong to them. It isn´t easy.

NN also works as a raw critique of a system that doesn’t seem to value the dead. Fidel´s world is one of cold-hearted bureaucracy, apathy, disinterest. The dead don’t matter. Gálvez also films them that way: bodies hidden in boxes, waiting to be knows; bodyless caskets, and nobody visiting them.

This dilemma continues until the end. In NN´s closing chapter, we watch one of the most disheartened scenes in contemporary Peruvian film. Fidel, trying to cope with his emotions, decides to face the truth: he goes to the Ministry’s attic, the place that was arbitrarily chosen to serve as deposit for the unidentified bodies. He watches in despair. Boxes pile up. Broken bones come out of them. Different bodies are confused between each other. Just disarray. Fidel, as Sisyphus, finds himself in the absurd, in a system devoted to destroy what it wanted to accomplish. Those bodies will never rest.

Fidel´s sorrowful face can be understood in diverse ways. He has a futile job. He cannot comfort the ill. He is not even the man he wanted to be. All these thoughts seem to be as the core of Fidel´s moral judgment. He is forced to choose the alternative he despises. He is forced to forget the truth.

In the end, once the body is buried, Graciela is finally appeased.

Everybody mourns as they choose.